Remarkable teachings from the Franklin, who says he never learned rhetoric, nor read Cicero:

Pacience is an heigh vertu certeyn;

For it venquisseth, as thise clerkes seyn,

Thinges that rigour sholde never atteyne.Patience is a high virtue certain;

For it vanquisheth, as these clerks say,

Things that rigor should never attain.

There are things that you cannot win by force. Love is one, and that is the Franklin’s theme.

You can’t hurry love

No you just have to wait

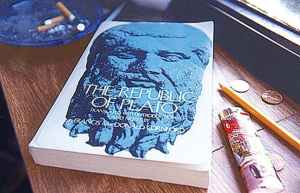

Respect is another thing that you cannot win by force. I took up that theme in considering Collingwood on “Civilization as Education” (September, 2018). Confusion here may explain the problem of bad leadership that Socrates takes up in the Republic – which I have now taken up in a new series.

Rembrandt van Rijn

Lucretia, 1664

Andrew W. Mellon Collection

National Gallery of Art, Washington