Aristotle was the subject of the last three posts on this blog:

- “Perception Deception”

- The Philosopher asserts in De Anima that the eyes cannot be in error about color; Josef Albers contradicts this.

- “Imitation Limitation”

- In the Poetics, Aristotle seems to use mimêsis as a differentia of poiêsis among the technai. Arts not poetry are nonetheless imitative, but perhaps artists are to be distinguished for imitating themselves.

- “Purity Obscurity”

- Does catharsis clean the emotions, or wash them away?

Two more posts might have taken up the latter half of the Poetics, but they never materialized.

I turn now to the work held under the arm of Aristotle’s teacher, at the center of Raphael’s School of Athens.

Altınova, Balıkesir, Monday, June 16, 2025

I was able to start reading Plato’s Timaeus at the beach during the Feast of the Sacrifice. In the dialogue, Critias describes Timaeus as being “our best astronomer” (ὄντα ἀστρονομικώτατον ἡμῶν, 27a).

At the beach, I also happened to read (or read from) Wendell Berry, Essays 1993–2017, and Immanuel Kant, Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals. I shall be looking at those works too here, and others

The same person who led the Aristotle group for the Catherine Project is now leading a Timaeus group. She has also been leading a guerrilla group on Euclid since not long after its proposal by me in the winter of 2023. In that group, five of us are now in Elements Book X, reputedly “La croix des mathématiciens,” although (or because) it develops results on incommensurability that may have been of interest to Plato.

Plato may not distinguish between mathematics and what we today call physics. Alternatively, he may find the latter only a crude version of the former.

Though a theorem be graven in stone, or set on a stone in relief with bronze letters, or for that matter scrawled on a wall with magic marker, the truth is not a physical property of the letters. I argued for such a thing in “Anthropology of Mathematics.”

I took these photographs in 2011: in

- Paris, Saturday, June 4, and

- Istanbul (Süleymaniye district, Fatih borough), Sunday, October 30.

Somebody, perhaps young, had got excited about

- Euler’s Identity, eiπ + 1 = 0, relating five special constants, 0, 1, e, π and i, by applying, once each, the operations of addition, multiplication, and exponentiation; and

- Descartes’s discovery that a geometric figure such as a circle can be defined by an algebraic equation such as x² + y² = 1.

When young, I thought Euler’s Identity was somehow cheating for involving imaginary numbers. How could it be saying anything about the ratio, which Archimedes had approximated, of the circumference of a circle to the diameter? Perhaps I am still not sure how to answer that, but ez would seem to be defined “naturally” as

1 + z + z²/2 + z³/2⋅3 + z⁴/2⋅3⋅4 + …

The ear hears the harmony of the musical intervals called diapason, diapente, and diatessaron (octave, fifth, and fourth). These are the audible forms of the ratios of one to two, two to three, and three to four respectively. The first of these ratios is compounded of the latter two. The difference or rather quotient of the latter two ratios is the ratio of eight to nine, whose audible form is the tone. Six instances of this ratio, compounded together, make just a little more than an octave (for, they make the ratio of 262 144 to 531 441, as Euclid points out in the Sectio Canonis, and twice 262 144 is only 524 288).

We still make music as if six tones gave us exactly an octave. Excepting the most exquisitely perceptive among us, we may not hear the anomaly. This would seem to corroborate my point that mathematical truth is not a physical property.

That could be a subtext of Plato as well, but it is not actually my present concern, which is, briefly:

- Plato’s greatest lesson, as Hannah Arendt observes, may be that doing injustice is worse than suffering it.

- Nonetheless, he is interested in “neutral” topics, such as the problem of finding two mean proportionals between two lengths.

- Moreover, he is not interested in practical solutions – at least not by the account of Plutarch.

- Plato may engage in what R. G. Collingwood calls scientific persecution. It is not for the layman to tell the scientist what to do.

- In that case, neither is it for the latter to tell the former. Steven Weinberg does it anyway, as Mary Midgley points out.

- There are responsibilities to being in a community, even at a university, as Wendell Berry points out.

- In distinguishing physics from religion, Weinberg distinguishes it also from mathematics, I would say, because here our concern is not the “outer” world, but an “inner” one, albeit one that is accessible in principle to everybody, ancient as well as modern.

- Weinberg thinks he is a moral person. Immanuel Kant does too. We all do.

- We are not moral, as Berry points out. He does not even have to refer to climate change for this, although perhaps one can so appeal (see for example Jessica Wildfire, “We’re About to Watch Billions Die. Where Does ‘Empathy’ Fit Here?” The Sentinel Intelligence, June 23, 2025.)

Saturday, June 14, 2025. In Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals, Kant seems to say, crudely, “We all legislate the same categorical imperative. Unfortunately most people are too stupid to understand this.” He does say, literally (408) – and correctly, in my view,

one could not do morality a worse service than by trying to derive it from examples. For every purported example of morality would first have to be judged according to principles of morality …

There is more of this below. Kant goes on to allude to the story of the rich young man, told in all three synoptic gospels – for example, in Matthew 19:16–22, the climax being verse 21: “If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come and follow me.” I have not been able to figure out what Kant thinks of this hypothetical imperative.

By the account of Timaeus in the Platonic dialogue named for him, a god constructed the cosmos out of what had already existed (31b–32c). C. F. von Weizsäcker noted this in “Science and the Modern World,” which is Chapter 1 of The Relevance of Science (London, 1964) and was annotated by me in “Religious Science.” To build the universe, the god used

- fire, for visibility;

- earth, for tangibility.

These two constituents had to be held together by something else: a mean, or perhaps more than one. A single mean would have sufficed in a planar world; however, for our solid world, two means were needed. Fortunately they were at hand: air and water.

Plato would seem thus to be fancifully combining two theories:

- the theory of four elements, apparently due to Empedocles;

- the theory of numbers, as would be presented in Books VII–IX of the Elements of Euclid.

The Greek word stoicheion for “element” is the same in either case; however, if I understand correctly, the word will not be used in the Timaeus until 48b–c – here with the 1929 translation of Bury in the Loeb Classical Library:

τὴν δὴ πρὸ τῆς οὐρανοῦ γενέσεως πυρὸς ὕδατός τε καὶ ἀέρος καὶ γῆς φύσιν θεατέον αὐτὴν καὶ τὰ πρὸ τούτου πάθη· νῦν γὰρ οὐδείς πω γένεσιν αὐτῶν μεμήνυκεν, ἀλλ᾽ ὡς εἰδόσιν πῦρ ὅτι ποτέ ἐστιν καὶ ἕκαστον αὐτῶν λέγομεν ἀρχὰς αὐτὰ τιθέμενοι στοιχεῖα τοῦ παντός, προσῆκον αὐτοῖς οὐδ᾽ ἂν ὡς ἐν συλλαβῆς [48ξ] εἴδεσιν μόνον εἰκότως ὑπὸ τοῦ καὶ βραχὺ φρονοῦντος ἀπεικασθῆναι.

We must gain a view of the real nature of fire and water, air and earth, as it was before the birth of Heaven, and the properties they had before that time; for at present no one has as yet declared their generation, but we assume that men know what fire is, and each of these things, and we call them principles and presume that they are elements of the Universe, although in truth they do not so much as deserve to be likened with any likelihood, [48c] by the man who has even a grain of sense, to the class of syllables.

For completeness, here is the passage already mentioned:

σωματοειδὲς δὲ δὴ καὶ ὁρατὸν ἁπτόν τε δεῖ τὸ γενόμενον εἶναι, χωρισθὲν δὲ πυρὸς οὐδὲν ἄν ποτε ὁρατὸν γένοιτο, οὐδὲ ἁπτὸν ἄνευ τινὸς στερεοῦ, στερεὸν δὲ οὐκ ἄνευ γῆς· ὅθεν ἐκ πυρὸς καὶ γῆς τὸ τοῦ παντὸς ἀρχόμενος συνιστάναι σῶμα ὁ θεὸς ἐποίει. δύο δὲ μόνω καλῶς συνίστασθαι τρίτου χωρὶς [31ξ] οὐ δυνατόν· δεσμὸν γὰρ ἐν μέσῳ δεῖ τινα ἀμφοῖν συναγωγὸν γίγνεσθαι. δεσμῶν δὲ κάλλιστος ὃς ἂν αὑτὸν καὶ τὰ συνδούμενα ὅτι μάλιστα ἓν ποιῇ, τοῦτο δὲ πέφυκεν ἀναλογία κάλλιστα ἀποτελεῖν. ὁπόταν γὰρ ἀριθμῶν τριῶν εἴτε ὄγκων [32α] εἴτε δυνάμεων ὡντινωνοῦν ᾖ τὸ μέσον, ὅτιπερ τὸ πρῶτον πρὸς αὐτό, τοῦτο αὐτὸ πρὸς τὸ ἔσχατον, καὶ πάλιν αὖθις, ὅτι τὸ ἔσχατον πρὸς τὸ μέσον, τὸ μέσον πρὸς τὸ πρῶτον, τότε τὸ μέσον μὲν πρῶτον καὶ ἔσχατον γιγνόμενον, τὸ δ᾽ ἔσχατον καὶ τὸ πρῶτον αὖ μέσα ἀμφότερα, πάνθ᾽ οὕτως ἐξ ἀνάγκης τὰ αὐτὰ εἶναι συμβήσεται, τὰ αὐτὰ δὲ γενόμενα ἀλλήλοις ἓν πάντα ἔσται. εἰ μὲν οὖν ἐπίπεδον μέν, βάθος δὲ μηδὲν ἔχον ἔδει γίγνεσθαι τὸ τοῦ παντὸς σῶμα, μία μεσότης ἂν ἐξήρκει [32β] τά τε μεθ᾽ αὑτῆς συνδεῖν καὶ ἑαυτήν, νῦν δὲ στερεοειδῆ γὰρ αὐτὸν προσῆκεν εἶναι, τὰ δὲ στερεὰ μία μὲν οὐδέποτε, δύο δὲ ἀεὶ μεσότητες συναρμόττουσιν· οὕτω δὴ πυρός τε καὶ γῆς ὕδωρ ἀέρα τε ὁ θεὸς ἐν μέσῳ θείς, καὶ πρὸς ἄλληλα καθ᾽ ὅσον ἦν δυνατὸν ἀνὰ τὸν αὐτὸν λόγον ἀπεργασάμενος, ὅτιπερ πῦρ πρὸς ἀέρα, τοῦτο ἀέρα πρὸς ὕδωρ, καὶ ὅτι ἀὴρ πρὸς ὕδωρ, ὕδωρ πρὸς γῆν, συνέδησεν καὶ συνεστήσατο οὐρανὸν ὁρατὸν καὶ ἁπτόν.

According to the bolded passages,

- there had to be a bond joining the two;

- this is most beautifully accomplished proportionally;

- solids never with one, but always with two means do they harmonize; thus,

- in the middle of fire and earth, the god put water and air.

In modern terms, fire, air, water, earth constitute a geometric sequence, at least in the story told by Timaeus.

Numbers can do that, in Book VIII of the Elements. Euclid then calls them ἀριθμοὶ ἑξῆς ἀνάλογον, “numbers in continued proportion.” Proposition 1 is announced as,

Ἐὰν ὦσιν | If be ὁσοιδηποτοῦν ἀριθμοὶ | however many numbers ἑξῆς ἀνάλογον, | continually proportional, οἱ δὲ ἄκροι αὐτῶν | and the extremes of them πρῶτοι πρὸς ἀλλήλους | prime to one another ὦσιν, | be, ἐλάχιστοί εἰσι | least they are τῶν τὸν αὐτὸν λόγον | of those the same ratio ἐχόντων αὐτοῖς. | having with them.

I want to investigate this for a while, before returning to Plato, because we may have forgotten the ancient way of thinking on the mathematics.

Suppose we are given a sequence, such as Α, Β, Γ, Δ, in which consecutive terms all have the same ratio. This means, in particular,

Α : Β :: Β : Γ

– in words,

- Α is to Β as Β is to Γ, or

- Α has to Β the ratio of Β to Γ, or

- Α, Β, Β, Γ are in proportion.

Also,

Β : Γ :: Γ : Δ,

and so on if there are more terms in the sequence. Suppose also that the first and last terms of the sequence, here Α and Δ, are prime to one other. Whenever we have another sequence, of the same length, in which consecutive terms all have the same ratio as before, then the terms of the new sequence are respectively greater than those of the original sequence. This is because, the new sequence being Ε, Ζ, Η, Θ, we have

Α : Δ :: Ε : Θ.

This proportion yields Α < Ε and Δ < Θ, by Book VII, Proposition 21, which is that two numbers prime to one another are (respectively) least of all numbers in their ratio.

Some two numbers are the least in their ratio, and these then measure (today, “divide”) all numbers in that ratio, by Proposition VII.20. Barry Mazur says of this, in “How Did Theaetetus Prove His Theorem?” –

I don’t quite follow Euclid’s proof of this pivotal proposition, and I worry that there may be a tinge of circularity in the brief argument given in his text. It is peculiar, though, that Euclid’s commentarists, very often quite loquacious about other issues, seem to be strangely silent about Proposition 20 and its opaque proof.

I have to agree that Euclid does not spell out all details that a modern reader might want. He is not writing for the modern reader. Book VII starts out sensibly enough, with what we call the Euclidean Algorithm. This algorithm gives us the greatest common measure of any two numbers. I talked about it in 2015, in “The Facebook Algorithm.” Today, we may not see why Euclid should distinguish two propositions:

- If the Euclidean Algorithm, applied to two numbers, results in 1, then those two numbers are prime to one another.

- If two numbers are not prime to one another, then the Algorithm yields their greatest common measure.

The latter proposition is true, even for numbers that are prime to one another, since this just means that their greatest common measure is 1.

Next in Elements VII comes proportion. Briefly, for numbers, the implicit meaning of

Α : Β :: Γ : Δ

is that the Euclidean Algorithm has the same steps, whether applied to Α and Β or to Γ and Δ. This means, assuming Α > Β,

- Β goes into Α as many times as Δ into Γ;

- the remainders go into Β and Δ respectively the same number of times;

- and so forth.

This ensures that the relation of sameness of ratio is transitive, as it ought to be if it is indeed a sameness.

The explicit meaning of the proportion above is that Β is

- the same multiple (double, triple, quadruple …) of Α that Δ is of Γ

- the same part (half, third, fourth …) of Α that Δ is of Γ, or else

- the same parts.

The meaning of being the same parts is shown by the proof of Proposition 4 (which perhaps then in our sense is not really a proof). For Β to be the same parts of Α that Δ is of Γ, it is necessary that the greatest common measure (which could be 1) of Α and Β be the same respective part of them that the greatest common measure of Γ and Δ is of them. The condition is sufficient too, except we may require that Β not be the same multiple or part of Α that Δ is of Γ, since we have already explained what these mean, and it is needed for the definition of being the same parts.

I worked out these things at more length in “The Geometry of Numbers in Euclid,” along with the proof of Proposition 13, that the proportion above entails the alternate form,

Α : Γ :: Β : Δ.

In this case, if neither of Α and Γ measures the other, then the same is true of Β and Δ. By Proposition 13 again, the respective common measures are in the ratio of Α and Β, which are therefore not the least numbers in their ratio. This proves VII.20.

A consequence is what we call Euclid’s Lemma, that a number prime to either of two numbers is prime to their product. For, if Α × Β is not prime to Γ, let Ε be a common measure (other than 1). Then

Α × Β = Ε × Ζ

for some Ζ. By Proposition 19,

Α : Ε :: Ζ : Β.

If Α is prime to Γ, then a fortiori it is prime to Ε. By VII.20 then, Ε must measure Β, which is therefore not prime to Γ.

In Propositions 19, 21, and 27 of Book VIII of the Elements, Euclid establishes that four numbers form a geometric sequence if and only if the first and last numbers are in the ratio of two cube numbers. Evidently Timaeus alludes to this theorem.

Two lengths always have a geometric mean, as Euclid shows in Proposition 13 of Book VI of the Elements. The diagram is as follows.

By similar triangles,

AD : DC :: CD : DB,

but DC is the same as CD, which is therefore the geometric mean of AD and DB.

Given not two lengths, but two similar parallelograms, taking a side of either, we can form a new parallelogram, which is their geometric mean. In the figure below then, let us follow Euclid’s practice of naming parallelograms by two opposite vertices (this is unambiguous in the Greek, since the neuter article is attached, when lines would get the feminine article; see my article “Abscissas and Ordinates”).

We have then

EH : BG :: BG : KF.

We call BG here a “mean proportional” of EH and KF. Back in March of this year (2025), it occurred to me that

- if

- the mean proportional is so called in translation of Euclid’s μέση ἀνάλογον,

- then

- the plural should be “means proportional,” in correspondence with Euclid’s μέσαι ἀνάλογόν.

In the Greek phrases here, ἀνάλογον is grammatically an adverb, originally a prepositional phrase.

As far as I could tell, since the eighteenth century if not earlier, the plural of “mean proportional” has been “mean proportionals.”

We can find two mean proportionals between two similar parallelepipeds, by following the same pattern as for parallelograms.

Ancient geometers worked at finding two mean proportionals between two lengths. Eutocius included their results in his commentary on Archimedes’s two works On the Sphere and the Cylinder. That commentary was included, along with works of Archimedes himself, in a collection made by Isidore of Miletus, an architect of the Hagia Sophia of Constantinople, still standing in the province of Istanbul, where I live. See (Archimedes, p. 14).

Archimedes needs two mean proportionals between two lengths, in order to construct a sphere equal to a given cylinder. He has already shown that the cylinder circumscribing a sphere is half again as large as the sphere; this is because, as I quoted him in “A Five Line Locus,”

Every sphere is the quadruple of the cone having base equal to the greatest circle of those in the sphere, and height the radius of the sphere.

Given now any cylinder, Archimedes can make a new one, half again as tall, on the same base. If he can make a cylinder equal to this one, but with height the same as the diameter of the base, then the inscribed sphere will be equal to the original cylinder.

In modern, Cartesian terms, given a cylinder whose height is h and the diameter of whose base is d, we want a length D so that

d²h = D³

and thus

(d/D)³ = d/h.

There is now a length ℓ such that

d/D = D/ℓ = ℓ/h,

that is, D and ℓ are two mean proportionals of d and h.

If we want two mean proportionals between a and e, this means solving

a/y = y/x = x/e.

We extract two equations:

a/y = y/x, a/y = x/e.

We rewrite these as

ax = y2, ae = xy.

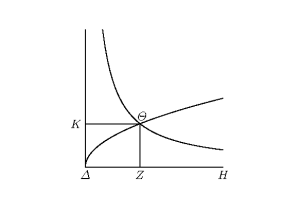

Possibly one recognizes these from high school as equations of the conic sections called parabola and hyperbola respectively. If you graph them, you get such a diagram as the following.

Eutocius attributes the work here to Menaechmus (Archimedes, p. 288). The work includes the diagram, which looks as if comes from an analytic geometry textbook of today. In the diagram, for some lengths A and Ε that determine the parabola through 𝛥 and 𝛩 and the hyperbola through 𝛩 with asymptotes 𝛥H and 𝛥K,

Α : Z𝛩 :: Z𝛩 : 𝛥Z :: 𝛥Z : Ε.

In particular, if Ε is twice Α, then Z𝛩 is the side of a cube whose volume is twice that of the cube whose side is Α.

Thus, it seems, the Delian Problem led Menaechmus to discover the conic sections.

It seems also that Plato did not approve. According to words that Plutarch assigns to one Tyndares in Convivial Questions (Thomas, pp. 388–9, cited by Fowler, p. 293),

Πλάτων αὐτὸς ἐμέμψατο τοὺς περὶ Εὔδοξον καὶ Ἀρχύταν καὶ Μέναιχμον εἰς ὀργανικὰς καὶ μηχανικὰς κατασκευὰς τὸν τοῦ στερεοῦ διπλασιασμὸν ἀπάγειν ἐπιχειροῦντας, ὥσπερ πειρωμένους δι’ ἀλόγου δύο μέσας ἀνάλογον, ᾗ παρείκοι, λαβεῖν· ἀπόλλυσθαι γὰρ οὕτω καὶ διαφθείρεσθαι τὸ γεωμετρίας ἀγαθὸν αὖθις ἐπὶ τὰ αἰσθητὰ παλινδρομούσης τῶν ἀιδίων καὶ ἀσωμάτων εἰκόνων, πρὸς αἷσπερ ὧν ὁ θεὸς ἀεὶ θεός ἐστι.

Plato himself censured Eudoxus and Archytas and Menaechmus for endeavouring to solve the doubling of the cube by instruments and mechanical constructions, thus trying by irrational means to find two mean proportionals, so far as that is allowable: for in this way what is good in geometry would be corrupted and destroyed, falling back again into sensible objects and not rising upward and laying hold of immaterial and eternal images, among which God has his being and remains for ever God.

Plato does have a supreme practical accomplishment: the dissemination of the teaching that his teacher demonstrated with his life. Hannah Arendt takes this up in “Truth and Politics” (1967):

… the Socratic proposition “It is better to suffer wrong than to do wrong” … this sentence has become the beginning of Western ethical thought, and … as far as I know, it has remained the only ethical proposition that can be derived directly from the specifically philosophical experience. (Kant’s categorical imperative, the only competitor in the field, could be stripped of its Judaeo-Christian ingredients, which account for its formulation as an imperative instead of a simple proposition. Its underlying principle is the axiom of non-contradiction – the thief contradicts himself because he wants to keep the stolen goods as his property – and this axiom owes its validity to the conditions of thought that Socrates was the first to discover.)

If the passage from Plutarch is evidence for another teaching disseminated by Plato, it may be scientific persecution, by the account of R. G. Collingwood in The New Leviathan (1942):

1. 5. To think that physics or chemistry ought to be defined in terms of matter or physiology in terms of life is more than an egregious blunder; it is a threat to the existence of science.

1. 51. It implies that people know what matter is without studying physics or chemistry, and what life is without studying physiology.

1. 52. It implies that this non-scientific and pre-scientific knowledge concerning the nature of matter or life is perfect and final, so far as it goes, and can never be corrected by anything science can do.

1. 53. It implies that, if anything scientists imagine themselves to have discovered about matter or life or what not is inconsistent with anything contained or implied in this non-scientific and pre-scientific knowledge, the scientists have made a mistake.

1. 57. At one blow, by enunciating the apparently harmless proposition that physics or chemistry is the science of matter, physiology the science of life, or the like, we have evoked the whole apparatus of scientific persecution; I mean the persecution of scientists for daring to be scientists.

1. 58. In whose interest is such a persecution carried on? Who stands to gain by it? The nominal beneficiary differs from time to time: sometimes it is religion, sometimes statecraft, and so on. None of these has ever in fact gained a ha’porth of advantage. The actual beneficiary has always been obsolete science.

Does anybody benefit then if Plato gets to tell mathematicians what to work on?

What is mathematics anyway? That would seem to be up to the mathematicians to decide.

If laypeople don’t get to tell scientists what to do, perhaps a complementary proposition is also true.

Steven Weinberg apparently thinks highly of his own science, physics, though not much of anything else:

The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless.

But if there is no solace in the fruits of our research, there is at least some consolation in the research itself. Men and women are not content to comfort themselves with tales of gods and giants, or to confine their thoughts to the daily affairs of life; they also build telescopes and satellites and accelerators, and sit at their desks for endless hours working out the meaning of the data they gather. The effort to understand the universe is one of the very few things that lifts [sic] human life a little above the level of farce, and gives [sic] it some of the grace of tragedy.

That passage, from the “excellent and informative little book The First Three Minutes: A Modern View of the Origin of the Universe [1977],” is quoted by Mary Midgley in Evolution as a Religion.

Midgley goes on (pp. 86–7) to say of Weinberg’s work,

Since virtually the whole book has been devoted to expounding astrophysics, not to discussing it as an occupation, and certainly not to discussing other occupations with which it might compete, Weinberg’s readers might find this an unexpected blow. They might feel rather shaken and degraded by the sudden revelation that their lives are probably valueless, and they might also ask the reasonable question: how does Weinberg know?

How indeed does Weinberg know?

The practical autonomy of individual sciences is surely not absolute.

Wendell Berry addresses that autonomy in Life Is a Miracle (2000; pp. 172–3):

If there is an economy of the life of the mind … then that economy, like any other, subsists upon the making of certain choices. You can’t think, read, research, study, learn, or teach everything … We are, moreover, differently talented and are called by different vocations … There can be no objection in principle to organizing a university as a convocation of specialties and specialists; that is what a university is bound to be.

But some serious questions remain … Can this convocation of specialists actually come together? In other words, can the convocation become a conversation? … It would have to understand itself as a part, for better or worse, of the surrounding community … various professional standards would have to submit to the one standard of the community’s health.

This has not happened in our universities … Among the causes, I think, none is more prominent than the by now ubiquitous and nearly exclusive emphasis upon originality and innovation. This emphasis … imposes the choice of work over life …

I have been reading Berry because John Warner wrote in his newsletter,

Wendell Berry’s Life Is a Miracle: An Essay Against Modern Superstition is a great example of a book that’s constructed to argue against the ideas of another, in this case, the concept of “consilience,” Edward O. Wilson’s notion that, essentially, all the questions of life and living could (and should) ultimately yield to understanding through the application of science.

This was on February 5, 2025, when Warner was writing about the work of writers who had “blurbed” his own new book, More Than Words. I could not find Life Is a Miracle in its ultimate form, except as included in a volume of the Library of America. I ordered this, not from Amazon, but from a real bookshop, Pandora Kitabevi. I didn’t get the book till the end of April – in time for the beach. I am sorry now I didn’t order Warner’s book at the same time. Probably I tried, but the book was not in Pandora’s catalogue – it is not there now.

Steven Weinberg accidently shows how mathematics differs from physics, in “Without God” (2008):

… Traditional religions generally rely on authority, whether the authority is an infallible leader, such as a prophet or a pope or an imam, or a body of sacred writings, a Bible or a Koran …

Of course, scientists rely on authorities, but of a very different sort. If I want to understand some fine point about the general theory of relativity, I might look up a recent paper by an expert in the field. But I would know that the expert might be wrong. One thing I probably would not do is to look up the original papers of Einstein, because today any good graduate student understands general relativity better than Einstein did. We progress …

As a mathematician, I look up the work of mathematicians much older than Einstein, not only for the history, but for the mathematics. (I talked about this in “A Five Line Locus.”)

I might even say I am interested more in what is thought than what is sensed, in the terms of Timaeus (27d–8a):

ἔστιν οὖν δὴ κατ᾽ ἐμὴν δόξαν πρῶτον διαιρετέον τάδε· τί τὸ ὂν ἀεί, γένεσιν δὲ οὐκ ἔχον, καὶ τί τὸ γιγνόμενον μὲν ἀεί, ὂν δὲ οὐδέποτε; τὸ μὲν δὴ νοήσει μετὰ λόγου περιληπτόν, ἀεὶ κατὰ ταὐτὰ ὄν, τὸ δ᾽ αὖ δόξῃ μετ᾽ αἰσθήσεως ἀλόγου δοξαστόν, γιγνόμενον καὶ ἀπολλύμενον, ὄντως δὲ οὐδέποτε ὄν.

Now first of all we must, in my judgement, make the following distinction. What is that which is Existent always and has no Becoming? And what is that which is Becoming always and never is Existent? Now the one of these is apprehensible by thought with the aid of reasoning, since it is ever uniformly existent; whereas the other is an object of opinion with the aid of unreasoning sensation, since it becomes and perishes and is never really existent.

The apprehension in either case is still by other human beings, or possibly by other rational beings.

Weinberg’s “Without God” is Berry’s subject in “God, Science, and Imagination” (pp. 538–9):

Perhaps the most interesting thing that Prof. Weinberg says in his essay is this: “There are plenty of people without religious faith who live exemplary moral lives (as for example, me).” This is of course a joke … The large sad fact that gives the joke its magnitude and cutting edge is that there is probably not one person now living in the United States who, by a strict accounting, could be said to be living an exemplary moral life.

I think Berry here is supported by Kant (§2, 408), who (as mentioned earlier) alludes to the story told in the synoptic gospels of the rich young man:

one could not do morality a worse service than by trying to derive it from examples. For every purported example of morality would first have to be judged according to principles of morality, to see whether it is actually worthy to serve as a foundation, i.e. as a model – examples can in no way supply us with the concept of morality in the first place. Even the Holy One of the Gospel must first be compared with our ideal of moral perfection before he is recognized as such. He even says of himself: ‘Why do you call me (whom you see) good? No one is good (the archetype of the good), but God alone (whom you do not see)’.

For Berry (pp. 539),

We are still somewhere in the course of one of the most destructive centuries of human history. And, though I believe I know some pretty good people whom I love and admire, I don’t know one who is not implicated, by direct participation and by proxies given to suppliers, in an economy, recently national and now global, that is the most destructive, predatory, and wasteful the world has ever seen. Our own country in only a few hundred years has suffered the loss of maybe half its arable topsoil …

Monday, June 16, 2025: the author, who, when he moved into a dormitory as a freshman at St John’s College in Annapolis in 1983, posted the following on the door of his (shared) room:

The heaven of modern humanity is indeed shattered in the Cyclopean struggle for wealth and power. The world is groping in the shadow of egotism and vulgarity. Knowledge is bought through a bad conscience, benevolence practiced for the sake of utility. The East and the West, like two dragons tossed in a sea of ferment, in vain strive to regain the jewel of life. We need a Niuka again to repair the grand devastation; we await the great Avatar. Meanwhile, let us have a sip of tea. The afternoon glow is brightening the bamboos, the fountains are bubbling with delight, the soughing of the pines is heard in our kettle. Let us dream of evanescence, and linger in the beautiful foolishness of things.

Thus Okakura Kakuzo in The Book of Tea, first published more than a century ago. In “Early Tulips,” I couldn’t tell how Okakura’s east-west analysis applied to Istanbul. Now I cannot link to more information about Niuka than Okakura tells us in his previous paragraph:

The Taoists relate that at the great beginning of the No-Beginning, Spirit and Matter met in mortal combat. At last the Yellow Emperor, the Sun of Heaven, triumphed over Shuhyung, the demon of darkness and earth. The Titan, in his death agony, struck his head against the solar vault and shivered the blue dome of jade into fragments. The stars lost their nests, the moon wandered aimlessly among the wild chasms of the night. In despair the Yellow Emperor sought far and wide for the repairer of the Heavens. He had not to search in vain. Out of the Eastern sea rose a queen, the divine Niuka, horn-crowned and dragon-tailed, resplendent in her armor of fire. She welded the five-coloured rainbow in her magic cauldron and rebuilt the Chinese sky. But it is told that Niuka forgot to fill two tiny crevices in the blue firmament. Thus began the dualism of love – two souls rolling through space and never at rest until they join together to complete the universe. Everyone has to build anew his sky of hope and peace.

Bibliography

Archimedes. The Two Books On the Sphere and the Cylinder, volume I of The Works of Archimedes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004. Translated into English, together with Eutocius’ commentaries, with commentary, and critical edition of the diagrams, by Reviel Netz.

Hannah Arendt. Truth and politics. The New Yorker, pages 49–88, 25 February 1967.

Wendell Berry. God, science, and imagination. In Essays 1993–2017, pages 532–41. Library of America, 2019. First published 2010.

Wendell Berry. Life is a miracle. In Essays 1993–2017, pages 127–236. Library of America, 2019. First published 2000.

R. G. Collingwood. The New Leviathan, or Man, Society, Civilization, and Barbarism. Clarendon Press, revised edition, 2000. With an Introduction and additional material edited by David Boucher. First edition 1942.

David Fowler. The Mathematics of Plato’s Academy: A new reconstruction. Clarendon Press, Oxford, second edition, 1999.

Immanuel Kant. Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford, 2019. Translated with an Introduction and Notes by Christopher Bennett, Joe Saunders, and Robert Stern.

Mary Midgley. Evolution as a Religion. Routledge, London and New York, revised edition, 2002. With a new introduction by the author. First published 1985.

Okakura Kakuzo. The Book of Tea. Dover, New York, 1964. First published 1906. New Introduction and Afterword by Everett F. Bleiler.

David Pierce. Model-theory of vector-spaces over unspecified fields. Archive for Mathematical Logic, 48(5):421–436, 2009.

David Pierce. Abscissas and ordinates. Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, 5(1):223–264, 2015, 10.5642/jhummath.201501.14.

David Pierce. Thales and the nine-point conic. The De Morgan Gazette, 8(4):27–78, 2016.

David Pierce. On commensurability and symmetry. Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, 7(2):90–148, 2017, 10.5642/jhummath.201702.06.

David Pierce. Conics in place. Annales Universitatis Paedagogicae Cracoviensis | Studia ad Didacticam Mathematicae Pertinentia, May 2022.

Plato. Plato IX. Timaeus, Critias, Cleitophon, Menexenus, Epistles. Number 234 in the Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press and William Heinemann, Cambridge MA and London, 1929. With an English Translation by R. G. Bury.

Ivor Thomas, editor. Selections Illustrating the History of Greek Mathematics. Vol. I. From Thales to Euclid. Number 335 in Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1951. With an English translation by the editor. Supplemented reprint 1980.

Steven Weinberg. Without God. New York Review of Books, 55(14), September 25 2008 (uutampa.org/october-9-2013-without-god-rerun-from-dec-2009/, accessed June 13, 2025).

Edited July 3, 2025, with corrections, more on Archimedes, and references to “A Five Line Locus”

3 Trackbacks

[…] « Astronomy Anomaly […]

[…] last paragraph also, perhaps obscurely, when writing “On Kant’s Groundwork.” I wrote in “Astronomy Anomaly” on being led to Berry’s book by John […]

[…] statement about life is echoed by Steven Weinberg’s, looked at by me in “Astronomy Anomaly” and then “Ethics of […]