In high school, if not sooner, one learns theorems established more than two millenia ago by Euclid and Archimedes. I am thinking of the theorems expressed today by the equations

𝐶 = 2π𝑟,

𝐴 = π𝑟²

for the circumference and area of a circle whose radius is 𝑟, and

𝐴 = 4π𝑟²,

𝑉 = (4/3)π𝑟³

for the surface area and volume of a sphere whose radius is 𝑟. One may also learn about the curves that Apollonius called parabola, ellipse, and hyperbola and that are given today by instances of the general quadratic equation

𝐴𝑥² + 𝐵𝑥𝑦 + 𝐶𝑦² + 𝐷𝑥 + 𝐸𝑦 + 𝐹 = 0.

Such notation as this was introduced in the seventeenth century by Descartes, who apparently used it also to understand the curve given by the cubic equation

(𝑦² − 𝑎²)(𝑦 − 𝑏) = 𝑎𝑥𝑦.

Decartes showed that the curve in question could be generated as in the animation below, where a parabola slides along its axis, and a straight line has one point fixed and one point moving with the parabola, and the points of intersection of this straight line with the parabola give us the desired curve.

It may indeed be true that no ancient mathematicians managed to understand the curve. Nonetheless, I think they could have, even without Cartesian algebraic notation. This is what I want to look at.

That we still learn ancient mathematics is not as well recognized as it should be. Thus in January, 2023, a book review began,

No one today would dream of practising the physics, medicine or biology of the ancient Greeks. But their thoughts on how to live remain perennially inspiring.

We still practice the mathematics of the Greeks, and some of us take inspiration from it.

The review was of a book about Epicurus called Living for Pleasure, by Emily A. Austin. The reviewer was Julian Baggini, whose own philosophical work I have referred to a few times on this blog, most recently in “Dicaeology,” on the first part of Book V of the Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle.

Baggini could also have mentioned Greek poetry, such as the Iliad. C.S. Lewis did that, in the 1939 sermon called “Learning in War-Time”:

Before I went to the last war I certainly expected that my life in the trenches would, in some mysterious sense, be all war. In fact, I found that the nearer you got to the front line the less everyone spoke and thought of the allied cause and the progress of the campaign; and I am pleased to find that Tolstoi, in the greatest war book ever written, records the same thing – and so, in its own way, does the Iliad.

I recently turned that sermon into a page of this blog, because the result of the recent US Presidential election had been compared to war.

Before the winner of that election was elected the first time, I wrote a post called “Life in Wartime,” concerning a terror bombing here in Turkey.

Life went on, as I noted in my next blog post, “War Continues,” written after the coup attempt of July, 2016. As I noted, many people on social media turned out to be experts on Turkish politics, at least in their own minds. Now they turn out to be experts at winning a US Presidential election, even though, for some reason, they have not put their expertise to use.

In “War Continues,” I wrote also about having engaged in international cooperation for the sake of proving theorems.

As my wife pointed out to me, another mathematician wrote about such cooperation, when he blogged in response to the recent US election:

But there is one precious thing mathematics has, that almost no other field currently enjoys: a consensus on what the ground truth is, and how to reach it. Because of this, even the strongest differences of opinion in mathematics can eventually be resolved, and mistakes realized and corrected. This consensus is so strong, we simply take it for granted: a solution is correct or incorrect, a theorem is proved or not proved, and when a problem is solved, we simply move on to the next one. This is, sadly, not a state of affairs elsewhere. But if my students can learn from this and carry these skills – such as distinguishing an overly simple but mathematically flawed “solution” from a more complex, but accurate actual solution – to other spheres that have more contact with the real world, then my math lectures have consequence. Even – or perhaps, especially – in times like these.

Thus wrote Terence Tao, of the University of California, Los Angeles, who was born in 1975 in Adelaide, Australia, to immigrants from Hong Kong. Ayşe and I once heard him deliver a talk in Paris. That’s how international mathematics is, “in times like these,” when an advisor of a US Presidential candidate can say at a rally, “America is for Americans and Americans only,” and that candidate can win.

Where Tao refers to “contact with the real world,” I would refer instead to the political world, or something like that. The theorems that I mentioned in the beginning are some of the realest things we know, precisely because we continue to learn them, even after two thousand years, and they are true.

As I said, the symbolism that we use to express the theorems came later.

- In 1557, Robert Recorde gave us the equals sign.

- In 1637, René Descartes gave us polynomial equations as we know them today, albeit without using Recorde’s equals sign.

I talk a lot about the symbolism in “On Commensurability and Symmetry” (Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, July 2017). The Greeks did not use any of it. For Euclid, in Proposition 2 of Book XII of the Elements,

Οἱ κύκλοι πρὸς ἀλλήλους εἰσὶν | Circles are to one another ὡς τὰ ἀπὸ τῶν διαμέτρων τετράγωνα. | as the squares on the diameters.

This is among the most difficult theorems in all thirteen books of the Elements – most difficult to prove, since one needs what will later be called infinitesimal calculus. We sweep all of that under the rug when we write the theorem as

𝐴 = π𝑟².

This may be why some people are afraid of equations, as I suggested in “Thales of Miletus” (December, 2016).

Words corresponding to

𝐶 = 2π𝑟

could be,

Circumferences of circles are to one another as the diameters.

Strictly, this gives us only that the ratio of the circumference to the radius of a circle is always the same. Such a theorem cannot be established in the Elements. There, the ratio in question in undefined, because there is no way to compare straight lines with curved lines. Archimedes comes up with a way, and so he can give us, as the first proposition of Measurement of a Circle,

Πᾶς κύκλος ἴσος ἐστὶ | Every circle is equal τριγώνῳ ὀρθογωνίῳ, | to a right triangle, οὗ | where ἡ μὲν ἐκ τοῦ κέντρου | the radius ἴση | is equal μιᾷ τῶν περὶ τὴν ὀρθήν, | to one of the legs, ἡ δὲ περίμετρος | and the circumference τῇ βάσει. | to the base.

Thus, if the ratio of the circumference to the radius of a circle be denoted by 2π, then the area of the circle of radius 𝑟 must be π𝑟².

The remaining two equations, for the sphere,

𝐴 = 4π𝑟²,

𝑉 = (4/3)π𝑟³,

are pretty much Propositions 33 and 34 of the work of Archimedes On the Sphere and the Cylinder I:

Πάσης σφαίρας ἡ ἐπιφάνεια | The surface of every sphere τετραπλασία ἐστὶ | is the quadruple τοῦ μεγίστου κύκλου | of the greatest circle τῶν ἐν αὐτῇ. | of those in it.

and

Πᾶςα σφαῖρα | Every sphere τετραπλασία ἐστὶ | is the quadruple κώνου | of the cone τοῦ βάσιν μὲν ἔχοντος | having base ἴσην τῷ μεγίστῳ κύκλῳ | equal to the greatest circle τῶν ἐν τῇ σφαίρᾳ, | of those in the sphere, ὕψος δὲ | and height τὴν ἐκ τοῦ κέντρου τῆς σφαίρας | the radius of the sphere.

One does need to incorporate Proposition 10 of Book XII of Euclid’s Elements:

Πᾶς κῶνος | Every cone κυλίνδρου τρίτον μέρος ἐστὶ | is the third part of the cylinder τοῦ τὴν αὐτὴν βάσιν ἔχοντος αὐτῷ | having the same base as it καὶ ὕψος ἴσον. | and equal height.

In the letter addressed to Eudemus at the head of the Conics, Apollonius writes,

The third book contains many incredible theorems of use for the construction of solid loci and for limits of possibility of which the greatest part and the most beautiful are new. And when we had grasped these, we knew that the three-line and four-line locus had not been constructed by Euclid, but only a chance part of it and that not very happily. For it was not possible for this construction to be completed without the additional things found by us.

The translation is by R. Catesby Taliaferro (revised edition, Santa Fe, New Mexico: Green Lion Press, 2000), who spells out some of the meaning, in Apollonian terms, in an appendix.

Given a triangle ABC, we may ask for the locus of points, the product of whose distances from AB and BC bears to the square of the distance from AC a given ratio δ. In Cartesian terms, if the distances from AB and AC are x and y respectively, then the distance from BC is an affine combination αx + βy + c, and thus our locus is given by

αx2 + βxy + cx = δy2.

Without writing this out, perhaps one can still understand that the locus is a conic section tangent to AB and BC at A and C respectively.

Given now a quadrilateral ABCD, we may ask for the locus of points, the product of whose distances from AB and CD bears to the product of the distances from BC and DA a given ratio. The locus is a conic section passing through the vertices of the quadrilateral.

Suppose now we are given

- a straight line;

- parallel to it, two more straight lines, on either side, at a distance a (or a and −a, respectively);

- a fourth straight line, parallel to the first at a distance b from it;

- a fifth straight line, at right angles to the other four.

Decartes asks for the locus of points, the product of whose distances from the second, third, and fourth lines is equal to the product of a and the product of the distances from the fifth and first lines. Strictly, for Descartes, b = 2a, but it doesn’t matter. If the distances from the fifth and first lines are x and y respectively, then the locus is given by

(y + a)(y − a)(y − b) = axy,

or alternatively,

(y2 − a2)/ay = x/(y − b).

If we define z by

az = y2,

then our equation reduces to

(z − a)/y = x/(y − b).

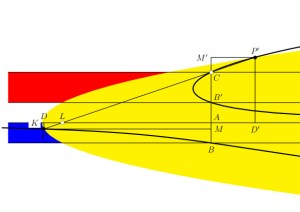

This needs some interpretation. Suppose then our fifth line crosses the first four at A, B, B′, and C respectively, as in the diagram below.

Let a point of our locus be P, and let the foot of its perpendicular to the fifth line be M. Let CP intersect the first line at L, and let the parallel to the fifth line through P meet the first line at D. Then we have similar triangles LDP and PMC. This gives us the last equation, provided z − a is the distance of L from D. We allow this distance to be counted as negative. Let K be at the distance z from D. Then the next-to-last equation defines a parabola with vertex K and axis the first line, and P is where the parabola meets CL.

It is not clear to me that Cartesian notation has really helped.

2 Trackbacks

[…] recognize one another across space; mathematicians, time as well, as I observed in “A Five Line Locus”: we still learn the rules discovered by Archimedes about the surface area and volume of a […]

[…] Archimedes needs two mean proportionals between two lengths, in order to construct a sphere equal to a given cylinder. He has already shown that the cylinder circumscribing a sphere is half again as large as the sphere; this is because, as I quoted him in “A Five Line Locus,” […]