Craft is what in Greek is τέχνη: skill. One can refer to technical skill, for emphasis, or to allude to the Greek word; however, perhaps there is no skill that is not technical, and nothing technical that is not related to a skill. In that case, “technical” is just an adjective form of “skill,” and the phrase “technical skill” is a kind of polyptoton. (See footnote 1.)

In the translation by David Grene of the Philoctetes of Sophocles, “craft” is used in the pejorative sense of craftiness. The Greek is δόλος, not τέχνη; however, the latter too can have the same pejorative sense.

Odysseus is crafty. This does not just mean that he is skilful: “crafty” is an example of what Ernest Gowers calls a “worsened word.” (See footnote 2.)

Odysseus is also πολύτροπος – the Greek word here means versatile, “turning many ways,” and since that is how I may write, I have called this blog Polytropy. I think Odysseus is admirable in the Ajax of Sophocles, for wanting a decent burial for the title character, despite having been an intended victim of murder by that character. (Ajax ended up killing himself.)

In reading the Philoctetes, I incline to the side of Neoptolemus, who prefers honesty to tricks. At least, I am not good at tricks. Nonetheless, an Odysseus may be needed against the autocrats. This is what I want to look at here, using the best explanation that I have seen for the politics of today: “Populism fast and slow,” by Joseph Heath (October 20, 2025).

I read the Philoctetes for a Catherine Project community seminar on Friday, October 24, 2024.

“The” seminar comprised a number of them, at three different times of day, to accommodate as many readers as possible. Fortunately, for me at least, there was room for me in one of the seminars. I had quite enjoyed reading three other Sophocles plays – the Ajax, already mentioned, along with the Electra and The Women of Trachis – in a regular Catherine Project seminar, earlier in the fall (strictly, late in the summer too: we met on September 15, 22, and 29).

The idea of the community seminar, as I understand it, was to give new people an idea of what a seminar is, in the style of the Catherine Project or St John’s College, before committing to a slew of meetings.

In “my” meeting, at least four other participants were St John’s alumni. Maybe there were more, since I did not identify myself as a Johnnie, and maybe others didn’t either. I just said I lived about as close to the scene of the play as Athens was.

Of the fifteen participants, all told (including the leader), seven were women. Six or seven participants were outside the US: in Toronto, Mexico City, Berlin, Istanbul, Cape Town, somewhere in Brazil, and perhaps one other place. The people in Germany, Mexico, and Turkey were American. The person in Toronto was French and had read the play in French.

This all represents a benefit of global communication.

The Catherine Project has grown enough that some of its seminars are face to face. However, I’m not sure having everybody sit in the same room makes for a better seminar.

From what I have heard, a lot of local book clubs are not very serious about the readings. If instead you are strangers, meeting on line to discuss a book, then that is what you are going to do.

In any case, it is impractical to have people from all over the world come together in person to talk about a book. It is a good thing that they can come together somehow, even for the sake of the old dream of peace, love, and understanding.

I happen to be in an ongoing seminar on Faust as well. It is an unofficial, “guerrilla” seminar, for people who didn’t get into the regular Catherine Project seminar this fall. There is no leader. Two participants are German, calling in from the UK and Seoul, respectively. I confess that Sophocles’s plays seem more comprehensible than Goethe’s play, as the Iliad is more comprehensible than the Odyssey – at least to me, who could write a blog post on each book of the the former epic, twice, but not even once for the latter epic, except for the first and second books (so far).

At the beginning of the Philoctetes seminar, people said what they thought, without connecting it to what had already been said. Then we got more used to one another, and there was more interaction.

Before I started reading it for the seminar, all I could remember of the Philoctetes from college was that it took place on an island, and the title character had an infected foot.

Near the beginning of the ongoing Trojan War (apparently), Philoctetes was left on Lemnos because he had a wound that stank. Now Odysseus comes with Neoptolemus, son of Achilles, to take the bow of Philoctetes, if not the man himself. The bow is the only way that Troy will be conquered, at least according to prophecy. The prophecy is twice attributed (at lines 610 and 1339) to a captive Trojan, Helenus – a son of Priam, but we do not hear that from Sophocles.

In the seminar, one person called Philoctetes’s bow a MacGuffin. I guess that meant the bow was unimportant in itself. Somebody else agreed. Later, minds had been changed.

It sounds as if Philoctetes must also come to Troy in the flesh. However, for using the bow, Odysseus suggests (at lines 1055–9) that Teucer or even himself has the needed skill (or knowledge: ἐπιστήμη).

We can talk about the concept of prophecy. Why should we actually believe in somebody else’s prediction, especially if it is based on no argument or skill? The fact remains that the Greeks do believe. They think they need the bow of Philoctetes. In the same way, perhaps, I could think I needed a new inner tube for my bicycle, when the actual problem might be solved by a more diligent application of a patch.

For their abandonment of him, Philoctetes hates the other Greeks. He does not want to see them again. As for his bow, he needs it for hunting. The chorus of sailors point this out (lines 708–17):

No grain sown in holy earth was his, nor other food

of all enjoyed by us, men who live by labor,

save when with the feathered arrows shot by the quick bow

he got him fodder for his belly.

Ah, poor soul,

that never in ten years’ length

enjoyed a drink of wine

but looked always for the standing pools

and approached them.

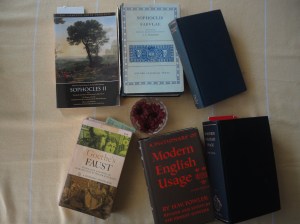

That is the David Grene translation in the Sophocles II volume of the Chicago Complete Greek Tragedies. Here in Istanbul, Pandora bookshop had the 1969 paperback edition (perhaps in a 2005 printing).

Philoctetes talks about his dependence (lines 931–3):

You robbed me of my livelihood, taking my bow.

Give it back, I beg you, give it back, I pray, my boy!

By your father’s gods, do not take my livelihood.

In the third edition, from 2013, which I have now downloaded through Anna’s Archive, the word “livelihood” has been changed to “life” in the two instances above. The Greek is βίος, as in “biology”:

ἀπεστέρηκας τὸν βίον τὰ τόξ᾽ ἑλών.

ἀπόδος, ἱκνοῦμαί σ᾽, ἀπόδος, ἱκετεύω, τέκνον·

πρὸς θεῶν πατρῴων, τὸν βίον με μὴ ἀφέλῃς.

In both passages quoted so far, “bow” is τόξον, as in those sayings of Heraclitus (B51 and B48 in Diels and Kranz; D49 and D53 in the Loeb volume, Early Greek Philosophy III, edited and translated by Laks and Most):

οὐ ξυνιᾶσιν ὅκως

διαφερόμενον ἑωυτῷ ὁμολογέει·

παλίντροπος ἁρμονίη

ὅκωσπερ τόξου καὶ λύρης.They do not comprehend how,

diverging, it accords with itself:

a backward-turning fitting-together (harmoniê),

as of a bow and a lyre.τῷ οὖν τόξῳ ὄνομα βίος,

ἔργον δὲ θάνατος.The name of the bow (cf. biós) is life (bíos),

but its work is death.

As the gloss in the English suggests, another Greek word for bow is βιός. Fortunately, perhaps, nobody brought this up in the seminar, because it is a piece of expert knowledge not shared by the group.

Somebody did start talking about the Iliad. If he had gone on much longer, I think the moderator would rightly have stopped him, since unfortunately one cannot assume that everybody has read Homer. Even if we had all read the Iliad, we should probably focus on the work at hand.

Does that mean we should not make connections with our own life? The person who brought up the Iliad talked about the Greek sense of honor. I wanted to ask whether we had a sense of honor.

A key theme of the Philoctetes arises in lines 100–3. In the third Chicago edition (edited by Griffith and Most), those lines are as follows.

- NEOPTOLEMUS

- What do you tell me to do, except tell lies?

- ODYSSEUS

- I’m telling you to use a trick to take Philoctetes.

- NEOPTOLEMUS

- And why must I use a trick, rather than persuasion?

- ODYSSEUS

- He will not be persuaded, and force will fail.

Perhaps that version is clearer to today’s students than Grene’s original:

- NEOPTOLEMUS

- What do you bid me do, but to tell lies?

- ODYSSEUS

- By craft I bid you take him, Philoctetes.

- NEOPTOLEMUS

- And why by craft rather than persuasion?

- ODYSSEUS

- He will not be persuaded; force will fail.

Green’s word “craft” sent me to the SOPHOCLIS FABVLAE (edited by Pearson) of the SCRIPTORVM CLASSICORVM BIBLIOTHECA OXONIENSIS. The Greek was not the τέχνη, as in “technical,” that I knew, but δόλος, which I did not. It seems there is a Latin word dolus with the same sense, forming part of “sedulous,” meaning without deceit, thus zealous; and δολερός “deceitful” gives us dolerite, a rock easily confused with diorite.

“Craft” is ambiguous; is it skill, or deviousness? The ambiguity is possessed also by τέχνη. The chorus use that word, when talking to Philoctetes about Odysseus; Grene translates it as “cunning,” after again translating δόλος as “craft” (lines 133–40):

- ODYSSEUS

May Hermes, God of Craft, the Guide, for us

be guide indeed, and Victory and Athene,

the City Goddess, who preserves me ever.(Exit Odysseus)

- CHORUS

Sir, we are strangers, and this land is strange;

what shall we say and what conceal from this suspicious man?

Tell us.

For cunning that passes another’s cunning

and a pre-eminent judgment lie with the prince,

in whose sovereign keeping is Zeus’s holy sceptre.

It does not seem as if knowing any Greek really opens up any secrets here. We can observe in English that a skill can be used or misused. Is it a misuse, if somebody is deceived?

Vladimir Putin has a double: the rumors are true. At least, this is the judgment of Claire Berlinski’s old Oxford classmate Christopher Alexander, who, as a Canadian diplomat, spent a fair amount of time talking with Putin in Russian – as I was reading recently.

Probably there is something wrong with using skill in plastic surgery to make somebody look like somebody else. However, maybe it has to be done sometimes. As Odysseus says in the Philoctetes (line 1049),

οὗ γὰρ τοιούτων δεῖ, τοιοῦτός εἰμ’ ἐγώ.

Whatever is needed, that’s what I am.

That’s my translation; Grene’s is,

As the occasion demands, such a one am I.

I have to ask: How do you know what is needed? How do you decide between conflicting demands? Neoptolemus has to answer that for himself.

The Oxford Classical Text that I have been consulting: I have the copy that my friend gave me, after graduation from St John’s, because he figured I would have more use for it than he. Perhaps he was right, even though I could have consulted instead the Perseus Project site, which I have in fact used for cutting and pasting into this post. Here are those key verses 100–3, laying out those alternatives of

- lying (ψευδῆ λέγω) or craft (δόλος),

- persuading (πείθω), and

- force (βία) (see footnote 3):

- Νεοπτόλεμος

- τί μ᾽ οὖν ἄνωγας ἄλλο πλὴν ψευδῆ λέγειν;

- Ὀδυσσεύς

- λέγω σ᾽ ἐγὼ δόλῳ Φιλοκτήτην λαβεῖν.

- Νεοπτόλεμος

- τί δ᾽ ἐν δόλῳ δεῖ μᾶλλον ἢ πείσαντ᾽ ἄγειν;

- Ὀδυσσεύς

- οὐ μὴ πίθηται· πρὸς βίαν δ᾽ οὐκ ἂν λάβοις.

I prefer persuasion. This may put me at a disadvantage, which is described by another Canadian who has been brought to my attention by Claire Berlinski. Getting at the truth of things requires more work than most people want to do. What’s more important then, the truth or the people?

… academics have not done a great job confronting the most confounding aspect of populism, which is that the more it gets criticized by intellectuals, the more powerful it becomes.

Thus Joseph Heath in “Populism fast and slow” (October 20, 2025).

It is a fascinating essay, but dismaying, if only by laying out so clearly, to my mind at least, why (for example) so many Americans can now forget the founding principle that all of us are created equal.

Do I really think we are all created equal? The Noble Lie in the Republic is that we are forged underground from different metals; but the key point then is that once we are above ground, there is no telling which metal is ours. It cannot automatically be inferred from our lineage.

It might be revealed by aptitude tests. At least, that is what the Platonic Socrates seems to think. In school, we get distinguished by such tests, which traumatize many of us.

… it is not difficult to see why populism can be an effective political strategy … an acceleration in the pace of communication favours intuitive over analytical thinking. Populists will always have the best 30-second TV commercials …

… People are not rebelling against economic elites, but rather against cognitive elites. Narrowly construed, it is a rebellion against executive function. More generally, it is a rebellion against modern society, which requires the ceaseless exercise of cognitive inhibition and control, in order to evade exploitation, marginalization, addiction, and stigma. Elites have basically rigged all of society so that, increasingly, one must deploy the cognitive skills possessed by elites to successfully navigate the social world.

Persons such as the current rulers of Turkey, Russia, Hungary, and the United States have another kind of skill – or perhaps we should call it craft. Odysseus has it too then; and yet, in the Philoctetes, he would seem to put it to use, not for himself, and not for all of humanity either, but at least for all of the Greeks. If he succeeds, then other Greeks will have the honor of defeating Troy.

Atatürk Arboretum

Bahçeköy, Sarıyer, Istanbul

Tuesday, October 21, 2025

Notes

-

I do not recall hearing of the polyptoton before. The Oxford English Dictionary tags the word as “not naturalized.” It is not in the dictionary of “Some Grammatical and Rhetorical Figures” (from anacoluthon to zeugma) that Smyth includes in his Greek Grammar (pages 671–83). I learned of the word “polyptoton” as I had hoped to, by looking up the related figure of the cognate object on Wikipedia. One can understand polyptoton as the use of multiple cases of the same word, since the Greek word for grammatical case is πτώσις – as I confirmed by checking the handy list of Yunanca Gramer Terimleri, at the end of the Greek-Turkish edition of Dionysios Thraks, ΤΕΧΝΗ ΓΡΑΜΜΑΤΙΚΗ / Gramer Sanatı, edited by Eyüp Çoraklı (Istanbul: Kabalcı, 2006). In English, ptosis is the drooping of an eyelid or other body part. I suggest that “technical skill” is a case of polyptoton, even though “technical” and “skill” are not related in form. They are related, because “technical” = “skilled,” and thus the words are cognate in a broad sense – a sense that I probably learned from H. W. Fowler in A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1926):

cognate (Gram.); ‘akin’. A noun that expresses again, with or without some limitation, the action of a verb to which it is appended in a sentence is distinguished from the direct object of a transitive verb (expressing the external person or thing on which the action is exerted) as the cognate, or the internal, or the adverbial, object or accusative:

- is playing whist (cognate);

- I hate whist (direct);

- lived a good life (internal or cognate);

- spent his life well (direct);

- looked daggers (adverbial or cognate).

In the last example daggers is a metaphor for a look of a certain kind, & therefore cognate with the verb.

To argue against Fowler here, because the word “daggers” has no historical connection with “look,” would be a kind of etymological fallacy. Perhaps there was no example of a properly transitive use of “look” for Fowler to include, although there are copulatory uses, as in “look sharp” (be sharp in appearance).

-

I had not realized until now that, in the second edition (1965) of A Dictionary of Modern English Usage, the article “Worsened words” was created by the editor, Ernest Gowers. It seems of a piece with Fowler’s own general articles, such as “Battered ornaments,” “Out of the frying-pan,” and “Pairs and snares.” Gowers’s examples of worsened words are in three groups.

-

Discussed in the article:

- imperialism,

- colonialism,

- bourgeois,

- capitalist,

- appeasement,

- epithet,

- collaborator,

- academic,

- hypothesis,

- pop singer,

- reactionary.

-

“Seldom used by educated people except on a note of parody”:

- buxom,

- gallant,

- genteel,

- intrepid,

- sinful,

- virtuous,

- winsome.

-

Worsened in the past:

- candid,

- commonplace,

- crafty,

- garble,

- egregious,

- idiot,

- indifferent,

- knave,

- leer,

- lewd,

- -monger compounds,

- officious,

- plausible,

- prevent,

- purlieu,

- respectable,

- rhetoric,

- sensual,

- silly,

- specious,

- villain,

- worthy.

Of the words that I have bolded, in addition to the one to which this note is attached, Gowers says,

Not until the 1933 supplement appeared did the OED contain any suggestion that academic could be used in a derogatory sense, reflecting the view, widely held today, that acquiring knowledge is a waste of time unless it is a means of material advancement. Hypothesis seems to be going the same way. ‘Today’, says Medawar, ‘the pejorative use of hypothesis (Evolution is only an h.; It’s only an h. that smoking causes lung cancer) is a sign of semi-literacy.’

I’m guessing Medawar is biologist Peter Medawar. Populism has long been at work. “Populism” itself is a worsened word, by the account of Thomas Frank.

-

-

For Beekes, the IE root of

- βία “strength, force” is *gwei- “conquer, force”;

- βιός “bow, bowstring” is *gwieh2– “string”;

- βιω- “to live” is *gweih3– “live”;

- ἥβη “youth, prime, vigour of youth, sexual maturity” is possibly *(H)iēgw‑eh2– “youth, (youthful) vigour.”

I could see no suggestion of a relation between any two of these roots, even though derived words might seem to be “cognate” in the broad sense of footnote 1. For the Linguistics Research Center at UT Austin, the roots are:

- gueiə- “to prevail, overpower, be mighty” (with English cognates “Jain” and “quench”);

- guheiə- : guhī- “vein, sinew, tendon” (“file,” “filament”;

- guei-, and gueiə- “to live, survive” (“quick,” “survive”);

- iēguā “force, strength”; (“ephebe”).

As for “craft,” it does not seem to have been traced further back than the Germanic family. Apparently the original sense of power remains in German Kraft, so that the name of the band Kraftwerk refers not to craftwork but a power plant.

Edited November 4, 2025, and March 9, 2026

3 Trackbacks

[…] « Craft and Craftiness […]

[…] the post before last, “Craft and Craftiness,” I mentioned finding the Philoctetes of Sophocles more comprehensible than Faust. I had an […]

[…] Sophocles, Philoctetes. […]