Although the word telezzüz is absent from one Turkish dictionary (Arkadaş Türkçe Sözlük, 2004), I find it in a couple of Turkish-English dictionaries. Its length recalls Ottoman times, when Turkish speakers freely borrowed from Persian and Arabic.

Native Turkish words can be extended to great length with grammatical endings, as in gelemeyebilirim. I once heard a taxi driver say that to a colleague who was making tea. He was saying literally, “I am able to be unable to come”; he meant, “Maybe I can’t come have tea, because I’ve got to take this guy out to the airport.” The single word for all of that was built up from the single syllable gel- “come” by addition of -eme- “be unable,” -y- (buffer), -ebil- “be able,” -ir- (marking an aorist verb), and -im “I.” By contrast, telezzüz has no such analysis, at least not in Turkish. This brands the word as foreign, at least to my understanding, the way sesquipedality in an English word connotes a borrowing from Latin or Greek.

As I have just learned, the word telezzüz is used as the name of an upscale vegetarian restaurant, over on the Asian side of Istanbul, near an Ottoman kiosk that my wife and I have visited. Perhaps one day we will dine at the restaurant, for a taste of luxury, the way we dined at Nicole, in European Istanbul, almost nine years ago. Unfortunately, for us at least, that restaurant wasn’t vegetarian.

Homemade pizza with asparagus from Elibelinde

Tuesday, May 21, 2024

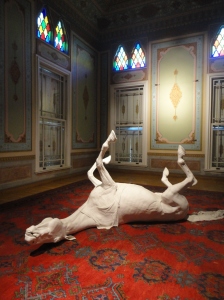

Ayşe and I visited Abdulmecid Efendi Köşkü with a friend in 2017 to see an art exhibit. Until now, my only record of that occasion may be in “Some Say Poetry,” whose first photo I took when we were walking from the kiosk down to the Bosphorus. The art, the köşk, and Telezzüz apparently all belong to the reclusive billionaire Ömer Koç, who lives in London.

Abdulmecid Efendi Köşkü and one of the artworks on display; the four photos below are from inside the kiosk on the same occasion, November 5, 2017

The website of Telezzüz gives the meaning of its name as “A deriving pleasure by the sense of taste.” That’s “A deriving,” rather than just “Deriving,” presumably because the Arabic source of telezzüz is not a participle, but a verbal noun.

More common than telezzüz is the cognate lezzet, which I remember from a televisual advertisement for M&M’s touting renkli lezzet “taste with color.” There is a phrasal verb lezzet almak, meaning literally “take pleasure.”

A definition of telezzüz that includes intellectual enjoyment is found in the New Redhouse Turkish-English Dictionary (1968). From there, as well as from the Concise Oxford Turkish Dictionary (1958), I learn the phrasal verb telezzüz etmek, meaning pretty much what lezzet almak does, though now the auxiliary verb is literally not “take,” but “make.”

What others make of pleasure is the subject of the Greek text below, constituting chapters i–iii of Book X of the Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle. What the Philosopher himself thinks will be taken up in chapters iv and v. Meanwhile, we have already had an account of pleasure in the last chapters, xi–xiv, of Book VII. To the post that took up those chapters, I gave the name “Sweetness,” because the word is cognate with the Greek word that gives us hedonism.

Nişanyan Sözlük: Çağdaş Türkçenin Etimolojisi (2018) quotes a Latin definition for telezzüz: “Voluptas, seu voluptatem percipere ex aliqua re.” Voluptas is glossed by Nişanyan as zevk and is also the name of a Roman deity, said to correspond to the Greek Hedone, although “There is no evidence that she was ever the object of cult worship,” according to Wikipedia currently; the Theoi Project quotes Socrates from Plato’s Philebus (12b): “Let us begin with the very goddess who Philebus says is spoken of as Aphrodite but is most truly named Pleasure (Ἡδονή).”

Back in the Redhouse dictionary, telezzüz felsefesi is said to be hedonism.

I seem to be a hedonist, in the sense that, for the most part, I do what I want, when I want. I may have been trained in delayed gratification, but I don’t feel as if I have had to use that training very much. Maybe this is because I have trained myself not to feel that way. I took up such considerations in “Thoreau and Anacreon” during the first spring of the Covid-19 Pandemic. I may enjoy Telezzüz the restaurant, if we should go there; however, as far as food is concerned, I get more telezzüz, the activity, from learning to make something like pizza at home, than from having it served to us by professionals.

Unfortunately the Wikipedia article on hedonism mentions neither Aristotle, who currently gets a lot of my time, nor Eudoxus, the supposed source of the theory of proportion that my Euclid group have been reading about in the Elements. Aristotle mentions Eudoxus as saying that pleasure is the good.

The Wikipedia article on Hedone does mention Aristotle, but still not Eudoxus, even though Aristotle says, in our current reading (Book X, § ii.1),

Εὔδοξος μὲν οὖν τὴν ἡδονὴν τἀγαθὸν ᾤετ᾽ εἶναι.

That pleasure is the Good was held by Eudoxus. (Rackham)

Eudoxus thought that the good is pleasure. (Apostle)

Now Eudoxus believed that pleasure is the good. (Sachs)

Now, Eudoxus thought that the good was pleasure. (Bartlett and Collins)

I suppose the translators’ disagreement over the subject of the dependent clause is due to Aristotle’s giving each of pleasure and good a definite article. Perhaps Rackham and Sachs make the better choice, because pleasure rather than goodness is what Aristotle is trying to explicate. It doesn’t really matter, if the point of Eudoxus is that pleasure and goodness are the same thing.

Obviously they are not the same thing. At least, people don’t believe they are; and if people are wrong, what is that thing, which is different from goodness, that people believe pleasure to be? That’s what I would ask, anyway.

Aristotle finishes the section already quoted by saying of Eudoxus,

ἐπιστεύοντο δ᾽ οἱ λόγοι

διὰ τὴν τοῦ ἤθους ἀρετὴν μᾶλλον

ἢ δι᾽ αὑτούς·

διαφερόντως γὰρ

ἐδόκει σώφρων εἶναι·

οὐ δὴ ὡς φίλος τῆς ἡδονῆς

ἐδόκει ταῦτα λέγειν,

ἀλλ᾽

οὕτως ἔχειν κατ᾽ ἀλήθειαν.His arguments carried conviction

more because of the virtue of his character

than on their own account,

for he seemed to be moderate

to a distinguished degree.

Indeed, he seemed to say these things,

not because he was a friend of pleasure,

but rather because he thought

that such was the case in truth.

The translation is by Bartlett and Collins, and I don’t know if it illustrates the assertion, quoted more fully below, that Aristotle “has suffered vastly by his transcribers, as all authors of great brevity necessarily must.” Bartlett and Collins do stick closely to the Greek, but not to the brevity.

That pleasure is the good: you can get away with saying and even believing that, if you have the virtue that Aristotle described in Book III, chapters vii–ix, taken up in the post that I called “Sanity.” If however you are intemperate or acratic, then believing pleasure to be automatically good can be deadly. Thus Eudoxus’s assertion may serve as an example of what Rob Henderson calls “luxury beliefs.” Says Henderson,

Luxury beliefs have, to a large extent, replaced luxury goods.

Luxury beliefs are ideas and opinions that confer status on the upper class, while often inflicting costs on the lower classes.

When people express unusual beliefs that are at odds with conventional opinion, like defunding the police or downplaying hard work, or using peculiar vocabulary, often what they are really saying is, “I was educated at a top university” or “I have the means and time to acquire these esoteric ideas.”

From Aristotle’s account, I do not infer that Eudoxus was trying to show off his social status. Possibly, like some of us, he understood his fellow humans less well than he did a technical pursuit, such as mathematics.

Robert Pirsig is like that, when he writes in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (chapter 19),

But suppose you do just what you like? Does that mean you’re going to go out and shoot heroin, rob banks and rape old ladies? The person who is counseling you not to do “just as you like” is making some remarkable presumptions as to what is likable. He seems unaware that people may not rob banks because they have considered the consequences and decided they don’t like to. He doesn’t see that banks exist in the first place because they’re “just what people like,” namely, providers of loans.

Some people do want to go out and do bad things, even things that they themselves would admit to be bad. It is true, as Pirsig says, that some of those people consider the consequences and restrain themselves. Richard Feynman acted as such a person when declining a job that came with a lot of money:

After reading the salary, I’ve decided that I must refuse. The reason I have to refuse a salary like that is I would be able to do what I’ve always wanted to do – get a wonderful mistress, put her up in an apartment, buy her nice things … With the salary you have offered, I could actually do that, and I know what would happen to me. I’d worry about her, what she’s doing; I’d get into arguments when I come home, and so on. All this bother would make me uncomfortable and unhappy. I wouldn’t be able to do physics well, and it would be a big mess! What I’ve always wanted to do would be bad for me, so I’ve decided that I can’t accept your offer.

That’s from “Surely You’re Joking, Mr Feynman!” Feynman has been trained in delayed gratification. Many people have not.

I still think Pirsig was onto something, and it is part of the reason why I continue to read his book. He continues the passage above:

Phaedrus began to wonder how all this condemnation of “what you like” ever seemed such a natural objection in the first place.

Soon he saw there was much more to this than he had been aware of. When people said, Don’t do just what you like, they didn’t just mean, Obey authority. They also meant something else.

This “something else” opened up into a huge area of classic scientific belief which stated that “what you like” is unimportant because it’s all composed of irrational emotions within yourself. He studied this argument for a long time, then knifed it into two smaller groups which he called scientific materialism and classic formalism. He said the two are often found associated in the same person but logically are separate.

Kids are told, “Don’t spend your whole allowance for bubble gum [immediate emotional impulse] because you’re going to want to spend it for something else later [big picture].” Adults are told, “This paper mill may smell awful even with the best controls [immediate emotions], but without it the economy of the whole town will collapse [big picture].” In terms of our old dichotomy, what’s being said is, “Don’t base your decisions on romantic surface appeal without considering classical underlying form.” This was something he kind of agreed with.

I must have agreed too, when I first read that in high school.

In our current reading (again, chapters i–iii of Book X of the Ethics), Aristotle makes no obvious reference to Chapter VII. Thus we are reminded that it may not have been he who assembled the ten books of the Ethics.

The editor of the Loeb Classical Library has apparently seen fit to remove, from the front matter (page vi) of the Ethics (LCL 73, Aristotle XIX), a quotation from the Letters of Thomas Gray. I pass it along here, adding the list formatting myself:

- In the first place he is the hardest author by far I ever meddled with.

- Then he has a dry conciseness that makes one imagine one is perusing a table of contents rather than a book; it tastes for all the world like chopped hay, or rather like chopped logic; for he has a violent affection to that art, being in some sort his own invention; so that he often loses himself in little trifling distinctions and verbal niceties, and what is worse, leaves you to extricate yourself as you can.

- Thirdly, he has suffered vastly by his transcribers, as all authors of great brevity necessarily must.

- Fourthly and lastly, he has abundance of fine, uncommon things, which make him well worth the pains he gives one. You see what you have to expect.

I found the quotation in a pdf file of 1956 reprint of the “New and revised edition” of 1934 (which is nominally the edition that I have on paper, but with a more recent date, 1990; this however is explicitly attached only to the Bibliography).

I went to the pdf to be able to cut and paste a passage from near the end of Rackham’s Introduction:

Among all the relics of Greek antiquity, Aristotle’s Ethics is one of those that retain their interest most freshly.

I pause after that opening sentence to note that it is an example of what I was taught in tenth-grade English: “retains” instead of “retain” would have been an error, albeit one that many people make. I took up grammar in some posts of 2018 such as “Writing Rules.” The real rules of grammar may be the ones that people actually follow; nonetheless, there may be rules of style that make for better writing when people do follow them. I took up such a rule in “Solipsism,” where the main topic is whether one really needs friends; the rule, broken by Salman Rushdie, is to avoid separating subject and object with a long parenthesis. (After the original posting, I found and added, at the end, another example of a violation of the rule.)

Rackham continues:

To many readers, new to this kind of study, its application of rigorous logical analysis to the problem of conduct comes as a revelation.

If reading Aristotle didn’t seem like a revelation to me, maybe it was because I had already seen his influence, perhaps even in Pirsig. Rackham continues:

It is true that a moral system which so exalts the life of the intellect is in many ways alien to modern thought and practice; …

I might have thought that was my moral system.

… but in so far as Aristotle’s End can be interpreted less exclusively, and taken to include complete self-development and self-expression, the full realization in healthy activity of all the potentialities of human nature, his teaching has not lost its appeal. His review of the virtues and graces of character that the Greeks admired stands in such striking contrast with Christian Ethics that this section of the work is a document of primary importance for the student of the Pagan world. But it has more than a historic value. Both in its likeness and in its difference it is a touchstone for that modern idea of a gentleman, which supplies or used to supply an important part of the English race with its working religion.

Insofar as the English “working religion” was imported to America, perhaps Pirsig rebelled against it, or perhaps against a perversion of it; see “Anthropology of Mathematics” on the “Victorians.” For now I just note that, having been listening recently to some recordings of Pirsig’s voice, I’m afraid he sounds a bit like the heir from Queens who sadly preceded Joe Biden as president of the United States.

Contents and Summary

After a break from the feature in Book IX, the roman chapters of Book X are different from the arabic ones, at least after the first.

- Chapter I = Chapter 1

- Pleasure (ἡδονή) is bound up with our kind:

- They educate the young who steer them by

- pleasure and

- pain (λύπη).

- For ethical virtue, one should

- enjoy (χαίρειν) and

- despise (μισεῖν)

what one ought, since for

- virtue (ἀρετή) and

- a happy life (εὐδαίμων βίος),

these have

- moment (ῥοπή) and

- power (δύναμις),

since [people]

- choose pleasant things

(τὰ μὲν γὰρ ἡδέα προαιροῦνται), - avoid painful things

(τὰ δὲ λυπηρὰ φεύγουσιν, § i.1).

- They educate the young who steer them by

- Different views of pleasure:

- Pleasure (ἡδονή) is bound up with our kind:

- Chapter 2

- Chapter II.

- Eudoxus, plausible because himself moderate,

said pleasure was the good, because:-

- [Pleasure] is aimed at by both

- the rational and

- the irrational.

- The desirable is the decent.

- What all are borne towards is best for all.

- This is the good (§ ii.1).

- [Pleasure] is aimed at by both

- Everybody avoids pain, and

the opposite is desirable. - What we choose

- neither on account of,

- nor for the sake of,

something else is most desirable, and

that’s pleasure. - Adding pleasure makes something more desirable, but

the good is augmented only by itself (§ ii.2):- this shows only that

pleasure is one of the goods; - Plato showed pleasure was

- made more desirable by prudence, hence

- not the good (§ ii.3).

- this shows only that

-

- Those who say the aim of all things is not the good

make no sense (μὴ οὐθὲν λέγουσιν).- We say what seems so to all.

Those who deny that belief are not more believable,- unless only the thoughtless (τὰ ἀνόητα) crave pleasure;

- how if the thoughtful (τὰ φρόνιμα) do too? –

- even in the base, some natural good may

- be better than they,

- aim at their proper good (§ ii.4).

- Pain is bad, and they say

this does not make pleasure good; however,- [pain and pleasure] are to be

- avoided, if bad;

- [treated] alike, if neither [good nor bad]; and

- that’s not what happens (§ ii.5).

- [pain and pleasure] are to be

- Pleasure is not a “suchness” or quality (ποιότης) –

but then neither are [some good things]:- the activities of virtue,

- happiness (§ iii.1).

- Pleasure is indefinite, because admitting

- more and

- less, they say,

while the good is defined.

- If they judge by

- being pleased, then

also admitting of- more and

- less

are being

- just,

- brave,

- otherwise virtuous;

- the pleasures themselves, then

they overlook the cause, namely being- unmixed or

- mixed (§ iii.2).

- being pleased, then

- Health is both

- definite and

- admitting

- more and

- less,

because the same “symmetry” (συμμετρία) does not obtain

- in all people or

- in one person at all times (§ iii.3).

- The good is complete, they say, and

pleasure is not, because it is- a moving (κίνησις) or

- a becoming (γένεσις).

However:

- Pleasure is not a motion, for

- a motion is fast or slow,

- maybe not in itself, e.g. the cosmos,

- but with respect to another, e.g.

- walking,

- growing;

- enjoying (ἥδεσθαι), i.e. the doing (ἐνεργεῖν), is not, though

- being pleased (ἡσθῆναι) may be, like

- being angered (ὀργισθῆναι, § iii.4).

- a motion is fast or slow,

- Pleasure is not a genesis, for then

- what pleasure is the genesis of,

- pain is the destruction of (§ iii.5).

- They say

- pain is a want (ἔνδεια) of something natural,

- pleasure is a filling up (ἀναπλήρωσις).

However,

- Among pleasures, there are

the most disgraceful (αἱ ἐπονειδίσται).- They are not really pleasant,

except to bad people

(as e.g. to- the sick the

- healty,

- sweet,

- bitter,

- to those with bad eyes, the white (§ iii.8).

- the sick the

- Pleasures are still desirable,

but not that way, e.g.- wealth, but not through betrayal,

- health, but not by eating certain things (§ iii.9).

- Pleasures differ in form.

- They differ,

- those from the beautiful

- from those from the shameful;

e.g. one will not enjoy

- the just without being just,

- the musical without being musical (§ iii.10).

- They are with us,

- the friend, for good, and is praised;

- the flatter, for pleasure, and is shamed (§ iii.11)

- One would not live life with a child’s

- pleasures and

- intelligence.

- One would not delight in what is

- most shameful, albeit

- not painful.

- Regardless of pleasure,

some things are desirable, e.g.- seeing,

- remembering,

- knowing,

- having virtue (§ iii.12).

- They differ,

- They are not really pleasant,

- We say what seems so to all.

- It now seems clear:

- Pleasure is not the good.

- Not every pleasure is desirable.

- Some pleasures

- are desirable in themselves, but

- differ

- in form or

- in origin (§ iii.13).

- Eudoxus, plausible because himself moderate,

Text

Book X

Chapter I

Chapter 1

§ i.1

μετὰ δὲ ταῦτα περὶ ἡδονῆς ἴσως ἕπεται διελθεῖν.

μάλιστα γὰρ δοκεῖ συνῳκειῶσθαι τῷ γένει ἡμῶν,

διὸ παιδεύουσι τοὺς νέους

οἰακίζοντες

- ἡδονῇ καὶ

- λύπῃ·

δοκεῖ δὲ καὶ πρὸς τὴν τοῦ ἤθους ἀρετὴν

μέγιστον εἶναι τὸ

- χαίρειν οἷς δεῖ καὶ

- μισεῖν ἃ δεῖ.

διατείνει γὰρ ταῦτα διὰ παντὸς τοῦ βίου,

- ῥοπὴν ἔχοντα καὶ

- δύναμιν

πρὸς

- ἀρετήν τε καὶ

- τὸν εὐδαίμονα βίον·

- τὰ μὲν γὰρ ἡδέα προαιροῦνται,

- τὰ δὲ λυπηρὰ φεύγουσιν·

§ i.2

ὑπὲρ δὲ τῶν τοιούτων ἥκιστ᾽ ἂν δόξειε παρετέον εἶναι,

- ἄλλως τε καὶ

- πολλὴν ἐχόντων ἀμφισβήτησιν.

- οἳ μὲν γὰρ τἀγαθὸν ἡδονὴν λέγουσιν,

- οἳ δ᾽ ἐξ ἐναντίας κομιδῇ φαῦλον,

- οἳ μὲν ἴσως πεπεισμένοι οὕτω καὶ ἔχειν,

- οἳ δὲ οἰόμενοι βέλτιον εἶναι

πρὸς τὸν βίον ἡμῶν

ἀποφαίνειν τὴν ἡδονὴν τῶν φαύλων,

καὶ εἰ μὴ ἐστίν·- ῥέπειν γὰρ τοὺς πολλοὺς πρὸς αὐτὴν καὶ

- δουλεύειν ταῖς ἡδοναῖς,

διὸ δεῖν εἰς τοὐναντίον ἄγειν·

ἐλθεῖν γὰρ ἂν οὕτως ἐπὶ τὸ μέσον.

§ i.3

μή ποτε δὲ οὐ καλῶς τοῦτο λέγεται.

οἱ γὰρ περὶ τῶν ἐν

- τοῖς πάθεσι καὶ

- ταῖς πράξεσι

λόγοι ἧττόν εἰσι πιστοὶ

τῶν ἔργων·

ὅταν οὖν διαφωνῶσι τοῖς κατὰ τὴν αἴσθησιν,

- καταφρονούμενοι καὶ

- τἀληθὲς προσαναιροῦσιν· [1172b]

ὁ γὰρ ψέγων τὴν ἡδονήν,

ὀφθείς ποτ᾽ ἐφιέμενος,

ἀποκλίνειν δοκεῖ πρὸς αὐτὴν ὡς τοιαύτην οὖσαν ἅπασαν·

τὸ διορίζειν γὰρ οὐκ ἔστι τῶν πολλῶν.

§ i.4

ἐοίκασιν οὖν οἱ ἀληθεῖς τῶν λόγων

- οὐ μόνον πρὸς τὸ εἰδέναι

χρησιμώτατοι εἶναι, - ἀλλὰ καὶ πρὸς τὸν βίον·

συνῳδοὶ γὰρ ὄντες τοῖς ἔργοις πιστεύονται,

διὸ προτρέπονται τοὺς συνιέντας ζῆν κατ᾽ αὐτούς.

- τῶν μὲν οὖν τοιούτων ἅλις·

- τὰ δ᾽ εἰρημένα περὶ τῆς ἡδονῆς ἐπέλθωμεν.

Chapter II

Chapter 2

§ ii.1

Εὔδοξος μὲν οὖν τὴν ἡδονὴν τἀγαθὸν ᾤετ᾽ εἶναι

διὰ

-

τὸ πάνθ᾽ ὁρᾶν ἐφιέμενα αὐτῆς,

- καὶ ἔλλογα

- καὶ ἄλογα,

-

ἐν πᾶσι δ᾽ εἶναι

- τὸ αἱρετὸν τὸ ἐπιεικές, καὶ

- τὸ μάλιστα κράτιστον·

-

τὸ δὴ πάντ᾽ ἐπὶ ταὐτὸ φέρεσθαι μηνύειν

ὡς πᾶσι τοῦτο ἄριστον ὄν

(ἕκαστον γὰρ τὸ αὑτῷ ἀγαθὸν εὑρίσκειν,

ὥσπερ καὶ τροφήν), -

- τὸ δὲ πᾶσιν ἀγαθόν, καὶ

- οὗ πάντ᾽ ἐφίεται,

τἀγαθὸν εἶναι.

ἐπιστεύοντο δ᾽ οἱ λόγοι

- διὰ τὴν τοῦ ἤθους ἀρετὴν μᾶλλον

- ἢ δι᾽ αὑτούς·

διαφερόντως γὰρ ἐδόκει σώφρων εἶναι·

- οὐ δὴ ὡς φίλος τῆς ἡδονῆς ἐδόκει ταῦτα λέγειν,

- ἀλλ᾽ οὕτως ἔχειν κατ᾽ ἀλήθειαν.

§ ii.2

οὐχ ἧττον δ᾽ ᾤετ᾽ εἶναι φανερὸν ἐκ τοῦ ἐναντίου·

τὴν γὰρ λύπην καθ᾽ αὑτὸ πᾶσι φευκτὸν εἶναι,

ὁμοίως δὴ τοὐναντίον αἱρετόν·

μάλιστα δ᾽ εἶναι αἱρετὸν ὃ

- μὴ δι᾽ ἕτερον

- μηδ᾽ ἑτέρου χάριν

αἱρούμεθα·

τοιοῦτο δ᾽ ὁμολογουμένως εἶναι τὴν ἡδονήν·

οὐδένα γὰρ ἐπερωτᾶν τίνος ἕνεκα ἥδεται,

ὡς καθ᾽ αὑτὴν οὖσαν αἱρετὴν τὴν ἡδονήν.

προστιθεμένην τε ὁτῳοῦν τῶν ἀγαθῶν αἱρετώτερον ποιεῖν,

οἷον τῷ δικαιοπραγεῖν καὶ σωφρονεῖν,

αὔξεσθαι δὲ τὸ ἀγαθὸν αὑτῷ.

§ ii.3

ἔοικε δὴ οὗτός γε ὁ λόγος

- τῶν ἀγαθῶν αὐτὴν ἀποφαίνειν, καὶ

- οὐδὲν μᾶλλον ἑτέρου·

πᾶν γὰρ μεθ᾽ ἑτέρου ἀγαθοῦ

- αἱρετώτερον

- ἢ μονούμενον.

τοιούτῳ δὴ λόγῳ καὶ Πλάτων ἀναιρεῖ ὅτι οὐκ ἔστιν ἡδονὴ τἀγαθόν·

- αἱρετώτερον γὰρ εἶναι τὸν ἡδὺν βίον μετὰ φρονήσεως

- ἢ χωρίς,

εἰ δὲ τὸ μικτὸν κρεῖττον,

οὐκ εἶναι τὴν ἡδονὴν τἀγαθόν·

οὐδενὸς γὰρ προστεθέντος αὐτῷ

τἀγαθὸν αἱρετώτερον γίνεσθαι.

δῆλον δ᾽ ὡς οὐδ᾽ ἄλλο οὐδὲν τἀγαθὸν ἂν εἴη,

ὃ μετά τινος τῶν καθ᾽ αὑτὸ ἀγαθῶν

αἱρετώτερον γίνεται.

§ ii.4

τί οὖν ἐστὶ τοιοῦτον, οὗ καὶ ἡμεῖς κοινωνοῦμεν;

τοιοῦτον γὰρ ἐπιζητεῖται.

οἱ δ᾽ ἐνιστάμενοι ὡς οὐκ ἀγαθὸν οὗ πάντ᾽ ἐφίεται, μὴ οὐθὲν λέγουσιν. [1173a]

ἃ γὰρ πᾶσι δοκεῖ, ταῦτ᾽ εἶναί φαμεν·

ὁ δ᾽ ἀναιρῶν ταύτην τὴν πίστιν οὐ πάνυ πιστότερα ἐρεῖ.

- εἰ μὲν γὰρ τὰ ἀνόητα ὀρέγεται αὐτῶν,

ἦν ἄν τι λεγόμενον, - εἰ δὲ καὶ τὰ φρόνιμα,

πῶς λέγοιεν ἄν τι; - ἴσως δὲ καὶ ἐν τοῖς φαύλοις ἔστι τι φυσικὸν ἀγαθὸν

- κρεῖττον ἢ καθ᾽ αὑτά,

- ὃ ἐφίεται τοῦ οἰκείου ἀγαθοῦ.

§ ii.5

οὐκ ἔοικε δὲ οὐδὲ περὶ τοῦ ἐναντίου καλῶς λέγεσθαι.

οὐ γάρ φασιν,

- εἰ ἡ λύπη κακόν ἐστι,

- τὴν ἡδονὴν ἀγαθὸν εἶναι·

ἀντικεῖσθαι γὰρ

- καὶ κακὸν κακῷ

- καὶ ἄμφω τῷ μηδετέρῳ –

λέγοντες ταῦτα οὐ κακῶς,

οὐ μὴν ἐπί γε τῶν εἰρημένων ἀληθεύοντες.

ἀμφοῖν γὰρ ὄντοιν

- τῶν κακῶν καὶ φευκτὰ ἔδει ἄμφω εἶναι,

- τῶν μηδετέρων δὲ μηδέτερον ἢ ὁμοίως·

νῦν δὲ φαίνονται

- τὴν μὲν φεύγοντες ὡς κακόν,

- τὴν δ᾽ αἱρούμενοι ὡς ἀγαθόν·

οὕτω δὴ καὶ ἀντίκειται.

Chapter III

§ iii.1

οὐ μὴν οὐδ᾽

- εἰ μὴ τῶν ποιοτήτων ἐστὶν ἡ ἡδονή,

- διὰ τοῦτ᾽ οὐδὲ τῶν ἀγαθῶν·

- οὐδὲ γὰρ αἱ τῆς ἀρετῆς ἐνέργειαι ποιότητές εἰσιν,

- οὐδ᾽ ἡ εὐδαιμονία.

§ iii.2

λέγουσι δὲ

- τὸ μὲν ἀγαθὸν ὡρίσθαι,

- τὴν δ᾽ ἡδονὴν ἀόριστον εἶναι,

ὅτι δέχεται- τὸ μᾶλλον καὶ

- τὸ ἧττον.

- εἰ μὲν οὖν ἐκ τοῦ ἥδεσθαι τοῦτο κρίνουσι,

καὶ περὶ- τὴν δικαιοσύνην καὶ

- τὰς ἄλλας ἀρετάς,

καθ᾽ ἃς ἐναργῶς φασὶ

- μᾶλλον καὶ

- ἧττον

τοὺς ποιοὺς

- ὑπάρχειν καὶ

- πράττειν

κατὰ τὰς ἀρετάς, ἔσται ταὐτά·

-

- δίκαιοι γάρ εἰσι μᾶλλον καὶ

- ἀνδρεῖοι,

- ἔστι δὲ καὶ

- δικαιοπραγεῖν καὶ

- σωφρονεῖν

- μᾶλλον καὶ

- ἧττον.

- εἰ δὲ ταῖς ἡδοναῖς,

μή ποτ᾽ οὐ λέγουσι τὸ αἴτιον, ἂν ὦσιν- αἳ μὲν ἀμιγεῖς

- αἳ δὲ μικταί.

§ iii.3

καὶ τί κωλύει,

- καθάπερ ὑγίεια

ὡρισμένη οὖσα

δέχεται- τὸ μᾶλλον καὶ

- τὸ ἧττον,

- οὕτω καὶ τὴν ἡδονήν;

- οὐ γὰρ ἡ αὐτὴ συμμετρία ἐν πᾶσίν ἐστιν,

- οὐδ᾽ ἐν τῷ αὐτῷ μία τις ἀεί,

- ἀλλ᾽ ἀνιεμένη

- διαμένει ἕως τινός, καὶ

- διαφέρει τῷ

- μᾶλλον καὶ

- ἧττον.

τοιοῦτον δὴ καὶ τὸ περὶ τὴν ἡδονὴν ἐνδέχεται εἶναι.

§ iii.4

- τέλειόν τε τἀγαθὸν τιθέντες,

-

- τὰς δὲ κινήσεις καὶ

- τὰς γενέσεις

ἀτελεῖς,

τὴν ἡδονὴν

- κίνησιν καὶ

- γένεσιν

ἀποφαίνειν πειρῶνται.

οὐ καλῶς δ᾽ ἐοίκασι λέγειν

οὐδ᾽ εἶναι κίνησιν.

πάσῃ γὰρ οἰκεῖον εἶναι δοκεῖ

- τάχος καὶ

- βραδυτής,

καὶ

- εἰ μὴ καθ᾽ αὑτήν, οἷον τῇ τοῦ κόσμου,

- πρὸς ἄλλο·

τῇ δ᾽ ἡδονῇ τούτων οὐδέτερον ὑπάρχει.

- ἡσθῆναι μὲν γὰρ ἔστι ταχέως

- ὥσπερ ὀργισθῆναι, [1173b]

- ἥδεσθαι δ᾽ οὔ,

- οὐδὲ πρὸς ἕτερον,

- βαδίζειν δὲ καὶ αὔξεσθαι καὶ πάντα τὰ τοιαῦτα.

- μεταβάλλειν μὲν οὖν εἰς τὴν ἡδονὴν

- ταχέως καὶ

- βραδέως

ἔστιν,

- ἐνεργεῖν δὲ κατ᾽ αὐτὴν οὐκ ἔστι ταχέως,

- λέγω δ᾽ ἥδεσθαι.

Bywater has this with no comma; Rackham inserts one after λέγειν:

οὐ καλῶς δ᾽ ἐοίκασι λέγειν οὐδ᾽ εἶναι κίνησιν.

§ iii.5

γένεσίς τε πῶς ἂν εἴη;

δοκεῖ γὰρ

- οὐκ

- ἐκ τοῦ τυχόντος

- τὸ τυχὸν γίνεσθαι,

- ἀλλ᾽

- ἐξ οὗ γίνεται,

- εἰς τοῦτο διαλύεσθαι·

καὶ

- οὗ γένεσις ἡ ἡδονή,

- τούτου ἡ λύπη φθορά.

§ iii.6

καὶ λέγουσι δὲ

- τὴν μὲν λύπην ἔνδειαν τοῦ κατὰ φύσιν εἶναι,

- τὴν δ᾽ ἡδονὴν ἀναπλήρωσιν.

ταῦτα δὲ σωματικά ἐστι τὰ πάθη.

εἰ δή ἐστι τοῦ κατὰ φύσιν ἀναπλήρωσις ἡ ἡδονή,

- ἐν ᾧ ἡ ἀναπλήρωσις,

- τοῦτ᾽ ἂν καὶ ἥδοιτο·

τὸ σῶμα ἄρα·

οὐ δοκεῖ δέ·

- οὐδ᾽ ἔστιν ἄρα ἡ ἀναπλήρωσις ἡδονή,

- ἀλλὰ

- γινομένης μὲν ἀναπληρώσεως ἥδοιτ᾽ ἄν τις,

- καὶ †τεμνόμενος† λυποῖτο.

ἡ δόξα δ᾽ αὕτη δοκεῖ γεγενῆσθαι ἐκ τῶν περὶ τὴν τροφὴν

- λυπῶν καὶ

- ἡδονῶν·

- ἐνδεεῖς γὰρ γενομένους καὶ προλυπηθέντας

- ἥδεσθαι τῇ ἀναπληρώσει.

§ iii.7

τοῦτο δ᾽ οὐ περὶ πάσας συμβαίνει τὰς ἡδονάς·

ἄλυποι γάρ εἰσιν

- αἵ τε μαθηματικαὶ καὶ

- τῶν κατὰ τὰς αἰσθήσεις

- αἱ διὰ τῆς ὀσφρήσεως,

- καὶ

- ἀκροάματα δὲ καὶ

- ὁράματα πολλὰ καὶ

- μνῆμαι καὶ

- ἐλπίδες.

τίνος οὖν αὗται γενέσεις ἔσονται;

οὐδενὸς γὰρ ἔνδεια γεγένηται,

οὗ γένοιτ᾽ ἂν ἀναπλήρωσις.

§ iii.8

πρὸς δὲ τοὺς προφέροντας τὰς ἐπονειδίστους τῶν ἡδονῶν

λέγοι τις ἂν ὅτι οὐκ ἔστι ταῦθ᾽ ἡδέα

(οὐ γὰρ

εἰ τοῖς κακῶς διακειμένοις ἡδέα ἐστίν,

οἰητέον αὐτὰ καὶ ἡδέα εἶναι πλὴν τούτοις,

καθάπερ

- οὐδὲ τὰ τοῖς κάμνουσιν

- ὑγιεινὰ ἢ

- γλυκέα ἢ

- πικρά,

- οὐδ᾽ αὖ λευκὰ τὰ φαινόμενα τοῖς ὀφθαλμιῶσιν)·

§ iii.9

ἢ οὕτω λέγοι τις ἄν, ὅτι

αἱ μὲν ἡδοναὶ αἱρεταί εἰσιν,

οὐ μὴν ἀπό γε τούτων,

ὥσπερ

- καὶ τὸ πλουτεῖν, προδόντι δ᾽ οὔ,

- καὶ τὸ ὑγιαίνειν, οὐ μὴν ὁτιοῦν φαγόντι·

§ iii.10

ἢ τῷ εἴδει διαφέρουσιν αἱ ἡδοναί·

ἕτεραι γὰρ

- αἱ ἀπὸ τῶν καλῶν

- τῶν ἀπὸ τῶν αἰσχρῶν,

καὶ

- οὐκ ἔστιν ἡσθῆναι τὴν τοῦ δικαίου

μὴ ὄντα δίκαιον - οὐδὲ τὴν τοῦ μουσικοῦ

μὴ ὄντα μουσικόν, - ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ ἐπὶ τῶν ἄλλων.

§ iii.11

ἐμφανίζειν δὲ δοκεῖ καὶ

ὁ φίλος ἕτερος ὢν τοῦ κόλακος

- οὐκ οὖσαν ἀγαθὸν τὴν ἡδονὴν ἢ

- διαφόρους εἴδει·

- ὃ μὲν γὰρ πρὸς τἀγαθὸν ὁμιλεῖν δοκεῖ,

- ὃ δὲ πρὸς ἡδονήν,

καὶ

- τῷ μὲν ὀνειδίζεται,

- τὸν δ᾽ ἐπαινοῦσιν

ὡς πρὸς ἕτερα ὁμιλοῦντα. [1174a]

§ iii.12

-

οὐδείς τ᾽ ἂν ἕλοιτο ζῆν παιδίου διάνοιαν ἔχων διὰ βίου,

ἡδόμενος ἐφ᾽ οἷς τὰ παιδία ὡς οἷόν τε μάλιστα, -

οὐδὲ χαίρειν ποιῶν τι τῶν αἰσχίστων,

μηδέποτε μέλλων λυπηθῆναι. -

περὶ πολλά τε σπουδὴν ποιησαίμεθ᾽ ἂν

καὶ εἰ μηδεμίαν ἐπιφέροι ἡδονήν,οἷον

- ὁρᾶν,

- μνημονεύειν,

- εἰδέναι,

- τὰς ἀρετὰς ἔχειν.

εἰ δ᾽ ἐξ ἀνάγκης ἕπονται τούτοις ἡδοναί,

οὐδὲν διαφέρει·ἑλοίμεθα γὰρ ἂν ταῦτα

καὶ εἰ μὴ γίνοιτ᾽ ἀπ᾽ αὐτῶν ἡδονή.

§ iii.13

- ὅτι μὲν οὖν

- οὔτε τἀγαθὸν ἡ ἡδονὴ

- οὔτε πᾶσα αἱρετή,

δῆλον ἔοικεν εἶναι, καὶ

- ὅτι εἰσί τινες

- αἱρεταὶ καθ᾽ αὑτὰς

- διαφέρουσαι

- τῷ εἴδει ἢ

- ἀφ᾽ ὧν.

τὰ μὲν οὖν λεγόμενα περὶ τῆς

- ἡδονῆς καὶ

- λύπης

ἱκανῶς εἰρήσθω.

Edited May 28, 2024

One Trackback

[…] « Hedonism […]