Between the composing of parts 1 and 2 of this account came the death of Prince, whose work had inspired Rain the Color of Blue with a Little Red in It. Between the composing of parts 2 and 3 came the release of the four Turkish peace activists, whose imprisonment had given poignancy to The Demons and The Music of Strangers. There is a certain absurdity associated with each event.

Nikkyô Niwano, Shakyamuni Buddha: A Narrative Biography

(Tokyo: Kôsei Publishing Co., 1980; fifth printing, 1989)

On the cover, a modern copy by Ryûsen Miyahara,

owned by Risshô Kôsei-kai, of

“The Nirvana of the Buddha,”

painted in 1086 and owned by temple Kongôbu-ji,

Wakayama Prefecture, Japan

-

The cult of celebrity is absurd. I say this as somebody who did not know that Lady Diana had died until two days later, when I happened to notice a newspaper headline on the street. This was in Urbana, Illinois, in the company of a British person who, sixteen years earlier, had gone out for a walk when the royal wedding of Charles and Diana came on the telly. I currently keep in touch with the latest events through Twitter, where my main focus is news of Turkey. I have seen some tweets of mourning for Prince. If there is elaborate mourning going on, as for Diana, I call it absurd. If you are devoted to an artist, I think what this means is that the artist lives in you. Reincarnation happens this way. I like the paintings of the death of the Buddha, in which the contortions in the faces of his followers are inversely proportional to their level of enlightenment. Sages observe the death-bed scene with equanimity.

-

It is absurd that four people were held in prison in Turkey for forty days, pending trial for spreading propaganda for a terrorist organization; and then, when the trial happened, the prosecutor changed his mind and wanted to charge the four with insulting the Turkish state instead.

The four had been charged with terrorist propaganda for spreading a petition that called on the Turkish government to make peace with Kurdish rebels. The petition did not call on the rebels themselves to make peace: this was evidence that the signers were in league with the rebels. As the four pointed out to the judge, they were addressing their own government; it was not for them to enter into communication with rebels, particularly rebels considered terrorist by the state. Moreover, as academics, they had not studied for years, just to take orders from somebody else. This is a fine defense; but it is absurd that the defense needs making.

The prosecutor needs permission from the Justice Ministry to pursue the new charge of insulting the state. While permission is being sought, the four prisoners are free. That is great for them, their families, their students, and us, their colleagues and friends. I do not otherwise feel like celebrating.

India gave the world Siddharta Gautama, the Buddha. Turkey has given us Nasreddin Hodja, the thirteenth-century Sufi sage. A family complained to Hodja that their house was too small. Hodja recommended that they bring their farm animals into the house to live. It did not make any sense, but the family gave it a try. Conditions became worse than before. After a trial period, the family went back to Hodja to complain.

“Take the animals out of your house,” suggested Hodja.

The family did this, with tremendous relief, for which they thanked Hodja profusely.

I may feel relief, but I do not feel thankful at the undoing of what should not have been done in the first place.

Interruption

Yorgos Zois. Greece France, and Croatia. Greek. Beyoğlu, Saturday, April 16, 2016, 13:30

Beowulf,

translated by Michael Alexander

(Penguin, 1973, reprinted 1977)

The Beowulf Manuscript,

edited and translated by R. D. Fulk

(Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library, 2010)

In the winter following my graduation from St John’s College, the National Gallery of Art had an exhibit of pre-classical Greek art. Better than the archaic sculptures themselves, I remember the accompanying series of Greek dramas on film. I was impressed by Pasolini’s version of Oedipus Rex, as well as by a version of the Agamemnon in which men played all roles, as they would have in Athens, and in which the Greek was translated so as to resemble Old English—not the language of Shakespeare, but of Beowulf. This could mean use of alliteration and of kennings, such as “whale road” (hron rade) for the sea. I take the example from the first page (and my notes from school thereon) of the Penguin translation that I read in the tenth grade; the original Old English is from the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library edition. From the Agamemnon film, I seem to recall the term “blood grudge,” which is alliterative or a kenning only in a broad sense, but which may serve as an example of what the translators were trying to achieve.

In December of 2012, from Pandora Bookshop here in Istanbul I bought the English translation of Alain Badiou’s French “hyper-translation” of Plato’s Republic. Being a hyper-translation means being translated into our times. Glaucon’s brother Adeimantus is replaced by a sister, Amantha; references to Marx are allowed.

Aeschylus, Oresteia,

translated and with an Introduction by Richmond Lattimore

(University of Chicago Press, 1953)

Aeschylus, The Oresteian Trilogy, translated by Philip Vellacott

(Penguin, 1956, reprinted 1978)

The film Interruption is a hyper-translation of the Agamemnon, or rather of the whole Orestia trilogy. It starts as a film of a modern-dress adaptation of the Agamemnon. The stage is bare, but for glowing tubes that frame a cube, which is to be understood as the Palace of Atreus. A man with a microphone comes on stage, says he represents the chorus, and announces that the play will proceed with audience participation.

In a book of manly advice for boys, I once saw the assertion that men with beards have something to hide. In Interruption, I took the chorus leader’s clean-shaven visage as a sign of evil. At any rate, he gave me the creeps, and I assume he was supposed to. He induces interested parties to come forward from the audience. The men among them wear beards. The chorus leader, now master of ceremonies, sits in the audience and interrogates the the new participants in the drama.

Things proceed from there. I cannot remember the exact sequence. Chairs are brought out, and the new players are invited to sit and discuss the Oresteia, as if they were in a seminar at St John’s College. What is the relevance for today of the ancient myths? Would the new players advise Orestes to kill his mother? This is still in the first half of the film.

The movie is one example where I am sorry to have read the catalogue synopsis beforehand, because it caused me to expect things that never happened. According to the synopsis,

Director Yorgos Zois states that Interruption is a film that is inspired from a real-life hostage situation without the hostages realizing it.

Did this mean that, in the story of the movie, the audience in the theater were going to be held for ransom, or their cars or flats were going to be ransacked while the audience themselves were distracted by the unusual play? If such a question is going to be raised, I would rather it be done by the movie itself.

Since I have now raised the question myself, I shall say that the answer is no. Still the film is ambiguous. One does not know whether everything that happens on stage is an act. One does not know whether all of the volunteers from the audience are really volunteers. One wonders whether the property pistol can really fire a bullet.

It is inspiring that Greece has the ancient myths to draw on. We all have the Greek myths, whatever country we are from; and even modern Greece must translate the old texts into its current language, even as Anglophone countries must translate Beowulf. But if you are Greek, the judgment of Orestes takes place in your own country’s capital.

We may think today that Orestes has no right to kill his mother, regardless of her having killed his father. Revenge is obsolete. And yet Turkish judges seem still to recognize honor as a mitigating factor when women are murdered by their families.

The Constitution of the United States of America

(Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1976)

The Oresteia represents the world’s first trial by jury. In discussing Rain the Color of Blue with a Little Red in It, I mentioned a graduate-school office-mate who was embarrassed by Prince. Another office-mate was applying for American citizenship, but the jury system did not make sense to her. She thought experts should decide cases. Emei was from Hong Kong, which was still British; so I suppose the British had never introduced jury trials. I told Emei that trial by jury was our right as Americans; we could waive it if we wanted! Meanwhile, here it is, as Amendment VI of the Constitution, originally Article VI of the Bill of Rights:

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defence.

Add to this a clause from Article V:

nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb.

If you are accused of a crime, and a jury finds you innocent, you are free. If you are found guilty, but you think the jury was unfair, you can appeal to a higher court. It seems like a great system to me. If you object that the people cannot be trusted to sit on juries, then how can you trust them to vote for a government? Indeed, how can you justify their vote, if they should happen to elect you?

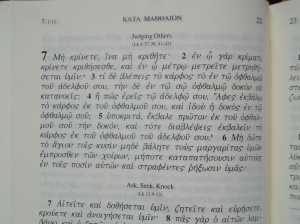

Democracy is more than voting. It is more than having a free press through which you can be informed about candidates. Democracy is participation in governing, and one way of doing this is sitting on a jury. As a graduate student, I was called for jury duty in Prince George’s County, Maryland. As I got off the bus in the county seat of Upper Marlboro, so did another new juror, who remarked on how scared she was. I don’t know if this was the same kind of fear that keeps people from visiting art museums. Perhaps the fear is related to a shame of ignorance that is created in school. Apparently some Christians object to sitting in judgment of their fellow sinners. Their objections may stem from the words of Jesus of Nazareth in the Sermon on the Mount, as reported by Matthew and translated by the scholars appointed by King James in 1611:

Judge not, that ye be not judged.

For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged: and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again.

And why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?

Or wilt thou say to thy brother, Let me pull out the mote out of thine eye; and behold, a beam is in thine own eye?

Thou hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then shalt thou see clearly to cast out the mote out of thine own eye.

Paraphrased, this goes:

Do not judge others, so that God will not judge you—because God will judge you in the same way you judge others, and he will apply to you the same rules you apply to others. Why, then, do you look at the speck in your brother’s eye, and pay no attention to the log in your own eye? How dare you say to your brother, “Please, let me take that speck out of your eye,” when you have a log in your own eye? You hypocrite! Take the log out of your own eye first, and then you will be able to see and take the speck out of your brother’s eye.

This is fine advice; but in a democracy, one is sometimes called on to be a judge. To refuse the call is itself to make a judgment.

Good News for Modern Man: The New Testament in Today’s English Version

(Third Edition; New York: American Bible Society, 1971)

The Greek New Testament

(Fourth Revised Edition; Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2001)

The Bible: Authorized King James Version with Apocrypha

(Oxford World Classics, 2008)

Unfortunately the jury system has eroded in the United States through plea agreements. Those accused of crimes agree to accept a certain punishment, on the threat that a jury trial could give them a greater punishment. Apparently it is held to be in the interest of the state to avoid the expense of a jury trial. But justice is the true interest of the state, insofar as it represents the people. A part of justice is the democratic education of the citizens, through serving on juries.

I cannot say that all of this was a theme intended by the director of Interruption. But the lives of our colleague Kıvanç and others had been interrupted by their imprisonment. Their fate was to be decided by a state-appointed judge, not a jury of their peers. A vengeful president had already given his opinion of the imprisoned, and of the thousand other academics who called for peace: those who support terrorist organizations ought to be stripped of citizenship (as reported by the state-run Anadolu Agency, April 5, 2016). Interruption was an occasion to consider the justice of this.

Under the Sun

Vitaly Mansky. Czech Republic, Russia, Germany, North Korea, and Latvia. Korean. Fitaş 6, Saturday, April 16, 2016, 16:00

We saw Under the Sun because it was from North Korea. It was supposedly made with the approval of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea; but later, outside the country (presumably), captions were added, explaining government demands, and the government did not like the end result. Perhaps supposed to be a film about the patriotic zeal of a girl in Pyongyang, the film ends up being about the very making of such a film. We see the girl eating at home with her parents—and then we see a local director telling the trio to try again, with dialogue like the following (which I recall approximately):

“You should eat 100g of kimchee a day!”

“Yes, kimchee provides vitamins and helps prevent cancer!”

“Ha ha, you are so smart! That is because you read so many books!”

The girl’s mother works with other women in a soy milk plant; her father is an engineer at a garment factory, where women do the actual sewing. At the soy dairy, the workers are told that the people like their product so much, they will have to produce more. The local director tells the workers to smile more enthusiastically when they hear this. They should also congratulate our girl’s mother for her daughter’s induction in the Youth Corps. At the garment factory, a sewer is awarded for productivity; all of the workers are reminded to look cheerful.

It was probably in my political geography class in 1978–9 that I read a book about China, which captioned a photo of a crowd marching past the camera with the observation that people smiled only as they neared the camera, because they were being ordered to do so. Thus were Chinese propaganda pictures explained to the American student. The explanation itself could have been Cold-War propaganda on the part of the book’s authors. I remember pointing out to my teacher that in our own textbook, in the chapter on the Soviet Union, most of the photographs were black and white, while the other chapters were more colorful.

In Under the Sun, we have a director from the former Soviet Union documenting propaganda techniques of North Korea, with the approval of the regime. Thus we are shown a classroom of little girls. A young woman instructs them on the evils of the landlords and the Japanese, who were overthrown by Kim Il-sung. The pupils are young; the lesson, simple and repetitive. Kim Il-sung saw the nasty Japanese in a boat, and so he picked up a stone and destroyed them with it.

The time of year is early spring. In the classroom, we can see the breath of the girls as they repeat their lessons. No fuel is wasted on heat. Outside, on the broad avenues, there is little traffic, and most of it is busses. This could be an environmentalist utopia. The example of North Korea can save the world. Photos from the International Space Station show Japan, China, and South Korea all lit up at night, while North Korea is dark. Why send light off into space? We should all be as thrifty as the North Koreans. But it ought to be by informed choice.

In the documentary, the streets of Pyongyang are clean, presumably in part because there is little production of wasteful packaging. But there is a brief scene of a trashcan being picked through by urchins.

We see also piles of bouquets left by devoted citizens at an altar to the deified Eternal President of North Korea. At her death, Princess Diana must not have received so many flowers as the late Kim Il-sung does in any one year on the Day of the Sun, which commemorates his birth. After the ceremonies, workers throw the flowers in bins.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk was deified in Turkey. His picture was in every classroom, and if a foreign teacher joked about this, he would receive a visit from the police. By the account of one such teacher (The Yogurt Man Cometh, which I lent out and never got back), if he and his foreign colleagues wanted to talk freely about the ubiquity of Atatürk’s image, they referred to the man as Fred. Official visitors to the mausoleum of Atatürk are supposed to write to him in a book reserved for this purpose. When I was at METU, and the faculty wanted to protest the government, we marched to the mausoleum in order to share our complaint with Atatürk.

However, unlike Kim Il-sung, Atatürk founded no dynasty. The current President despises him, for his suppression of religion or simply for being an object of adulation in competition with himself. It is a fashion among some Turks today to have a decal of Atatürk’s signature on their car or motorcycle, or to have that signature tatooed on their forearm. But the official cult of Atatürk seems to have been largely overthrown. In North Korea, the paired images of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il are everywhere, while schoolchildren are told how much they are loved by the deity’s current incarnation, Kim Jong-un.

News from Planet Mars

Dominik Moll. France and Belgium. French. Fitaş 4, Sunday, April 17, 2016, 13:30

I pair News from Planet Mars with Florida for being an entertaining take on problems of contemporary life in western Europe. In News from Planet Mars, the problem is dealing with other people’s shit, be it that of your former spouse, your children, your sibling—or your neighbor’s dog. Philippe Mars tells his neighbor to clean up after the beast. The neighbor says he has enough problems, and Mars should not be so uptight; why doesn’t he just go fuck his wife, or, since he hasn’t got one, jerk off?

Mars’s mild manners are given one test after the other. Hix ex-wife will not do her share of child-minding. His son becomes a vegan. His daughter won’t leave off studying in her room, even to celebrate his birthday. His ear is cut off by his psychotic co-worker, who then escapes from the psycho ward and talks his way into sleeping on Philippe’s couch. Then Jérôme gets Philippe to let his love interest from the psycho ward sleep in Philippe’s bed. And that is not all; but it all ends happily as Chloé overcomes her aversion to being touched, and she and Jérôme tramp off towards the Belgian border after a failed attempt at blowing up a planned chicken factory.

To break the monotony of chronological narration, Florida used flashbacks. News from Planet Mars uses the image of Philippe Mars as an astronaut coming down to observe life on earth. It also uses the ghosts of Philippe’s late parents, who remind him that children have always driven their parents crazy.

W. Somerset Maugham, Three Early Novels:

Liza of Lambeth [1897], Mrs Craddock [1902], The Magician [1908]

(New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2005)

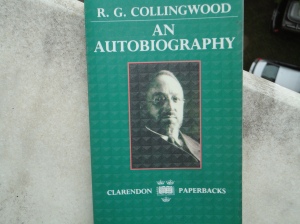

Movies like this put me in mind of a passage that I remember from Somerset Maugham’s Mrs Craddock. In her reading, the title character finds herself among old books: not just the classics, but also the books that were written entirely for their time. This would need some explanation, if one is inclined to agree with Collingwood (as I am) when he says in his Autobiography (page 39),

writers (at any rate good writers) always write for their contemporaries, and in particular for those who are ‘likely to be interested’, which means those who are already asking the question to which an answer is being offered; and consequently a writer very seldom explains what the question is that he is trying to answer.

Jane Austen wrote for her time, but turned out to have written classics. There is however writing that does not stand the test of time, for no fault of its own; and this is how I imagine News from Planet Mars. It was written for today, and it was thus a fine way to end our watching of festival films.

The actual passage of Maugham is richer than I had remembered. It is from the antepenultimate chapter of Mrs Craddock:

She began to read with greater zest, and in her favourite seat, on the sofa by the window, spent long hours of pleasure. She read as fancy prompted her, without a plan, because she wanted to, and not because she ought. She obtained pleasure by contrasting different writers, getting emotions out of the gravity of one and the frivolity of the next. She went from the latest novel to Orlando Furioso, from the Euphues of John Lyly (most entertaining and whimsical of books) to the tender melancholy of Verlaine. With a lifetime before her, the length of books was no hindrance, and she started boldly upon the eight volumes of the Decline and Fall, upon the many tomes of St Simon; and she never hesitated to put them aside after a hundred pages.

Bertha found reality tolerable when it was merely a background, a foil to the fantastic happenings of old books: she looked at the green trees, and the song of birds mingled agreeably with her thoughts, still occupied with the Dolorous Knight of La Mancha, with Manon Lescaut or the joyous band that wanders through the Decameron. With greater knowledge came greater curiosity, and she forsook the broad high-roads of literature for the mountain pathways of some obscure poet, for the bridle-track of the Spanish picaroon. She found unexpected satisfaction in the half-forgotten masterpieces of the past, in poets not quite divine whom fashion had left to one side, in the playwrights, novelists and essayists whose remembrance lives only with the bookworm. It is a relief sometimes to look away from the bright sun of perfect achievement; and the writers who appealed to their age and not to posterity have by contrast a subtle charm. Undazzled by their splendour, one may discern more easily their individualities and the spirit of their time; they have pleasant qualities not always found among their betters, and there is even a certain pathos in their incomplete success.

I saw only recent films in the festival; but there were older ones. News from Planet Mars and Florida were like the writers who appeal to their age, in Maugham’s sympathetic account.

3 Trackbacks

[…] « 35th Istanbul Film Festival, 2016 35th Istanbul Film Festival, 2016, part 3 » […]

[…] Part 3: […]

[…] from Planet Mars, about the problem of dealing with other people’s shit. I wrote about it in “35th Istanbul Film Festival, 2016, part 3.” I enjoyed it, but thought it would not be a classic; it was like the work of writers whom […]