By the account of Chapter XXX, called “War as the Breakdown of Policy,” of Collingwood’s New Leviathan (1942), humans have not always made war (30. 1). Why then do we make it now? People say war is a continuation of policy (30. 14); but as Collingwood cleverly points out (30. 15), the original saying, which is due to Clausewitz (30. 69), is ambiguous: a continuation could be an extension or a breakdown (30. 16–17).

-

-

Meta

-

Archives

-

Categories

- Art (185)

- Music (3)

- Poetry (107)

- Homer (75)

- Sylvia Plath (4)

- T. S. Eliot (12)

- Prose (71)

- Visual Art (26)

- Film (5)

- Education (54)

- Facebook (14)

- History (66)

- Archeology (6)

- Tourism (30)

- Language (35)

- Fowler (6)

- Grammar (12)

- Strunk and White (9)

- Turkish (7)

- Logic (12)

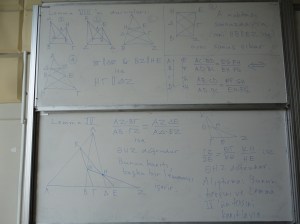

- Mathematics (76)

- Exposition (20)

- Mathematical Topics (10)

- Calculus (4)

- Conic Sections (6)

- Mathematicians (28)

- Archimedes (8)

- Euclid (20)

- G. H. Hardy (7)

- Philosophy of Mathematics (18)

- Nature (27)

- Philosophy (296)

- “God is a circle …” (5)

- Categorical Thinking (6)

- Causation (12)

- Contradiction (8)

- Criteriological Science (8)

- dialectic (28)

- Freedom (23)

- Ontological Proof (6)

- Pacifism (9)

- Persons (243)

- Aristotle (59)

- Collingwood (164)

- absolute presuppositions (18)

- “ceases to be a mind” (5)

- New Leviathan (70)

- overlap of classes (11)

- Principles of Art (46)

- question and answer (5)

- Descartes (18)

- Leo Strauss (11)

- Midgley (13)

- Pirsig (38)

- Plato (100)

- Philosophy of History (27)

- Sex and Gender (12)

- Stoicism (2)

- Psychology (19)

- Science (30)

- Galileo (7)

- Turkey (98)

- coup (3)

- Istanbul (59)

- Bosphorus (5)

- Gezi (8)

- The Islands (3)

- Tophane (3)

- Nesin Mathematics Village (27)

- Uncategorized (8)

- West Virginia (16)

- Art (185)

-

Recent Posts