Below is my essay on courage, first drafted in April of last year (2024). A reason to think of it now is a recent pair of essays, coming from the United States:

- Holly MathNerd, “The Fist Went Up: a reflection on courage” (July 30, 2025);

- Jessica Wildfire, “Something Stronger Than Hope” (August 4, 2025).

The latter takes up all of the virtues that Socrates does.

Plato didn’t get everything right, but he remains one of the most widely studied philosophers in western history for a reason. In Book IV of The Republic, he discusses the four cardinal virtues. Hope didn’t make the list.

Here they are:

- Wisdom (or prudence)

- Self-control (or temperance)

- Fairness (or justice)

- Fortitude (or courage)

These four virtues feed a healthy society. We’re supposed to teach them to our young and practice them every day. Hope stems from an insufficient knowledge about the world, but fortitude grows out of wisdom.

We’re long on hope, but short on fortitude.

It would be good if we had more fortitude. As Wildfire writes more recently, in “Fighting Fascism at The End of The World: What nobody wants to say” (August 20, 2025),

It’s gotten popular to tell people to physically throw themselves in front of ICE agents to stop arrests. Allow me to pose a rude question: If someone won’t even wear a piece of cloth on their face for a few hours a day, are they going to get thrown in jail to protect someone they don’t even know?

For Aristotle at least, there is a distinction between the two qualities that could be meant by fortitude and courage respectively. The distinction is a theme of my own essay below.

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

Tuesday, July 11, 2023

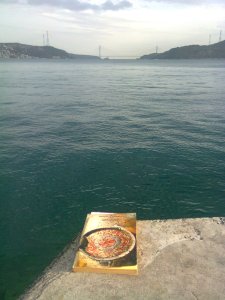

I usually read Rackham’s translation in the Loeb edition

sometimes along the Bosphorus, as here

As for MathNerd, reading her can take fortitude. She is often highly sensible – and then comes a shock:

[A]lmost never do I say everything I want to say.

It’s easy to excuse. I’m a deaf girl who lives alone. I’ve had stalkers. I’ve had messages – detailed, chilling – from men who developed parasocial attachments and decided that an enjoyable comment thread meant destiny.

Cowardice is awfully easy to rationalize … but it’s still cowardice.

I’ve criticized Donald Trump … none of that matters when it comes to respecting the depths of his astonishing courage.

Because when it mattered most – when the stage became a kill zone, when blood streaked his face and the Secret Service swarmed in a blur of guns and shouted commands – he didn’t duck. He didn’t flee.

He didn’t collapse into the armored SUV and vanish into a night of press releases and spin.

He rose.

He raised his fist … It was about instinct. Identity. Will.

And beneath all of that – what makes that kind of reflex even possible – is love.

Love of country. Love of the people he’s standing for.

That kind of courage doesn’t come from ego. It comes from devotion.

I can only wonder whether MathNerd knows the same things about the man in question that I believe I do. What does she make, or would she make, of such stories as Ryan Pickrell, “‘I don’t get it’: Trump said to have questioned why retired Gen. John Kelly’s son fought in Afghanistan — during a Memorial Day visit to his grave” (Business Insider, September 4, 2020). The linked source is Jeffrey Goldberg, “Trump: Americans Who Died in War Are ‘Losers’ and ‘Suckers’” (The Atlantic, September 3, 2020):

On Memorial Day 2017, Trump visited Arlington National Cemetery … He was accompanied on this visit by John Kelly, who was then the secretary of homeland security … The two men were set to visit Section 60, the 14-acre area of the cemetery that is the burial ground for those killed in America’s most recent wars. Kelly’s son Robert is buried in Section 60 … Trump was meant … to join John Kelly in paying respects at his son’s grave, and to comfort the families of other fallen service members. But according to sources with knowledge of this visit, Trump, while standing by Robert Kelly’s grave, turned directly to his father and said, “I don’t get it. What was in it for them?” Kelly (who declined to comment for this story) initially believed, people close to him said, that Trump was making a ham-handed reference to the selflessness of America’s all-volunteer force. But later he came to realize that Trump simply does not understand non-transactional life choices.

“He can’t fathom the idea of doing something for someone other than himself,” one of Kelly’s friends, a retired four-star general, told me. “He just thinks that anyone who does anything when there’s no direct personal gain to be had is a sucker. There’s no money in serving the nation.” Kelly’s friend went on to say, “Trump can’t imagine anyone else’s pain. That’s why he would say this to the father of a fallen marine on Memorial Day in the cemetery where he’s buried.”

By standing up after being shot at, did the presidential candidate exhibit what he could not comprehend in others? Maybe he did, but the case has to be made, and MathNerd doesn’t do it.

Bicycling through Washington DC on a fine spring day in 1997, on my way to explain my dissertation to a member of my committee, I was pushed by somebody in a car. My front wheel hit the curb, the tire burst, and I hit the ground. My saddle broke off, and my elbow was bloodied. I stood up. I walked over to car whose passenger had pushed me; the car was stopped at a red light.

“If you wanted to hurt me, I guess you succeeded.”

“All right,” was the grinning response, and then the light turned green.

Somebody in another car offered me his mobile.

When I told the story later, I may have been annoyed by one or two responses about what I should have done. It is hard to understand what people do on the spur of the moment, when that spur is particularly sharp.

Almost twenty years earlier, when somebody came running at me, yelling and wielding a sword, I wet my pants. (Examples of such incontinence in film come up in “Homer for the Civilian.”)

As for my own essay on courage below, I have tried to improve the style, particularly for the transition from the first to the second paragraph. Still, the essay is substantially as it was when I submitted it to a particular publication. The editors rejected it with a form letter. They mentioned “difficult decisions about which of the many excellent submissions to include.” They supplied some general recommendations, which I summarize thus:

- Stay focused (without too many points).

- Talk about a text (and not just yourself).

- Be accessible (explain technical references).

Did I violate these?

- In my view, everything I wrote was focussed on how war has meaning, even to the civilian; but then I gave many examples.

- I wrote not about a text, but about three: the Iliad, the Nicomachean Ethics, and Beowulf. I used also

- Steven Runciman, The Fall of Constantinople 1453,

- Daniel Callcut, “Toleration is an impressive virtue that’s worth reviving.”

- I quoted from an Iliad translation that used such expressions as “all this hast thou spoken.” Also, I called the essay itself by the old-fashioned word “Valor,” as I had the blog post on the relevant part of the Ethics.

Here is what I have now (after the photo; the essay was not intended to be illustrated).

I’m pretty sure the Loeb volume on the bench

is the first of the two comprising the Iliad

Friday, January 27, 2023

Aristotle does not seem to find true courage on display in the Trojan War. Nonetheless, on the other side of both Europe and the span of a thousand years, Beowulf may exhibit the virtue. We ought to summon our own courage, even when reading and talking about such books as the Iliad, the Nicomachean Ethics, and Beowulf.

Even with books of mathematics, my courage was once tested. The books were mine, in my office, but had been boxed up by somebody who did not know what it meant to treasure them. Our department was being renovated, we had not been warned, and I was on holiday. I felt as disrespected as Comrade Achilles, when Briseis, whom he treasured, was confiscated by General Agamemnon, in Book I of the Iliad.

Well, I couldn’t really feel like Achilles, because I was not a combat veteran. This I was told, by a veteran. The civilian cannot know what it means, he said, to have one’s life always on the line, as Achilles does.

The veteran and I went on to have a good conversation, I think. This was fifteen years ago. (My side of it became “Homer for the Civilian.”)

Fifteen years before that conversation, I was ridiculed by a pilot for being nervous in his small propeller-plane. According to him, I was not putting my life on the line – not as I had just spent eleven days doing, bicycling from Maryland to Michigan, via Ontario, next to cars on highways.

Though I did see plenty of roadkill on that trip, I did not feel threatened by the drivers whizzing past. Perhaps Achilles does not feel threatened on the battlefield. We do differ in our training and experience in killing. I have none.

Must Homer have such training and experience, to be able to tell us of the anatomy of death?

Athena guided the spear upon his nose beside the eye, and it pierced through his white teeth. So, the stubborn bronze shore off his tongue at its root, and the spear-point came out by the base of the chin.

That’s Iliad Book V, lines 290–3, in the old prose translation of Murray in the Loeb Classical Library (1924). The nose belonged to Pandarus; the spear, to Diomedes.

Must Homer have been a gardener, to be able to make the simile in Book VIII, lines 306–8?

And he bowed his head to one side like a poppy that in a garden is laden with its fruit and the rains of spring; so bowed he to one side his head, laden with his helmet.

The soldier is Gorgythion, smitten in the breast with the arrow of Teucer, who was aiming for his victim’s half-brother, Hector.

Homer encourages comparisons of civilian life with military. If we have weighed out the product of our own hands, under the eye of a stingy customer; or if we have been that customer, tired of dealing with crooked tradespeople; then we know what is happening at the Achaean encampment, in Iliad Book XII, lines 430–5:

Yea, everywhere the walls and battlements were spattered with blood of men from both sides, from Trojans and Achaeans alike. Howbeit even so they could not put the Achaeans to rout, but they held their ground, as a careful woman that laboureth with her hands at spinning, holdeth the balance and raiseth the weight and the wool in either scale, making them equal, that she may win a meagre wage for her children.

While the spinning woman and her unmentioned customer may disagree on the value of a mina of wool, they agree on what it means to weigh that much. They have a common measure.

The two sides fighting the Trojan War: have they got a common measure? They haven’t got courage, at least not in a way that Aristotle wants to point out. In Nicomachean Ethics Book III, chapter viii, the Philosopher draws several examples from the Iliad, but only in order to show what courage is not.

Thus Diomedes is not courageous when he tells Nestor, who has urged flight,

Yea, verily, old sir, all this hast thou spoken according to right. But herein dread grief cometh upon my heart and soul, for Hector will some day say, as he speaketh in the gathering of the Trojans: “Tydeus’ son, driven in flight before me, betook him to the ships.” So shall he some day boast – on that day let the wide earth gape for me.

That’s Iliad Book VIII, lines 146–50. Diomedes cares too much for the opinion of others to show proper courage, even if he does stay on the battlefield.

Earlier, he is a threat to Hector’s cousin, until Ares intervenes, in human guise. Speaking as Acamas, leader of the Thracians, the war-god says to the Trojans (V.467–9),

Low lieth a man whom we honoured even as goodly Hector, Aeneas, son of great-hearted Anchises. Nay, come, let us save from out the din of conflict our noble comrade (ἐσθλὸν ἑταῖρον).

As Homer then explains in his own voice,

So saying he aroused the strength and spirit of every man.

If you can use it, the Greek verse is,

Ὥς εἰπὼν ὄτρυνε μένος καὶ θυμὸν ἑκάστου.

The key word has given us the name of a gland in our chest: the thymus. Thumos is translated as spirit, spiritedness, or anger, but this alone is not what courage is. As Aristotle explains,

Thus the real motive of courageous men is the nobility of courage, although spirit operates in them as well.

That’s the translation by Rackham (Loeb Classical Library, 1926, revised 1934); here’s the original (1116b30–1), with the word thumos:

οἱ μὲν οὖν ἀνδρεῖοι διὰ τὸ καλὸν πράττουσιν, ὁ δὲ θυμὸς συνεργεῖ αὐτοῖς·

This is rendered by Sachs (2002),

So while courageous people act on account of the beautiful, spiritedness works along with it in them.

For an example of a noble, beautiful, courageous act, I propose to turn to an epic from the north: Beowulf. Getting ready to face the “ill-starred man” (won-sæli wer, line 105), who has been coming in the night to gobble up Danish warriors, the Geatish hero declines to use manmade implements (lines 677–87):

I do not account myself less liberal of the fruits of war in martial deeds than Grendel does himself; therefore I will not put him to rest with a sword, deprive him of life, though I am fully capable. He does not know the advantages such that he could strike against me, cleave a shield, no matter how skilled he is at violent acts; but in the night we two shall forgo swords if he dares to look for combat without weapons, and afterward let God in his wisdom, the holy Lord assign glory on whichever hand he sees fit.

The translation is by Fulk (The Beowulf Manuscript, Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library, 2010). From his fight with the monster, Beowulf expects no glory, unless he evens the odds, because then he can show true courage.

Fifty years after pulling Grendel’s arm off, Beowulf faces a new foe, a fire-breathing dragon. Now the hero will use artifice (lines 2518–27):

I would not bear a sword, a weapon against the reptile, if I knew how I could otherwise honorably grapple with the troublemaker, as I once did with Grendel; but I expect hot war-flame there, exhalations and poison; therefore I have on me shield and mail-shirt. I do not intend to flee a foot’s pace from the guardian of the barrow, but it will turn out for us in a fight by the wall as the ruler of humanity allots destiny to us.

Beowulf may indeed care what people think, as much as Diomedes does. Still, he would seem to exemplify Aristotle’s words (Nicomachean Ethics III.vi.12, 1115b4–5),

ἅμα δὲ καὶ ἀνδρίζονται ἐν οἷς ἐστὶν ἀλκὴ ἢ καλὸν τὸ ἀποθανεῖν·

Rackham and Sachs respectively have for this,

Also Courage is shown in dangers where a man can defend himself by valour or die nobly.

The courageous show courage at once in situations in which there is a defence, or in which dying is a beautiful thing.

Sachs may be more literal, but are there really two ways courage is shown? If dying is ever “a beautiful thing,” is it not when there is a defence, or there has been, and one has done one’s best to use it? Beowulf has done this, when he succumbs to the dragon’s poison.

Courage is not just fearlessness, as might be shown on a ship at sea during a storm, or for that matter on a bicycle being passed by speeding cars. All you can do then is try to stay calm. This is what Hector is doing, when he says to himself, about to face Achilles (Iliad Book XXII, lines 300–5):

Now of a surety is evil death nigh at hand, and no more afar from me, neither is there way of escape. So I ween from of old was the good pleasure of Zeus, and of the son of Zeus, the god that smiteth afar, even of them that aforetime were wont to succour me with ready hearts; but now again is my doom come upon me. Nay, but not without a struggle let me die, neither ingloriously, but in the working of some great deed for the hearing of men that are yet to be.

Hector will do his best, but is hopeless. He is like the last Roman emperor, who chose to go down fighting after the army of Sultan Mehmet II had finally breached the Theodosian Walls. By the account of Steven Runciman (The Fall of Constantinople 1453, Cambridge University, 1965, pages 139–40),

Theophilus shouted that he would rather die than live and disappeared into the oncoming hordes. Constantine himself knew now that the Empire was lost, and he had no wish to survive it. He flung off his imperial insignia and, with Don Francisco and John Dalmata still at his side, he followed Theophilus. He was never seen again.

It is one thing to expose oneself to death, like Hector and Constantine. To do that, while trying to avoid death, confident that you have a chance – this seems to be what Aristotle means by courage, and what Beowulf shows us.

It is also like the modern virtue of toleration, which Bernard Williams championed, by the account of Daniel Callcut (“Toleration is an impressive virtue that’s worth reviving,” Psyche, 6 July 2022):

Toleration involves putting up with something that you would rather not be the case …

… You might think that toleration is entirely passive, but as Williams shows, it is both active and passive. You have to actively sustain your moral beliefs at the same time as you actively resist acting on them. If you stop caring, you’d no longer be tolerant, merely indifferent.

If somebody challenges you, that person might after all be right. The spinning woman and her customer must at least tolerate one another, in order to make a deal. If a tennis match does not degenerate into an actual fight to the death, that’s toleration; your opponent may be your enemy, but only insofar as the two of you have a common measure, established by the referee.

In a proper discussion, as of some old book, the participants must be referees of themselves and one another. Are we willing

- to lay our thoughts on the table, though they may get cut to pieces?

- to listen to others’ thoughts, though they may supplant our own?

I propose to read Aristotle as raising these questions.

One Trackback

[…] Beowulf […]