I alluded to this post in my last one, “Perception Deception.” There I questioned the gnomic assertion of its title.

The questioning then consisted of little more than quoting De Anima, where Aristotle points out that a sense cannot be deceived by its proper object. In particular, sight detects color infallibly.

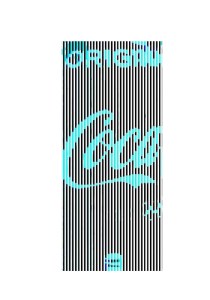

I do not recall the source of this particular image, which I saved on March 29, 2024. The concept, at least, is apparently due to Akiyoshi Kitaoka.

If you see red in the image above, you are not mistaken, even if none of the pixels is of a kind called red.

You are not mistaken, whatever you see. You may be wrong in what you infer from your perception. Aristotle points this out too.

As far as I can tell, you are wrong if you infer that the image is composed with red pixels. When enlarged, the image seems to rely only on the color cyan for the appearance of red. Nonetheless, I have not been able to reproduce the red color very well in images like the one below, whose composition calls explicitly only on cyan.

I created the image above using LaTeX with the pstricks package. I used gimp to convert the resulting ps file to a jpg file. The latter does not have quite the same appearance as the former.

As for the first image, I don’t think you are wrong if you see there a can of Coke, even though René Magritte might well say, Ceci n’est pas une canette de Coca-Cola.

Yes, it’s not a cannette, but an image of one. In that case though, if you do hold an actual can in front of your eyes, what you “really” see is light impinging on your retinas, not the “can itself.”

If you really push such a theory, I think you end up with absurd conclusions, such as that Homer wrong to think dawn was rosy-fingered (ῥοδοδάκτυλος), or the sea was wine-colored (οἶνοψ).

People cannot always be wrong in how they use their own words.

Concerning the original image, apparently you are wrong if you think it is sending light to your eye in the range of frequencies called red. Myself, if I cut away the “background,” as above, then I still see the can as red, but less so.

If I cut away the lettering on the can, leaving the parts that “should” be pure red, as below, then they no longer are red. Those parts are still red in the context of the original picture. Indeed, if they aren’t, then what makes us curious about the image in the first place?

One might say the original can looks red, but isn’t. In that case, the can really does look red. As Descartes points out in the Meditations, (the First and the Second, respectively),

At length I am forced to admit that there is nothing, among the things I once believed to be true, which it is not permissible to doubt.

Thus it must be granted that, after weighing everything carefully and sufficiently, one must come to the considered judgment that the statement “I am, I exist” is necessarily true every time it is uttered by me or conceived in my mind.

Like Aristotle, I am being stricter than Descartes. You are not permitted to doubt that you see red in the first image, if indeed you do see it.

I alluded to this post in the previous post, when I got to the question of whether the difficulty of De Anima was itself an imitation of the difficulty of its subject.

Aristotle describes some arts as imitations in the Poetics. At the end of this post are chapters I–V of the Greek text (with some line breaks, bullets, and comments inserted by me). Before that comes a summary (more detailed for chapters I–III than for the others).

Thus this post is like the ones that I made for the Nicomachean Ethics. Later posts on the Poetics may take up respectively

- chapters VI–XII,

- chapters XIII–XVIII,

- chapters XIX–XXVI.

However, I may not decide to devote the time to making those posts.

Yes, I am in a Catherine Project group reading the Poetics in four weeks (Thursdays, 12:00–13:00 ET; eight or seven hours later here in Istanbul, depending on daylight savings time).

Our group discussed De Anima in fourteen sessions; before that, selections from the Physics in four sessions.

Unless “Perception Deception” be counted, I did not make blog posts for the De Anima readings, in part to save time. I am not sure now that I shall be able to continue posting on the Poetics; still, I have missed such posting.

Aristotle uses also another word for imitation – or at least for those who engage in it: ἀπεικάζοντες (§ I.4), meaning those who make a copy from (ἀπό) an image or “icon” (εἰκών).

In this reading, the word τέχνη “art” comes up only in chapter I, in §§ 4 and 10. I suppose ποιήσις is just one of the arts that can be called mimêsis. Perhaps poiêsis comprises several of those arts. It is not then clear to me what distinguishes poetry from certain other arts, such as shoemaking, or shipbuilding, or doctoring (that is, healing). All of these arts would seem to aim at copying, at least: copying shoes, or ships, or healthy bodies.

I find a clue in how Aristotle says in § I.2, “most of fluting and harping” (τῆς αὐλητικῆς ἡ πλείστη καὶ κιθαριστικῆς) is imitative. I propose that playing is not imitative, precisely when it aims only to copy something external, such as a bird or cicada, or wind in the trees. Otherwise the player is copying his or her own feelings, and this is true imitation.

Contents and Summary

- Introduction (chapter I, §§ 1–3)

- § 1. Topics will include the mythoi of a good poetic work.

- § 2. The following performing arts are all instances of mimêsis:

- Epopee (epic poetry).

- Tragedy.

- Comedy.

- Dithyramb.

- Fluting.

- Harping.

- § 3. The first three chapters will take up

- Medium (that in which,οἷς).

- Object (what [or whom], ἅ).

- Manner (how, ὥς).

- Medium (chapter I, §§ 4–10)

- § 4. Works of poetry may be performed in

- rhythm,

- speech,

- tune (harmonia).

The first and last are used for playing e.g.

- flute,

- harp,

- pipe.

- § 5. Rhythm in dance imitates

- character (ἦθος),

- experience (πάθος),

- action (πρᾶξις).

- §§ 6–9. Metered speech alone has no name.

- § 10. All of the media are in use by some arts:

- dithyramb,

- nome,

- tragedy,

- comedy.

- § 4. Works of poetry may be performed in

- Object (chapter II).

- Who is portrayed may be

- good (σπουδαῖος),

- bad (φαῦλος).

They may be

- better (βελτίων) than we, as in tragedy;

- worse (χείρων) than we, as in comedy;

- such (τοιοῦτος) as we.

- Who is portrayed may be

- Means (chapter III). The means can be

- narration,

- acting,

- both.

- Origin (chapter IV).

- Poetry has two natural causes (§ 1), which are instinctive (σύμφυτος):

- History (§§ 7–15).

- Treated by the more

- serious is the beautiful;

- trivial is the mean (§ 7).

- We know no satire before Homer, e.g. Margites (§ 8).

- Margites : Comedy :: {Iliad, Odyssey} : Tragedy (§ 9).

- Tragedy and comedy started as improvisation (αὐτοσχεδιαστικός.

- Treated by the more

- Comedy (chapter V).

Text

Project Perseus cites the Greek text below as

Aristotle. ed. R. Kassel, Aristotleʼs Ars Poetica. Oxford, Clarendon Press. 1966.

[1447a]

I

§ I.1

[8]

- περὶ

- ποιητικῆς αὐτῆς τε καὶ

- τῶν εἰδῶν αὐτῆς,

ἥν τινα δύναμιν ἕκαστον ἔχει, καὶ

- πῶς δεῖ συνίστασθαι τοὺς μύθους [10]

εἰ μέλλει καλῶς ἕξειν ἡ ποίησις, ἔτι δὲ - ἐκ

- πόσων καὶ

- ποίων ἐστὶ μορίων, ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ

- περὶ τῶν ἄλλων

ὅσα τῆς αὐτῆς ἐστι μεθόδου,

λέγωμεν

ἀρξάμενοι κατὰ φύσιν πρῶτον ἀπὸ τῶν πρώτων.

Aristotle seems to be laying out four topics:

- The species of poetry.

- How a “poem” or work of art is to be well constructed.

- The parts of a poem.

- Anything else relevant.

One might come up with a different enumeration.

A key point is that a poem may indeed be successful (καλῶς ἕξειν) or not.

Perhaps the parts of a poem, or work of art, are rather parts of poetry, that is, the process of making works of art. Perhaps we shall see.

§ I.2

- ἐποποιία δὴ καὶ

- ἡ τῆς τραγῳδίας ποίησις ἔτι δὲ

- κωμῳδία καὶ

- ἡ διθυραμβοποιητικὴ καὶ

- τῆς [15] αὐλητικῆς ἡ πλείστη καὶ

- κιθαριστικῆς

πᾶσαι τυγχάνουσιν οὖσαι μιμήσεις τὸ σύνολον·

We are talking about six performing arts:

- Epopee (epic poetry).

- Tragedy.

- Comedy.

- Dithyramb.

- Fluting.

- Harping.

We may distinguish these from visual arts, which however will come up later in this reading:

- For an analogy in § 4, τινες ἀπεικάζοντες “some imitators”;

- Painters in § II.1.

Here is the key term, mimêsis. I do not recall ever having a sense that I understood it. It seemed to mean that a work of art always looked like something else; however, this made little sense to me if the work of art was produced with flute or harp.

Now I suggest that, as an artist, one is imitating or reproducing oneself, or being oneself consciously. One is expressing something, but this involves looking at something and trying to get it right.

§ I.3

διαφέρουσι δὲ ἀλλήλων τρισίν,

- ἢ γὰρ τῷ ἐν ἑτέροις μιμεῖσθαι

- ἢ τῷ ἕτερα

- ἢ τῷ ἑτέρως καὶ μὴ τὸν αὐτὸν τρόπον.

This is a plan for the first three chapters, where are taken up respectively:

- That in which (“medium”: rhythm, speech, tune).

- What (“object”: people better or worse than, or such as, we are).

- How (“manner” – or voice I would say: one’s own or somebody else’s).

§ I.4

ὥσπερ γὰρ

- καὶ

- χρώμασι καὶ

- σχήμασι

πολλὰ μιμοῦνταί τινες ἀπεικάζοντες

- (οἱ μὲν [20] διὰ τέχνης

- οἱ δὲ διὰ συνηθείας),

- ἕτεροι δὲ διὰ τῆς φωνῆς,

οὕτω κἀν ταῖς εἰρημέναις τέχναις ἅπασαι μὲν ποιοῦνται τὴν μίμησιν ἐν

- ῥυθμῷ καὶ

- λόγῳ καὶ

- ἁρμονίᾳ,

τούτοις δ᾽

- ἢ χωρὶς

- ἢ μεμιγμένοις·

The main distinction is not quite between visual and performing arts, but perhaps “objective” and performing:

- The former may even be

- not art (ἡ τέχνη), but only

- experience (acquaintance, habit; ἡ συνηθεία).

They use

- color,

- shape, and

- sound

to produce an object of contemplation.

- The latter, which are arts, use

- rhythm,

- speech (in § 6, this can be λόγος ψιλός “bare speech” or τὸ μέτρον “meter”; in § 10, only the latter is named),

- “harmony” or tune (also in § 10, τὸ μέλος is used in place of ἡ ἁρμονία)

to make the artist himself into that which – or rather him who – is to be attended to. (I don’t know whether Aristotle will contemplate female artists.)

Art as such (τέχνη) is mentioned again (in this reading) only in the final section (§ 10) of this Chapter I.

If poetry is imitative art, what are the other arts – don’t they imitate some plan, as described by Socrates in the Republic?

In the rest of this chapter are distinguished where the media are used:

- Rhythm and tune: “music” in the modern sense (this section).

- Rhythm alone: dance (§ 5).

- Speech alone: no name (§§ 6–9).

- All (§ 10):

- dithyrambic and nomic poetry (all at once);

- tragedy and comedy (separately).

οἷον

- ἁρμονίᾳ μὲν καὶ

- ῥυθμῷ

χρώμεναι μόνον

- ἥ τε αὐλητικὴ καὶ

- ἡ κιθαριστικὴ κἂν

- εἴ τινες [25] ἕτεραι τυγχάνωσιν οὖσαι τοιαῦται τὴν δύναμιν,

οἷον ἡ τῶν συρίγγων,

§ I.5

αὐτῷ δὲ τῷ ῥυθμῷ [μιμοῦνται] χωρὶς ἁρμονίας ἡ τῶν ὀρχηστῶν (καὶ γὰρ οὗτοι διὰ τῶν σχηματιζομένων ῥυθμῶν μιμοῦνται καὶ

- ἤθη καὶ

- πάθη καὶ

- πράξεις)·

§ I.6

- ἡ δὲ [ἐποποιία] μόνον τοῖς λόγοις ψιλοῖς

- ἡ τοῖς [1447b] μέτροις καὶ τούτοις

- εἴτε μιγνῦσα μετ᾽ ἀλλήλων

- εἴθ᾽ ἑνί τινι γένει χρωμένη τῶν μέτρων

ἀνώνυμοι τυγχάνουσι μέχρι τοῦ νῦν·

§ I.7

οὐδὲν γὰρ ἂν [10] ἔχοιμεν ὀνομάσαι κοινὸν

- τοὺς

- Σώφρονος καὶ

- Ξενάρχου

μίμους καὶ

- τοὺς Σωκρατικοὺς λόγους

οὐδὲ εἴ τις διὰ

- τριμέτρων ἢ

- ἐλεγείων ἢ

- τῶν ἄλλων τινῶν τῶν τοιούτων

ποιοῖτο τὴν μίμησιν.

πλὴν οἱ ἄνθρωποί γε συνάπτοντες τῷ μέτρῳ

- τὸ ποιεῖν ἐλεγειοποιοὺς

- τοὺς δὲ ἐποποιοὺς

ὀνομάζουσιν,

- οὐχ ὡς [15] κατὰ τὴν μίμησιν ποιητὰς

- ἀλλὰ κοινῇ κατὰ τὸ μέτρον προσαγορεύοντες·

If it seems silly to go into the distinctions here, suggests Aristotle, look at how people recognize poetry for its meter rather than its mimêsis.

§ I.8

καὶ γὰρ ἂν

- ἰατρικὸν ἢ

- φυσικόν τι

διὰ τῶν μέτρων ἐκφέρωσιν,

οὕτω καλεῖν εἰώθασιν·

οὐδὲν δὲ κοινόν ἐστιν

- Ὁμήρῳ καὶ

- Ἐμπεδοκλεῖ

πλὴν τὸ μέτρον, διὸ

- τὸν μὲν ποιητὴν δίκαιον καλεῖν,

- τὸν δὲ φυσιολόγον μᾶλλον ἢ [20] ποιητήν·

Aristotle does not approve of calling everybody a poet.

§ I.9

ὁμοίως δὲ κἂν εἴ τις ἅπαντα τὰ μέτρα μιγνύων ποιοῖτο τὴν μίμησιν

καθάπερ Χαιρήμων ἐποίησε Κένταυρον μικτὴν ῥαψῳδίαν ἐξ ἁπάντων τῶν μέτρων,

καὶ ποιητὴν προσαγορευτέον.

περὶ μὲν οὖν τούτων διωρίσθω τοῦτον τὸν τρόπον.

§ I.10

εἰσὶ δέ τινες αἳ πᾶσι χρῶνται τοῖς [25] εἰρημένοις,

λέγω δὲ οἷον

- ῥυθμῷ καὶ

- μέλει καὶ

- μέτρῳ,

ὥσπερ

- ἥ τε τῶν διθυραμβικῶν ποίησις καὶ

- ἡ τῶν νόμων καὶ

- ἥ τε τραγῳδία καὶ

- ἡ κωμῳδία·

διαφέρουσι δὲ ὅτι

- αἱ μὲν ἅμα πᾶσιν

- αἱ δὲ κατὰ μέρος.

ταύτας μὲν οὖν λέγω τὰς διαφορὰς τῶν τεχνῶν ἐν οἷς ποιοῦνται τὴν μίμησιν. [1448a]

II

§ II.1

ἐπεὶ δὲ μιμοῦνται οἱ μιμούμενοι πράττοντας,

ἀνάγκη δὲ τούτους

- ἢ σπουδαίους

- ἢ φαύλους

εἶναι

(τὰ γὰρ ἤθη σχεδὸν ἀεὶ τούτοις ἀκολουθεῖ μόνοις,

- κακίᾳ γὰρ καὶ

- ἀρετῇ

τὰ ἤθη διαφέρουσι πάντες),

- ἤτοι βελτίονας ἢ καθ᾽ ἡμᾶς

- ἢ χείρονας [5]

- ἢ καὶ τοιούτους,

ὥσπερ οἱ γραφεῖς·

- Πολύγνωτος μὲν γὰρ κρείττους,

- Παύσων δὲ χείρους,

- Διονύσιος δὲ ὁμοίους εἴκαζεν.

Concerning people, the only distinction worth making is whether they are such as we, or better or worse than we.

§ II.2

δῆλον δὲ ὅτι

- καὶ τῶν λεχθεισῶν ἑκάστη μιμήσεων ἕξει ταύτας τὰς διαφορὰς

- καὶ ἔσται ἑτέρα τῷ ἕτερα μιμεῖσθαι τοῦτον τὸν τρόπον.

§ II.3

- καὶ γὰρ ἐν

- ὀρχήσει καὶ

- αὐλήσει καὶ [10]

- κιθαρίσει

ἔστι γενέσθαι ταύτας τὰς ἀνομοιότητας,

- καὶ [τὸ] περὶ

- τοὺς λόγους δὲ καὶ

- τὴν ψιλομετρίαν,

οἷον

- Ὅμηρος μὲν βελτίους,

- Κλεοφῶν δὲ ὁμοίους,

- Ἡγήμων δὲ ὁ Θάσιος τὰς παρῳδίας ποιήσας πρῶτος καὶ

Νικοχάρης ὁ τὴν Δειλιάδα χείρους·

§ II.4

ὁμοίως δὲ

- καὶ περὶ τοὺς διθυράμβους

- καὶ περὶ τοὺς [15] νόμους,

ὥσπερ †γᾶς† Κύκλωπας Τιμόθεος καὶ Φιλόξενος μιμήσαιτο ἄν τις.

ἐν αὐτῇ δὲ τῇ διαφορᾷ καὶ ἡ τραγῳδία πρὸς τὴν κωμῳδίαν διέστηκεν·

- ἡ μὲν γὰρ χείρους

- ἡ δὲ βελτίους μιμεῖσθαι βούλεται τῶν νῦν.

III

§ III.1

ἔτι δὲ τούτων τρίτη διαφορὰ τὸ ὡς ἕκαστα τούτων [20] μιμήσαιτο ἄν τις. καὶ γὰρ ἐν

- τοῖς αὐτοῖς καὶ

- τὰ αὐτὰ

μιμεῖσθαι ἔστιν ὁτὲ μὲν ἀπαγγέλλοντα,

- ἢ ἕτερόν τι γιγνόμενον ὥσπερ Ὅμηρος ποιεῖ

- ἢ ὡς τὸν αὐτὸν καὶ μὴ μεταβάλλοντα,

- ἢ πάντας ὡς πράττοντας καὶ ἐνεργοῦντας †τοὺς μιμουμένους†.

§ III.2

ἐν τρισὶ δὴ ταύταις διαφοραῖς ἡ μίμησίς ἐστιν, [25] ὡς εἴπομεν κατ᾽ ἀρχάς,

ἐν

- οἷς τε <καὶ

- ἃ> καὶ

- ὥς.

ὥστε

- τῇ μὲν ὁ αὐτὸς ἂν εἴη μιμητὴς Ὁμήρῳ Σοφοκλῆς,

μιμοῦνται γὰρ ἄμφω σπουδαίους, - τῇ δὲ Ἀριστοφάνει,

πράττοντας γὰρ μιμοῦνται καὶ δρῶντας ἄμφω.

§ III.3

ὅθεν καὶ δράματα καλεῖσθαί τινες αὐτά φασιν,

ὅτι μιμοῦνται δρῶντας.

διὸ καὶ [30] ἀντιποιοῦνται

- τῆς τε τραγῳδίας καὶ

- τῆς κωμῳδίας

οἱ Δωριεῖς

(τῆς μὲν γὰρ κωμῳδίας

- οἱ Μεγαρεῖς οἵ τε ἐνταῦθα

ὡς ἐπὶ τῆς παρ᾽ αὐτοῖς δημοκρατίας γενομένης καὶ - οἱ ἐκ Σικελίας,

ἐκεῖθεν γὰρ ἦν Ἐπίχαρμος ὁ ποιητὴς πολλῷ πρότερος ὢν - Χιωνίδου καὶ

- Μάγνητος·

καὶ τῆς τραγῳδίας ἔνιοι [35] τῶν ἐν Πελοποννήσῳ)

ποιούμενοι τὰ ὀνόματα σημεῖον·

- αὐτοὶ μὲν γὰρ κώμας τὰς περιοικίδας καλεῖν φασιν,

- Ἀθηναίους δὲ δήμους,

ὡς κωμῳδοὺς

- οὐκ ἀπὸ τοῦ κωμάζειν λεχθέντας

- ἀλλὰ τῇ κατὰ κώμας πλάνῃ ἀτιμαζομένους ἐκ τοῦ ἄστεως· [1448b]

καὶ τὸ ποιεῖν αὐτοὶ μὲν δρᾶν,

Ἀθηναίους δὲ πράττειν προσαγορεύειν.

§ III.4

περὶ μὲν οὖν τῶν διαφορῶν

- καὶ πόσαι

- καὶ τίνες

τῆς μιμήσεως εἰρήσθω ταῦτα.

IV

§ IV.1

ἐοίκασι δὲ γεννῆσαι μὲν ὅλως τὴν ποιητικὴν

αἰτίαι [5] δύο τινὲς καὶ αὗται φυσικαί.

§ IV.2

- τό τε γὰρ μιμεῖσθαι

σύμφυτον τοῖς ἀνθρώποις ἐκ παίδων ἐστὶ καὶ - τούτῳ διαφέρουσι τῶν ἄλλων ζῴων ὅτι

- μιμητικώτατόν ἐστι καὶ

- τὰς μαθήσεις ποιεῖται διὰ μιμήσεως τὰς πρώτας, καὶ

- τὸ χαίρειν τοῖς μιμήμασι πάντας.

§ IV.3

σημεῖον δὲ τούτου τὸ συμβαῖνον [10] ἐπὶ τῶν ἔργων·

ἃ γὰρ αὐτὰ λυπηρῶς ὁρῶμεν,

τούτων τὰς εἰκόνας τὰς μάλιστα ἠκριβωμένας χαίρομεν θεωροῦντες,

οἷον

- θηρίων τε μορφὰς τῶν ἀτιμοτάτων καὶ

- νεκρῶν.

§ IV.4

αἴτιον δὲ καὶ τούτου,

ὅτι μανθάνειν

- οὐ μόνον τοῖς φιλοσόφοις ἥδιστον

- ἀλλὰ καὶ τοῖς ἄλλοις ὁμοίως,

ἀλλ᾽ ἐπὶ βραχὺ [15] κοινωνοῦσιν αὐτοῦ.

§ IV.5

διὰ γὰρ τοῦτο χαίρουσι τὰς εἰκόνας ὁρῶντες,

ὅτι συμβαίνει θεωροῦντας

- μανθάνειν καὶ

- συλλογίζεσθαι τί ἕκαστον,

οἷον ὅτι οὗτος ἐκεῖνος·

ἐπεὶ ἐὰν μὴ τύχῃ προεωρακώς,

- οὐχ ᾗ μίμημα ποιήσει τὴν ἡδονὴν

- ἀλλὰ διὰ τὴν ἀπεργασίαν

- ἢ τὴν χροιὰν

- ἢ διὰ τοιαύτην τινὰ ἄλλην αἰτίαν. [20]

Does it matter that we can recognize things in a portrait or landscape whose specific subject is unknown?

§ IV.6

κατὰ φύσιν δὲ ὄντος ἡμῖν

- τοῦ μιμεῖσθαι καὶ

- τῆς ἁρμονίας καὶ

- τοῦ ῥυθμοῦ

(τὰ γὰρ μέτρα

ὅτι μόρια τῶν ῥυθμῶν

ἐστι φανερὸν)

ἐξ ἀρχῆς οἱ πεφυκότες πρὸς αὐτὰ μάλιστα κατὰ μικρὸν προάγοντες

ἐγέννησαν τὴν ποίησιν

ἐκ τῶν αὐτοσχεδιασμάτων.

§ IV.7

διεσπάσθη δὲ κατὰ τὰ οἰκεῖα ἤθη

ἡ ποίησις· [25]

- οἱ μὲν γὰρ σεμνότεροι

- τὰς καλὰς ἐμιμοῦντο πράξεις καὶ

- τὰς τῶν τοιούτων,

- οἱ δὲ εὐτελέστεροι τὰς τῶν φαύλων,

πρῶτον ψόγους ποιοῦντες,

ὥσπερ ἕτεροι- ὕμνους καὶ

- ἐγκώμια.

§ IV.8

τῶν μὲν οὖν πρὸ Ὁμήρου οὐδενὸς ἔχομεν εἰπεῖν τοιοῦτον ποίημα,

εἰκὸς δὲ εἶναι πολλούς,

ἀπὸ δὲ Ὁμήρου ἀρξαμένοις [30] ἔστιν,

οἷον ἐκείνου ὁ Μαργίτης καὶ τὰ τοιαῦτα.

ἐν οἷς κατὰ τὸ ἁρμόττον καὶ τὸ ἰαμβεῖον ἦλθε μέτρον, διὸ καὶ ἰαμβεῖον καλεῖται νῦν,

ὅτι ἐν τῷ μέτρῳ τούτῳ ἰάμβιζον ἀλλήλους.

§ IV.9

καὶ ἐγένοντο τῶν παλαιῶν

- οἱ μὲν ἡρωικῶν

- οἱ δὲ ἰάμβων ποιηταί.

ὥσπερ δὲ καὶ τὰ σπουδαῖα μάλιστα ποιητὴς Ὅμηρος [35] ἦν (μόνος γὰρ οὐχ ὅτι εὖ ἀλλὰ καὶ μιμήσεις δραματικὰς ἐποίησεν),

οὕτως καὶ τὸ τῆς κωμῳδίας σχῆμα πρῶτος ὑπέδειξεν,

οὐ ψόγον ἀλλὰ τὸ γελοῖον δραματοποιήσας·

ὁ γὰρ Μαργίτης ἀνάλογον ἔχει,

ὥσπερ

- Ἰλιὰς καὶ ἡ

- Ὀδύσσεια

πρὸς τὰς τραγῳδίας, [1449a]

οὕτω καὶ οὗτος πρὸς τὰς κωμῳδίας.

§ IV.10

παραφανείσης δὲ τῆς

- τραγῳδίας καὶ

- κωμῳδίας

οἱ ἐφ᾽ ἑκατέραν τὴν ποίησιν ὁρμῶντες κατὰ τὴν οἰκείαν φύσιν

- οἱ μὲν ἀντὶ τῶν ἰάμβων κωμῳδοποιοὶ [5] ἐγένοντο,

- οἱ δὲ ἀντὶ τῶν ἐπῶν τραγῳδοδιδάσκαλοι,

διὰ τὸ

- μείζω καὶ

- ἐντιμότερα

τὰ σχήματα εἶναι ταῦτα ἐκείνων.

§ IV.11

τὸ μὲν οὖν ἐπισκοπεῖν εἰ ἄρα ἔχει ἤδη ἡ τραγῳδία τοῖς εἴδεσιν ἱκανῶς ἢ οὔ,

αὐτό τε καθ᾽ αὑτὸ κρῖναι καὶ πρὸς τὰ θέατρα,

ἄλλος λόγος.

§ IV.12

γενομένη δ᾽ οὖν ἀπ᾽ ἀρχῆς [10] αὐτοσχεδιαστικῆς –

- καὶ αὐτὴ

- καὶ ἡ κωμῳδία,

καὶ

- ἡ μὲν ἀπὸ τῶν ἐξαρχόντων τὸν διθύραμβον,

- ἡ δὲ ἀπὸ τῶν τὰ φαλλικὰ

ἃ ἔτι καὶ νῦν ἐν πολλαῖς τῶν πόλεων διαμένει νομιζόμενα –

κατὰ μικρὸν ηὐξήθη προαγόντων ὅσον ἐγίγνετο φανερὸν αὐτῆς·

καὶ πολλὰς μεταβολὰς μεταβαλοῦσα ἡ [15] τραγῳδία ἐπαύσατο,

ἐπεὶ ἔσχε τὴν αὑτῆς φύσιν.

§ IV.13

καὶ τό τε τῶν ὑποκριτῶν πλῆθος ἐξ ἑνὸς εἰς δύο πρῶτος Αἰσχύλος ἤγαγε καὶ τὰ τοῦ χοροῦ ἠλάττωσε καὶ τὸν λόγον πρωταγωνιστεῖν παρεσκεύασεν·

- τρεῖς δὲ καὶ

- σκηνογραφίαν

Σοφοκλῆς.

§ IV.14

ἔτι δὲ τὸ μέγεθος·

- ἐκ μικρῶν μύθων καὶ [20]

- λέξεως γελοίας

διὰ τὸ ἐκ σατυρικοῦ μεταβαλεῖν ὀψὲ ἀπεσεμνύνθη,

τό τε μέτρον ἐκ τετραμέτρου ἰαμβεῖον ἐγένετο.

- τὸ μὲν γὰρ πρῶτον τετραμέτρῳ ἐχρῶντο διὰ τὸ σατυρικὴν καὶ ὀρχηστικωτέραν εἶναι τὴν ποίησιν,

- λέξεως δὲ γενομένης αὐτὴ ἡ φύσις τὸ οἰκεῖον μέτρον εὗρε·

μάλιστα γὰρ [25] λεκτικὸν τῶν μέτρων τὸ ἰαμβεῖόν ἐστιν·

σημεῖον δὲ τούτου,

πλεῖστα γὰρ ἰαμβεῖα λέγομεν ἐν τῇ διαλέκτῳ τῇ πρὸς ἀλλήλους,

ἑξάμετρα δὲ ὀλιγάκις καὶ ἐκβαίνοντες τῆς λεκτικῆς ἁρμονίας.

§ IV.15

ἔτι δὲ ἐπεισοδίων πλήθη.

καὶ τὰ ἄλλ᾽ ὡς [30] ἕκαστα κοσμηθῆναι λέγεται ἔστω ἡμῖν εἰρημένα·

πολὺ γὰρ ἂν ἴσως ἔργον εἴη διεξιέναι καθ᾽ ἕκαστον.

V

§ V.1

ἡ δὲ κωμῳδία ἐστὶν ὥσπερ εἴπομεν μίμησις φαυλοτέρων μέν,

οὐ μέντοι κατὰ πᾶσαν κακίαν,

ἀλλὰ τοῦ αἰσχροῦ ἐστι τὸ γελοῖον μόριον.

τὸ γὰρ γελοῖόν ἐστιν [35] ἁμάρτημά τι καὶ αἶσχος ἀνώδυνον καὶ οὐ φθαρτικόν,

οἷον εὐθὺς τὸ γελοῖον πρόσωπον

- αἰσχρόν τι καὶ

- διεστραμμένον

ἄνευ ὀδύνης.

§ V.2

- αἱ μὲν οὖν τῆς τραγῳδίας μεταβάσεις καὶ δι᾽ ὧν ἐγένοντο οὐ λελήθασιν,

- ἡ δὲ κωμῳδία διὰ τὸ μὴ σπουδάζεσθαι ἐξ ἀρχῆς ἔλαθεν· [1449b]

καὶ γὰρ χορὸν κωμῳδῶν ὀψέ ποτε ὁ ἄρχων ἔδωκεν,

ἀλλ᾽ ἐθελονταὶ ἦσαν.

ἤδη δὲ σχήματά τινα αὐτῆς ἐχούσης οἱ λεγόμενοι αὐτῆς ποιηταὶ μνημονεύονται.

§ V.3

τίς δὲ

- πρόσωπα ἀπέδωκεν ἢ

- προλόγους ἢ [5]

- πλήθη ὑποκριτῶν καὶ

- ὅσα τοιαῦτα,

ἠγνόηται.

τὸ δὲ μύθους ποιεῖν

- [Ἐπίχαρμος καὶ

- Φόρμις]

τὸ μὲν ἐξ ἀρχῆς ἐκ Σικελίας ἦλθε,

τῶν δὲ Ἀθήνησιν Κράτης πρῶτος ἦρξεν ἀφέμενος τῆς ἰαμβικῆς ἰδέας καθόλου ποιεῖν

- λόγους καὶ

- μύθους.

§ V.4

- ἡ μὲν οὖν ἐποποιία τῇ τραγῳδίᾳ μέχρι μὲν τοῦ [10] μετὰ μέτρου λόγῳ μίμησις εἶναι σπουδαίων ἠκολούθησεν·

- τῷ δὲ τὸ μέτρον ἁπλοῦν ἔχειν καὶ ἀπαγγελίαν εἶναι,

ταύτῃ διαφέρουσιν·

ἔτι δὲ τῷ μήκει·

- ἡ μὲν ὅτι μάλιστα πειρᾶται ὑπὸ μίαν περίοδον ἡλίου εἶναι ἢ μικρὸν ἐξαλλάττειν,

- ἡ δὲ ἐποποιία ἀόριστος τῷ χρόνῳ καὶ τούτῳ διαφέρει,

καίτοι [15] τὸ πρῶτον ὁμοίως ἐν ταῖς τραγῳδίαις τοῦτο ἐποίουν καὶ ἐν τοῖς ἔπεσιν.

§ V.5

μέρη δ᾽ ἐστὶ

- τὰ μὲν ταὐτά,

- τὰ δὲ ἴδια τῆς τραγῳδίας·

διόπερ

- ὅστις περὶ τραγῳδίας οἶδε

- σπουδαίας καὶ

- φαύλης,

- οἶδε καὶ περὶ ἐπῶν·

- ἃ μὲν γὰρ ἐποποιία ἔχει,

ὑπάρχει τῇ τραγῳδίᾳ, - ἃ δὲ αὐτῇ,

οὐ πάντα ἐν τῇ [20] ἐποποιίᾳ.

Edited April 18, 2025. Among other things, I had to correct the sentence, “I suppose ποιήσις is just one of the arts, or several of the arts, but not all, that can be called poiêsis.” That last transliterated Greek word should have been mimêsis.

2 Trackbacks

[…] « Imitation Limitation […]

[…] “Imitation Limitation” […]