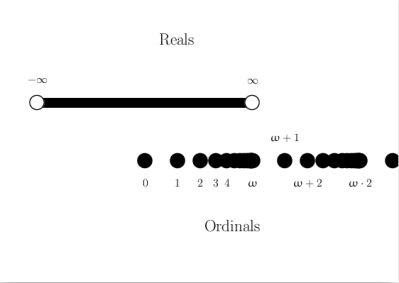

This is a little about mathematics, and a little about writing for the web, but mostly about the nuts and bolts of putting mathematics on the web. I want to record how, mainly with the pandoc program, I have converted some mathematics from a LaTeX file into html. Like “Computer Recovery” then, this post is a laboratory notebook.

-

-

Meta

-

Archives

-

Categories

- Art (185)

- Music (3)

- Poetry (107)

- Homer (75)

- Sylvia Plath (4)

- T. S. Eliot (12)

- Prose (71)

- Visual Art (26)

- Film (5)

- Education (54)

- Facebook (14)

- History (66)

- Archeology (6)

- Tourism (30)

- Language (35)

- Fowler (6)

- Grammar (12)

- Strunk and White (9)

- Turkish (7)

- Logic (12)

- Mathematics (76)

- Exposition (20)

- Mathematical Topics (10)

- Calculus (4)

- Conic Sections (6)

- Mathematicians (28)

- Archimedes (8)

- Euclid (20)

- G. H. Hardy (7)

- Philosophy of Mathematics (18)

- Nature (27)

- Philosophy (296)

- “God is a circle …” (5)

- Categorical Thinking (6)

- Causation (12)

- Contradiction (8)

- Criteriological Science (8)

- dialectic (28)

- Freedom (23)

- Ontological Proof (6)

- Pacifism (9)

- Persons (243)

- Aristotle (59)

- Collingwood (164)

- absolute presuppositions (18)

- “ceases to be a mind” (5)

- New Leviathan (70)

- overlap of classes (11)

- Principles of Art (46)

- question and answer (5)

- Descartes (18)

- Leo Strauss (11)

- Midgley (13)

- Pirsig (38)

- Plato (100)

- Philosophy of History (27)

- Sex and Gender (12)

- Stoicism (2)

- Psychology (19)

- Science (30)

- Galileo (7)

- Turkey (98)

- coup (3)

- Istanbul (59)

- Bosphorus (5)

- Gezi (8)

- The Islands (3)

- Tophane (3)

- Nesin Mathematics Village (27)

- Uncategorized (8)

- West Virginia (16)

- Art (185)

-

Recent Posts