My title alludes to some notes for the layperson that I rediscovered recently. I have reviewed and edited them, and they are below, in the following sections (linked to by the titles after the three main bullets; other links are to Wikipedia).

- “Quasicrystals,” based on an email of mine sent to a group of alumni of St John’s College on October 8, 2011. This was my contribution to a thread in which somebody said that

- Dan Schechtman (whom she called Danny) was a worthy recipient of that year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of quasicrystals, but

- John Cahn deserved credit, even the prize itself, as the real discoverer.

My wife and I had recently moved to Istanbul, and the Istanbul Model Theory Seminar had just got going. The Nobel Prize and quasicrystals had been mentioned there too.

- “Free Groups,” based on an email of October 10, 2011. I tried to describe free groups to somebody who expressed interest, but who also called himself the world’s worst mathematician.

- “Topology” – a draft of an attempt to describe that subject. In graduate school, I got excited about the definition of a topological space when I first encountered it. Here I try to motivate the definition by abstracting from the properties of the Cartesian plane as a metric space. I give the example of the Zariski topology on the same plane. I start to talk about the topology derived from the Gromov–Hausdorff metric on the space of groups with n generators, but then I stop.

Vegetable plot in Yeniköy (where Cavafy lived a while), Istanbul, Saturday, September 28, 2024

Before I get to all of that, there is something I did not take up in my last post, “Motivated Reasoning in the Cyropaedia of Xenophon,” because it was already long. Cyrus the Great is like a mathematician.

The word “front” can be used as a verb with the meaning of “confront.” The Merriam-Webster dictionary illustrates this meaning with the passage of Walden where Thoreau writes,

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.

Cyrus and the mathematician front an unfiltered reality. The filter that they avoid is fashion, understood as something that doesn’t last.

In summoning his Persian nephew to meet an embassy from India, Cyaxares of Media sends along a garment suitable for the occasion: a most beautiful stole (στολή καλλίστη). Cyrus disdains to put it on. He makes haste with his men as they are. His uncle is annoyed, until Cyrus placates him by asking (II.iv.6),

Should I have done you more honour if I had put on a purple robe, and bracelets for my arms, and a necklace about my neck, and so presented myself at your call after long delay? Or as now, when to show you respect I obey you with this despatch and bring you so large and fine a force, although I wear no ornament but the dust and sweat of speed, and make no display unless it be to show you these men who are as obedient to you as I am myself?

If mathematics follows a fashion, it has done this since the Greeks. There would seem to remain only historical interest in what Ptolemy did in astronomy, and Aristotle before him in biology and physics; however, the work of Euclid, Archimedes, and Apollonius is of a piece with the mathematics of today.

Having been reading Euclid’s Elements with a diverse group since the winter of 2023, and having only in recent weeks reached the arithmetic of Book VII, I can suggest that Euclid provides new ways of thinking about numbers, if we can suppress the conviction that we already know what numbers are.

I wrote something about that in “The Geometry of Numbers in Euclid” (January, 2017). I observed that addition of Euclid’s magnitudes was continuous, although one might try to imagine a geometry in which this failed. I pursue this thought for a moment now.

Unless restricted to ω, addition of positive ordinals is not commutative. Take for example the countable ordinal ωω, which is closed under multiplication as well as addition. As a multiplicative semigroup, this ordinal acts from the right, by multiplication, on itself as a set. As being

- a set so acted on,

- an additive semigroup, and

- a linear order,

the ordinal embeds in itself under left multiplication by any positive element, particularly an element that exceeds 1. Taking the direct limit of an infinite system of such embeddings, we obtain a dense linear order and semigroup, still acted on as a set by ωω. Such a structure has some resemblance to Euclid’s magnitudes, although the addition is not commutative. It would be of independent interest to know whether, or how, the first-order theory of the limit structure depends on the system of embeddings that yields it. For all I know at the moment, the theory may be as difficult to understand as that of a free group.

Menswear writer Derek Guy tweeted recently (September 29, 2024),

Ultimately, I think people should be wary of overly simplistic rules, such as “avoid logos.” These are often crutches people rely on when they don’t yet have a sense of taste. Instead, think of aesthetics as cultural language and appreciate the wide world of culture.

Perhaps “logos” here should be spelled “logoes,” to avoid confusion with λόγος; however, one should certainly be wary of a rule to avoid this kind of logos too. Above a quotation of Guy’s tweet, I added,

“Be wary of overly simplistic rules” – itself a good rule for life, seen (I believe) in The Education of Cyrus.

I blogged about Xenophon’s work recently (along with related things).

Make up your own mind, says Cyrus, case by case.

Cyrus avoids living by rule, but deals with each situation as it arises. There is a simple example in how he has his army approach Babylon. The first time, he wants to get close. Next time, he doesn’t, “for marching up to and marching by are not the same thing” (οὐ γὰρ τὸ αὐτό ἐστι προσάγειν τε καὶ παράγειν, V.iv.44).

Cyrus has been advised by a defector from the Assyrians that he may win another defector on the other side of the city. This is because, while he was still only the son of the ruler, the man who now rules Babylon

- killed the son of Gobryas for being the better hunter (IV.vi.3 & 4),

- had Gadatas himself castrated for being praised in his looks by a concubine (V.ii.28).

Although Gobryas warns against it, Cyrus himself plans to march right up to Babylon, since, as he tells his new ally (V.ii.31–37),

- if we avoid the Assyrians, they will think we fear them;

- if we approach them, they will remember how we have already defeated them;

- the larger their numbers, the greater their panic at the thought of that defeat and our approach;

- if victory is won by good fighting, we can be confident;

- your own men are the better for being with ours;

- the enemy can always find us if they want to.

Outside the walls of Babylon, Cyrus has Gobryas send in the message that he will fight on the king’s side, if the king will actually come out to do it. The king replies,

- I should have killed you, in addition to your son;

- I am too busy to fight just now, come back in a month.

Cyrus and Gobryas proceed beyond the city and gain Gadatas as an ally. On the way back, Cyrus wants to avoid Babylon, and Gadatas is astonished, since Cyrus’s army is even larger now. However, it would be a lot of work to protect the long train of Cyrus’s army as it passed by the walls of Babylon. If the enemy did come out to fight, they should have to put some distance between themselves and the protection of their walls (V.iv.43–49).

Gadatas has thought Cyrus to follow a rule, “Always front the enemy.” He does not. He fronts the actual situation.

Science aims to do that too, but on a foundation of what R. G. Collingwood (1889–1943) calls absolute presuppositions. I have written a fair amount about these, as for example in “Nature” (October, 2021), where I quote Simon Blackburn as saying that absolute presuppositions are

something like the paradigms of Thomas Kuhn: the resources for thought and the devices for structuring it that, in a particular period of time, form the framework within which ordinary investigation proceeds.

In “What It Takes” (May, 2018), I quote Blackburn as likening absolute presuppositions to fashions. In doing this, he says we cannot recognize our own absolute presuppositions. I think he is mistaken here. I might add that we can recognize our own fashions too, at least if we are like Derek Guy. Collingwood himself suggests the analogy with fashion in An Autobiography (1939):

Ideals of personal conduct are just as impermanent as ideals of social organization. Not only that, but what is meant by calling them ideals is subject to the same change …

In metaphysics the corresponding analysis was easy to one who had been addicted from childhood to the history of science. I could not but see, for example, when Einstein set philosophers talking about relativity, that philosophers’ convictions about the eternity of problems or conceptions were as baseless as a young girl’s conviction that this year’s hats are the only ones that could ever have been worn by a sane woman. One heard them maintaining the ‘axiomatic’ or ‘self-evident’ character of doctrines about matter, motion, and so forth which had first been propounded by very adventurous thinkers, at risk of their own liberty and life, three or four hundred years ago, and had become part of every educated European’s beliefs only after long and fanatical propaganda in the eighteenth century.

It may have been needed for the work of Galileo (1564–1642), but I am not aware that any fanatical propaganda was needed to promote Descartes’s Geometry of 1637. Descartes has changed the way we do mathematics, but only by showing that when we manipulate polynomial equations of arbitrarily high degree, we are only doing things that can be understood geometrically. Pappus of Alexandria was aware of the possibility in ancient times, as Descartes points out. In short, our mathematics is somehow still the same.

As for Thomas Kuhn (1922–96), he has come up in other posts, such as “Rethinking” (July, 2024), but again only in quotations about him, since I have not spent much time with his own work. Here is another quote though, from Gary Stix, “A Q&A with Ian Hacking on Thomas Kuhn’s Legacy as ‘The Paradigm Shift’ Turns 50” (Scientific American, April 27, 2012):

Kuhn advanced the idea that scientists in a particular field share an existing set of practices – a paradigm – that allows them to labor away using common methods on like research problems – what he labeled “normal science.” Eventually, experimental anomalies accrue that foment revolutionary change – the ballyhooed paradigm shift that overturns the existing order and ushers in a new era that may differ radically from the old.

That “incommensurability,” as Kuhn termed it, held that after a true revolution, an existing body of theory bears no relationship to the new theoretical framework, the opposite of “standing on the shoulders of giants.” In other words, the concept of mass in the new world of E = mc2 differs fundamentally from the same designation in the old classical mechanics of F = ma.

One might still say that Einstein, Galileo, and Aristotle are all studying the same world. I could ask then, for example, whether this is the same world studied by William Blake, one of whose “Proverbs of Hell” reads,

A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees.

In any case, while I think it makes perfect sense that the freshman of my department should read Euclid as an introduction to their study of mathematics, it is hard to imagine students of physics today starting out with Aristotle’s Physics.

My thought would seem to be corroborated in four recent tweets of Dave Richeson (September 27, 2024):

I was reminded again of the difference between math and the sciences. My dad received an award yesterday from the U of Rochester Medical School alumni association, which was wonderful! At the award dinner, one speaker mentioned a discussion with Seymour Schwartz, | another U of R professor, about celebrating the 50th anniversary of his seminal text Principles of Surgery (1969). Schwartz commented that the problem with focusing on the first edition is that almost everything in it was wrong! (He gave an example of a very common surgery for a | condition now treated with antibiotics.) During his speech, my dad referenced the Schwartz comment and said he tells his cardiology students that 50% of what they will learn is wrong. The problem is, we don’t know which 50%. In contrast, Euclid’s Elements, written two and a | half millennia ago, is still correct!

There was the inevitable objection, this one by Daniel Litt:

I think it holds up well, but this is a bit of an overstatement. E.g. there’s a gap in the proof of Book I, Proposition 1!

Richeson responded,

Ha! When I wrote that tweet, I knew someone would reply this way! I’m surprised it took 18 hours. 🤣🤣 But seriously, the shortcomings of Euclid’s Elements seem very different than scientific errors.

I tried to support that as follows.

Indeed. I’m not sure what the shortcomings of the Elements would be by the author’s own standards.

Example 1.2.3 (pp. 37–8) of Baldwin’s book here is of basic errors (not just gaps) in Spivak’s Calculus (a book I continue to appreciate nonetheless)

The example from John Baldwin’s book, Model Theory and the Philosophy of Mathematical Practice, is the one involving “Pierce’s Paradox” that I mentioned in “Anthropology of Mathematics.” Perhaps the “gap” that Litt refers to is Euclid’s supposed failure to assert that two triangles sharing the same segment as a radius must intersect one another. I say, let it be understood as asserted by Proposition I.1 itself, just as the “Side-Angle-Side” rule of triangle congruence is asserted by Proposition I.4.

Quasicrystals

As noted above, this is based on an email of October 8, 2011. It is said of Dan Schechtman,

when he found the quasicrystals, he really didn’t know that what he had found was interesting. It was John Cahn who really discovered quasicrystals.

I think this is saying that to discover something is not to hold it in your hand, but to know what it means. Makes sense to me.

Yesterday afternoon was the first meeting of the Istanbul Model Theory Seminar. Before we got things going, one member was telling us excitedly about this work on quasicrystals. I think his main point was that the mathematics preceded the chemistry; the theoretical existence of these things was known before their physical existence was discovered. When he named Shechtman as the discover of the physical version, I said I had learned that there was more to the story.

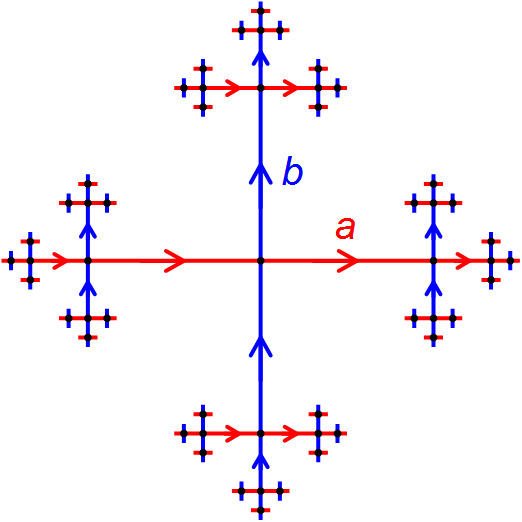

By the way, the aim of the Istanbul Model Theory Seminar, for now, is to study Zlil Sela’s solution to (one of) Tarski’s problems on free groups. The top of the Wikipedia article has a nice “crystalline” diagram of a free group.

Apparently it took six decades to solve these Tarski Problems – which are however easy to state if you know the meaning of the terminology (which I know most of you all don’t). The main problem (to my mind) is:

Are any two nonabelian finitely generated free groups elementarily equivalent? That is, can there be two such groups that are mathematically different (that is, non-isomorphic), although they are indistinguishable by first-order logic?

My own doctoral work dealt with the same question for a different class of structures (function-fields of elliptic curves, rather than free groups). I could not get very far.

At a model theory meeting in Istanbul in August, a student of Sela named Chloé Perin gave a nice series of lectures on the background of Sela’s solution of Tarski’s problem. This gave me the idea of learning more, and apparently the other Istanbul model theorists have agreed.

Free Groups

This is based on an email of mine sent on October 10, 2011.

The Wikipedia article on free groups perhaps does not give the clearest possible account.

A free group is precisely a “free object” in the “category” of groups. There is no need to define all of the technical terms here; the point is that “freeness” is a general concept in mathematics. Even in high school algebra, one encounters freeness, although it is not named as such.

The set of all polynomials in a given variable, say X, with coefficients from (say) the rational numbers, is a free object. Why? You create such a polynomial by combining rational numbers, and the variable X, using addition, subtraction, and multiplication. You can repeat these operations as many times as you like: any two polynomials can be added or multiplied together, or one can be subtracted from the other, to create a new polynomial.

There are some rules: For example, if f, g, and h are polynomials, then (f + g) + h and f + (g + h) are counted as the same polynomial. The rules are just the rules that apply when rational numbers themselves are combined. But that’s it. If two seemingly different polynomials cannot be shown to be equal by means of the standard rules of arithmetic, then they are different polynomials. Therefore the set of polynomials (in X over the rationals) is free. (To be precise, it is a free object, on the single generator X, in the category of algebras over the rationals. Polynomials in two variables would be free objects with two generators, and so on.)

Note that we did not use division in constructing polynomials. Division is not a “total” operation: you cannot divide by 0. In the rationals, you can divide by every number besides 0, and therefore the rationals compose a “field”; but the category of fields does not have free objects, and this has to do with the impossibility of division by 0.

In our polynomials, we could replace the variable X with, say, a symbol a, which is treated as the square root of 2. We would then no longer have a free object, since a2 (that is, aa) would be treated as 2, even though there is no arithmetical rule that requires this: it is just our external requirement.

Back to groups. These have the operations of multiplication and division only. They contain 1 (one), but not 0 (zero); and there is nothing that you cannot divide by. For example, with the positive rational numbers – those rational numbers that are greater than 0 – we can multiply and divide freely, and 1 is among these numbers. Therefore the positive rational numbers compose a group.

The positive rationals are more precisely an “Abelian” group, because here

xy = yx.

(Apparently Abel studied some groups that happened to have this property, so they took his name. Some people just say “commutative.”)

It is potentially misleading to say that groups contain 1 but not 0. The point is that all groups have an element such that multiplying by it and dividing by it have no effect, and this element is often called “one.” Also, in a group, there is no element that cannot be divided by. But all rational numbers – positive, negative, and 0 – compose a group, an Abelian group, in which “multiplication” is addition, “one” is 0, and “division” is subtraction. In this group, there is nothing special about the number 1.

Groups need not be Abelian. The archetypical group consists of the reversible ways of rearranging some things – for example, rearranging the cards in three-card monte (here there are six rearrangements). Multiplying two rearrangements means just doing one and then the other. The order matters. Dividing by a rearrangement means reversing that rearrangement. The rearrangement called “one” is doing nothing at all.

We can create a group out of symbols, such as X and Y. We need also the symbol 1, since every group contains a “one.” Again, multiplying and dividing by 1 have no effect; also, dividing by X means multiplying by what we may call X −1. Our group then consists of 1, and also strings of the symbols X, Y, X −1, Y −1, subject to the provision that X and X −1 are never adjacent, and neither are Y and Y −1 (otherwise they cancel each other and are erased). Multiplying two strings means writing one and then the other, and then performing any resulting cancellations. Thus

XXYXY −1 times YX −1Y equals XXYY, or X2Y2.

We can consider X as X1, and Y as Y1. Then dividing by a string means multiplying by the same string in reverse order, with exponents interchanged:

-

X divided by Y −1X equals X times X −1Y, or Y.

-

X divided by XY −1 equals X times YX −1, or XYX −1

(with no cancellation in the latter example).

The group that we have just created is the free group on the two generators X and Y. The free group on a single generator X can be understood as consisting of strings of any of three forms

X −1X −1⋯X −1, 1, XX⋯X;

alternatively, it consists of the powers Xn, where n is an integer. This group is an infinite cyclic group. A finite cyclic group also consists of elements an for some a, but then an = 1 for some nonzero n. This condition is not imposed by the laws of groups, so the finite cyclic group is not free.

The free group on one generator is abelian; all other free groups are not. There are free abelian groups, that is, free objects in the category of abelian groups; but these are something else. An infinite cyclic group is free in two categories: the category of groups, and the category of abelian groups; but no other group has this property except the group with no generators, consisting of 1 only.

Tarski’s Problem is to determine whether, by first-order logic, you can tell the difference between a free group on two generators and a free group on any greater number of generators. It is now a theorem, proved by Sela and by Myasnikov and Kharlampovich, that you cannot. It is difficult work, and I don’t know how far our Istanbul seminar can get with it.

But my own ph.d. research began with the question (raised by my advisor) of whether there was a logical difference between the polynomials in one and two variables (with coefficients from the complex numbers). The answer turned out to be known, and to be Yes: it was an easy consequence of the “Tsen–Lang Theorem.” I ultimately turned to Tarski’s Problem, let us say, as applied to function fields of elliptic curves. These matters are part of “field theory” in the broadest sense. Group theory is a wilder subject, I think; intuitions here seem to come less naturally, at least to me; but the logical result on free groups seems most impressive, and I like to imagine that it might even help to improve my ph.d. results.

Topology

The following is my attempt to convey some of the “topological” ideas that have arisen in the Istanbul Model Theory Seminar after a few sessions. Perhaps I intended to send it out as an email, but it seems I never did. Concerning the Jordan Curve Theorem, I said more in “Knottedness” (September, 2020).

By some popular accounts, topology is “rubber sheet geometry.” If you draw your geometrical figures on a rubber sheet, then the topological properties of the figures are the properties that do not change if you stretch the sheet.

For example, if your figures are block capital letters of the Latin alphabet, the following are topologically the same with one another, because you can write each of them in one motion, without ever returning to the same point:

C G I L M N S V Z

Also E, F, T, and Y are topologically the same with one another, as are D and O. Each of the letters B, P, and Q is topologically unique (among all of the letters). Whether K is topologically the same as H or X depends on how you write it; likewise with A and R.

Is this really mathematics? It is recreational mathematics, anyway, and indeed I probably learned about it in Martin Gardner’s “Mathematical Games” column in Scientific American, to which my godfather gave me a subscription when I was about 12.

Our collection of Martin Gardner books.

The Last Recreations was part of an honorarium from the publisher

for reviewing a submitted manuscript

In his introduction to The Elements of Style, E.B. White says that the chapter that he has added to William Strunk’s original work

is addressed particularly to those who feel that English prose composition is not only a necessary skill but a sensible pursuit as well – a way to spend one’s days.

Apparently Martin Gardner’s column gave the same feeling about mathematics – that it too is a way to spend one’s days – to me and other future mathematicians. He can be praised highly for this. However, since he was not really a mathematician himself, he offered a lopsided view of the subject.

Topology is not just a kind of game or puzzle. Gardner did indeed acknowledge this, saying near the beginning of one column:

People who have a casual interest in mathematics may get the idea that a topologist is a mathematical playboy who spends his time making Moebius bands and other diverting topological models. If they were to open any recent textbook of topology, they would be surprised. They would find page after page of symbols, seldom relieved by a picture or diagram. It is true that topology grew out of the consideration of geometrical puzzles, but today it is a jungle of abstract theory. Topologists are suspicious of theorems that must be visualized in order to be understood.

Gardner’s column appears as Chapter 7, “Curious Topological Models,” of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions (1959; published in Pelican Books, 1965; reprinted, 1971). This book was originally in my spouse’s collection. I found the quote when I went looking through the few Gardner anthologies that we have, seeking in vain the article mentioning the topology of letters.

Gardner continued the quoted column with an investigation of diverting topological models. He was not prepared to present topology as an axiomatic system or as a general framework that makes connections between seemingly disparate areas of mathematics.

But topology is these things. I did not start to understand this until I had a course in topology in graduate school. Then I wrote excitedly about the subject to a correspondent who had been a classmate in college. He had been writing me all kinds of nonsense, so I wrote him back with my own topological nonsense, which however made eminent sense to me. He told me not to write him about such things again. Nonetheless, I shall continue to write here; if you are not interested, you have probably already stopped reading.

What follows then is my attempt at a popular account of topology as it arises in one mathematician’s life – my own. Perhaps it is really addressed to my younger self, as a supplement to (not a replacement of) Martin Gardner’s columns.

The basic notions of topology are simple in themselves; but perhaps making sense of them is the work of years – years of getting used to various levels of abstraction in mathematics. Nonetheless, I shall try to make some sense of topological notions now.

In a precalculus course, one deals with so-called open intervals and closed intervals of the real number line. The numbers that are strictly greater than −1.49 and strictly less than 2.2 (for example) constitute an open interval, denoted by (−1.49, 2.2); if we include also the endpoints −1.49 and 2.2 themselves, then we obtain the closed interval denoted by . The notions of being open and closed are topological notions. They apply to sets. For example, we may say:

-

the open interval (2.7, 3) is the set of numbers that are greater than 2.7 and less than 3;

-

the open interval (2.7, 3) is the set of points on the number line that are to the right of 2.7 and to the left of 3.

Some elementary textbooks describe a set as “any collection of objects,” but this may leave the reader with two questions:

-

Is there a collection of things that are not objects?

-

What is a collection anyway?

I prefer just to say that the word set is simply the most general collective noun that the ordinary mathematician will use. The set theorist has a more general collective noun: class. Actually there can be no most general collective noun; but I propose the word collection itself for the most general collective noun that we shall actually need. Still, in ordinary mathematics, set and collection are synonyms.

A set of points is just a multitude of points – possibly an infinite multitude, or an infinitude –, considered as one thing.

One may move on in one’s studies, to calculus and then to “real analysis,” the theoretical side of calculus. In analysis, one will encounter other kinds of open and closed sets. One will see a definition of them in terms of a notion of distance.

Topology goes further. It manages to keep the notions of open and closed, while throwing away the notion of distance.

Let me try to explain. Say we have three points on a sheet of paper. We label the points as p, q, and r. There is a distance between p and q, say 2 inches. There is a distance between p and r, say 3 inches. Then we know that the distance between q and r is no greater than 5 inches. The technical term is that the sheet of paper is a “metric space” with respect to our usual notion of distance.

A metric space is a kind of topological space. More precisely, a metric on a space determines a topology on the space. But there are topological spaces that are not “metrizable” – whose topologies do not arise from a metric.

Suppose you draw a simple closed curve on the sheet of paper: you start and end at the same point, but otherwise never return to the same point. Your curve might be the letter O or D, or just a weird blob. Then you have divided the sheet into three sets of points:

- the set A of points inside the curve;

- the set B of points on the curve;

- the set C of points outside the curve.

In fact this very claim is supposed to be a deep topological theorem, called the Jordan Curve Theorem; but I was not impressed by it when, as a young person, I read about it in popular accounts (possibly including one of Martin Gardner’s). I am not going to talk further about the theorem (which is still not of great interest to me, at my level of development). I shall just rely on intuition to make the following claim:

Every point p of B is close to the set A in the following sense. For every distance you name, there is a point of A that is closer to p than that distance: every circle you draw around p contains points of A. Here “zero” is not a distance, and there is no circle of radius zero. However, we shall allow that a point of A itself is also close to A.

Similarly, every point of B is close to C.

Suppose now there is a subset D of some set E. This means every point of D lies also in E. Then obviously every point that is close to D is close to E. This observation will be used as a lemma in the proof of the theorem to be announced presently.

A set X of points on our paper will be called closed if every point that is close to X is already in X. Then we have the following four-part theorem. I have tried to arrange the parts from easiest to hardest.

-

The whole sheet of paper, considered as the set of its points, is closed.

Proof. There is really nothing to prove. Every point of the sheet is already on the sheet; in particular, every point of the sheet that is close to the set of points on the sheet is on the sheet. ◻

-

The set of no points – the empty set – is also closed.

Proof. No points are close to the empty set; so, vacuously, every point that is close to the empty set is in the empty set. ◻

-

Suppose we have a collection of closed sets of points. Then we can form the set F of points p such that p belongs to every set of the collection. This set F is closed.

Proof. The set F is a subset of every set in the collection. Therefore, if q is close to F, it is close to every set in the collection, by the lemma mentioned above. But those sets are closed; so q must belong to each of them; therefore it belongs to F. Thus F is closed. ◻

-

Suppose G and H are two closed sets of points. Then we can form the set K of points p such that p lies either in G or in H. This set K is closed.

Proof. Suppose p is close to K. We must show that p is already in K. There are two cases to consider.

-

If p is close to G, then it is in G, since G is closed; therefore it is in K, by definition of K.

-

Suppose p is not close to G. Then there is some distance d such that no points of G are within the distance d of p. But now let e be any distance. Then there is a point of H that is within e of p. Indeed, let f be the lesser of d and e. Since p is close to K, there is a point q of K that is within f of p. In particular, q is within d of p (since f is less than d or equal to d). Therefore q does not lie in G. But q lies in K; so it must lie in H. And q is within e of p. So we have shown that p is close to H. But H is closed; so p must lie in H; therefore it lies in K. ◻

-

The proof of the four-part theorem is now complete. Part 3 can be expressed tersely as:

- The intersection of a collection of closed sets is itself closed.

This collection may be infinite. Part 4 is then:

- The union of a collection of two closed sets is closed.

It follows that the union of a finite collection of closed sets is closed. However, the union of an infinite collection of closed sets need not be closed. For example, on the number line, for each positive number, there is a closed interval consisting of all numbers that are greater than that number or equal to that number. The union of the collection of all such intervals is just the set of positive numbers. This is an open interval, but it is not closed.

For the record, an open set is just the complement of a closed set: it is the set of points that lie outside of a closed set. It is possible for the same set to be both open and closed: for example, the set of all points of a metric space is both open and closed. Moreover, some sets are neither open nor closed.

Apparently this terminology can be frustrating. Somewhere on YouTube, there is a clip of a movie in German about Hitler. In this clip, Hitler must be going crazy about losing the war through the incompetence of his men. I’m not sure, because I do not understand German. Evidently Hitler’s men try to placate him. English subtitles have been added to the clip, to suggest that the men are teaching him, and teaching him …topology. He becomes enraged to be reminded yet again that, if a set is not closed, this does not mean it is open.

The punch line of our present investigations is this. A topological space consists of some things called “points,” together with a notion of “closedness” that satisfies the theorem above:

-

The whole space must be closed.

-

The empty set of points of the space must be closed.

-

The intersection of a collection of closed sets of points of the space must be closed.

-

The union of a collection of two closed sets of points of the space must be closed.

There is no requirement that the notion of closedness be derived from any notion of distance.

The punch line is not really the definition of a topological space, but the fact that the notion of topological space turns out to be useful and ubiquitous in mathematics.

For example, let us return to our sheet of paper; but we consider it now as equipped with a so-called Cartesian coordinate system: every point of the paper corresponds to an ordered pair (a, b) of so-called real numbers a and b. (Probably we are thinking of the paper as having infinite extent now.) A polynomial equation, like x2 + 2xy + 2y2 = 1, has a solution set: in this example, it is the set of those points (corresponding to) pairs (a, b) such that a2 + 2ab + 2b2 = 1. We may consider the set of solutions of more than one equation at a time: perhaps the equation above, along with x + y = 0. In this case the solution set has just two points: (1, −1) and (−1, 1).

In honor of a mathematician whom I know almost nothing about, we refer to the solution set of some polynomial equations as being Zariski closed. It is an easy theorem that the Zariski closed sets do indeed constitute the closed sets of a topology on our sheet of paper. The key point is that, if A is the solution set of the equation f(x, y) = 0, and B is the solution set of g(x, y) = 0, then the union of A and B is the solution set of f(x, y) ⋅ g(x, y) = 0.

The topology in which the closed sets are the Zariski closed sets is unsurprisingly called the Zariski topology. It is quite a bit different from the “usual” topology that we derived earlier by considering distances. Zariski closed sets are closed in the “usual” sense; but most sets that are closed in the usual sense are not Zariski closed. For example, the “closed disk” comprising the points having distance 1 or less from (0, 0) is indeed closed in the “usual” sense; but it is not Zariski closed.

Nonetheless, the Zariski topology is quite useful in the field called algebraic geometry. That name was puzzling for me, yet romantic, when I encountered it on entering graduate school. To me, geometry was what Euclid did, and algebra was symbol manipulation. How would they be combined in a meaningful way? I was excited to think I was going to find out.

A more abstract version of the Zariski topology is useful in logic too. Here the “points” are “complete theories”; and the “polynomial equations” are just “sentences” that are true or false in a given theory. A particular theory “solves” the sentence if the sentence is true in the theory.

Now I can say something more about what we are doing in the Istanbul Model Theory Seminar; but I shall not attempt to explain all technical terms. We are studying free groups. Groups are a notion from algebra. But we are interested in the theories of the various free groups, and in particular in the theorem that all free groups in fact have the same theory. This is a theorem of logic, or more precisely model theory.

For any positive integer n, there is a free group Fn on n generators. All groups with n generators can be considered as “quotients” of Fn. The set of these quotients can be called 𝒢(n). It turns out that this set can be given a metric, the “Gromov–Hausdorff metric.” Here we enter “geometric group theory.” The paper that we are reading makes use of the Gromov–Hausdorff metric.

But the set 𝒢(n) can also be considered as a space of theories with the generalized Zariski topology mentioned above. This topology is the same as the topology that arises from the Gromov–Hausdorff metric.

As far as I can tell so far, we never actually need the metric, but only the topology. To me, using the metric makes some arguments seem more complicated than need be.

Now, if we fix a “large” free group F, then all groups of interest to us can be considered as being “quotients” of F. The set of all of these quotients can be considered …