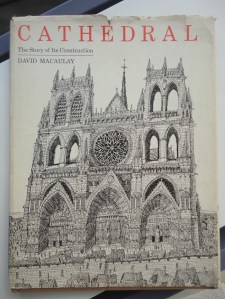

I was nine when I first read the following, and I read it many times after that:

While the windows were being installed, plasterers covered the underside of the vault and painted red lines on it to give the impression that all the stones of the web were exactly the same size. They were eager for the web to appear perfect even if no one could see the lines from the ground.

Stone cutters and sculptors finished the moldings and capitals while masons laid the stone slabs that made up the floor. They created a maze pattern in the floor. Finding one’s way to the center of the maze was considered as worthy of God’s blessing as making the long pilgrimage through the countryside that so many had to make in order to worship in a cathedral such as Chutreaux’s.

That is the text on pages 62–3 of Cathedral: The Story of Its Construction, by David Macaulay (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973). From the first paragraph, I cannot say which of two ideas impressed me more:

- faking perfection;

- not caring whether any other human saw it.

The paragraph from Cathedral is brought to mind by Claire Armitstead, “Hidden treasures,” Guardian Weekly 209 (8), 25 August 2023, online as “‘Deliberately obscure’: how to locate the weird world of hidden public art”:

In the commoditised art world, it doesn’t make sense to hide work away, yet from prehistoric cave painters to the 13th-century stonesmiths who carved gargoyles high on the spires of medieval cathedrals, artists and craftspeople have always done it – and still do.

My godfather gave me Cathedral for my birthday in 1974. In the fall, I was going to be attending school on the grounds of the Washington Cathedral; however, I don’t recall whether this was known for sure in March. I can remember taking the school’s entrance exam, but not the month when I did this. When the exam was over, I cried to a teacher that I didn’t know where I was going to find my parents; he patiently told me.

Sometime during my nine years at St Albans School, I was taken by the idea of conditioning. Maybe Brave New World did it; by the account in Wikipedia,

the novel anticipates huge scientific advancements in reproductive technology, sleep-learning, psychological manipulation and classical conditioning that are combined to make a dystopian society which is challenged by the story’s protagonist.

I don’t know whether Huxley anticipated that in 2025, computers would be assembling essays about his book, and students would think they could submit those essays to their teachers, instead of writing their own.

I must have written an essay about Brave New World, but I have no memory of it. I have my copy of the novel: it had been printed in 1978 to accompany and promote “A Universal television mini-series from NBC,” but apparently the “mini-series” was shown ultimately as one long episode. On the half-title page of my copy, I wrote a note mentioning my teacher:

Brackets with “me” beside them are mine. Other brackets indicate passages cited by Mr Reed. Hypnopaedic sayings are underlined unless I have said the line means something else.

The only example of a “hypnopaedic saying” that I find underlined now is “A gramme is better than a damn.” I can hear it in the voice of whoever said it in the TV movie (apparently Marcia Strassman).

I can trace a lot of my ideas back to parents, teachers, TV, books. How different would I be, had I never read Brave New World or Cathedral? It’s hard to say; however, it must reflect who I already was, that I have remembered

-

the latter book more than the former, and

-

more the passage I quoted above than, for example, one that I choose now at random (from page 39):

The walls of the choir were constructed in three stages. First was the arcade of piers that rose eighty feet from the foundation. Above them was the triforium, a row of arches that went up another twenty feet in front of a narrow passageway. And the last stage was the clerestory, which consisted of sixty-foot windows that reached right up to the roof.

Between 1270 and 1275 the walls of the choir and aisle were completed and work began on the roof.

I used to be able to say I could remember being two years old. Now perhaps my memories of being two have been replaced with memories of remembering it.

Six weeks after birth, I was told, my parents brought me to live in a house with a red front door. We used to drive by the house sometimes, after we had moved to another house in Alexandria, Virginia.

When asked in high school for my earliest memory, I could date it to the age of two, because that was how old I had been, when we left the House with the Red Door. As I recall now, other classmates could also remember being two. Our teacher was astonished: his memories did not go back so far.

I did not remember much about the House with the Red Door. My mother used to be astonished that I could not recall the fountain in the backyard.

From Cathedral, as I said, I remembered the idea of plastering over imperfections, even when nobody would have been able to see them anyway.

Fake perfection – fake symmetry – was on display at the Museum Van Loon in Amsterdam, when my wife and I visited in 2006. The museum was an old canal house, and I remember a room where molding for a door was at the center of a wall, but the real door was not. I didn’t have a camera then, but wrote in a travelogue,

The Van Loon is “just” a house. It has odd features, like a false doorway in a wall opposite a true one, for “symmetry.” In one bedroom, when you close the door, then the door appears to be right in the middle of one wall, directly opposite the fireplace. But the true door is shifted over a bit; you can trace out its lines. Symmetry – appearance – rules again.

I recall a book of photos of American suburban life that a friend had in his dorm room in college. In one picture, a man had sent his son up into the tree in the front yard, to pluck the few remaining brown leaves that had not yet fallen of themselves.

In my memory, the room in the Museum Van Loon is plain, at least in comparison with the rest of the house. The walls are olive drab – in my memory, which may be completely wrong. I haven’t found a photo online. I do find confirmation of the geometry of the room on Wikipedia:

The house also has fake bedroom doors: the 18th-century owners desired to have symmetry in the interior design so they painted the real bedroom doors to match the walls and fake doors to appear real in a location where one would assume a door would be.

The cited source is The Rough Guide to the Netherlands (2010). Ayşe and I used an earlier edition of this during our own visit. The book told us what to look for, and we saw it – according to my memory, at least.

I said I had recalled the painting of perfect grids of lines, on cathedral vaults that were too high to be seen from the floor. In college I found the same spirit in the “Vers dorés” of Gérard de Nerval:

Homme, libre penseur ! te crois-tu seul pensant

Dans ce monde où la vie éclate en toute chose ?

Des forces que tu tiens ta liberté dispose,

Mais de tous tes conseils l’univers est absent.Respecte dans la bête un esprit agissant :

Chaque fleur est une âme à la Nature éclose ;

Un mystère d’amour dans le métal repose ;

« Tout est sensible ! » Et tout sur ton être est puissant.Crains, dans le mur aveugle, un regard qui t’épie :

À la matière même un verbe est attaché …

Ne la fais pas servir à quelque usage impie !Souvent dans l’être obscur habite un Dieu caché ;

Et comme un œil naissant couvert par ses paupières,

Un pur esprit s’accroît sous l’écorce des pierres !

I have found an English translation, accompanied by an “Analysis” labelled “ai.” It is like the analyses that countless teachers and students must have written; the “ai” program would have been “trained” on them. The translation itself is mechanical, particularly in the title itself: not “Golden verses,” but “To Dores,” as if vers were the preposition, and dorés somebody’s name.

On another site, perhaps a human has honestly translated the poem as “Golden Lines.” This person has the eighth verse as

‘All is sentient!’ Has power over your being.

I suggest that “and all” has been forgotten between “sentient” and “has.”

There is a French analysis at a site called Superprof, with some good general advice:

Nous vous conseillons de lire le poème plusieurs fois, avec un stylo à la main qui vous permettra de noter ou souligner une découverte, une idée.

A specific analysis is then offered, apparently as a model of what one might write, more briefly, on a timed examination: the student is warned,

En outre, votre commentaire ne doit pas être aussi long que celui ici, qui a pour objectif d’être exhaustif. Vous n’aurez jamais le temps d’écrire autant !

I cut and pasted the text of “Vers dorés” above from Wikisource, where the quotation in the body is also extracted as an epigraph:

Eh quoi ! tout est sensible !

Pythagore.

The epigraph as such was omitted by editor St John Lucas in The Oxford Book of French Verse (1908). I bought my copy well-used, in Manchester, UK, when visiting my future spouse in 1997. In college, the photocopy that we used of the poem must have been from somewhere else, because the association with Pythagoras rings a bell. I have not seen the attribution justified. As for the saying itself, the closest I can find to it in Vers Dorés des Pythagoriciens, translated by Fabre-D’Olivet (Paris and Strasbourg, 1813), is the following:

Πρήξεις δ’αισχρόν ποτε μήτε μετ’ ἄλλȣ,

Μήτ’ ἰδίῃ Πάντων δὲ μάλιϛα αἰσύνεο σαυτόνEn public, en secret ne te permets jamais

Rien de mal; et surtout respecte-toi toi-même.

My transcription of the Greek includes (what I assume to be) the ligatures

Aya Kiriaki Ayazması

Holy Spring of St Kyriaki (Αγία Κυριακή)

Tarabya (Θεραπειά)

In the Loeb Classical Library volume of Early Greek Philosophy that features Pythagoras and the Pythagorean School (namely volume IV: Western Greek Thinkers, Part I), some of the spirit of Nerval’s poem may be found in fragment D13 of Pythagoras (quoted from Aëtius):

Πυθαγόρας πρῶτος ὠνόμασε τὴν τῶν ὅλων περιοχὴν κόσμον ἐκ τῆς ἐν αὐτῷ τάξεως

Pythagoras was the first to call what surrounds all things ‘kosmos’ (i.e. a beautiful organized whole) because of the order (taxis) that is found there.

The verse of the poem that impressed me the most was the ninth:

Crains, dans le mur aveugle, un regard qui t’épie.

As I would put it, the walls have eyes, though apparently, in the English saying, the walls have ears. I don’t know whether the plasterers of the vaults in the imaginary cathedral of Chutreaux would have said they were responding to such a saying.

Atsushi Miyazaki Park

Tarabya (next to Aya Kiriaki Ayazması)

I connected Nerval’s admonition also to that of Zengetsu, “a Chinese master of the T’ang dynasty,” in “No Attachment to Dust” – number 77 of the 101 Zen Stories transcribed by Senzaki and Reps and included in Zen Flesh, Zen Bones:

Even though alone in a dark room, be as if you were facing a noble guest.

There is a lot of good advice from Zengetsu, including,

A person may appear a fool and yet not be one. He may only be guarding his wisdom carefully.

Instead of telling somebody, “Bless your heart,” you can now say to him, her, or them, “You are guarding your wisdom carefully.”

Revised February 18, 2025

One Trackback

[…] be as doubtful as that of St Catherine of Alexandria. I included a winter photo of the site in “Visibility,” for no particular reason but having passed it recently. Afterwards I sent a slight correction […]