This reviews some reading and thinking of recent weeks, pertaining more or less to the title subjects, of which it may be worth noting that

- poetry is from ποιέω “make”;

- mathematics is from μανθάνω “learn.”

Summary added August 23, 2020: Mathematics may bring out such emotions as poetry does; but in the ideal, a work of mathematics is correct or not, in a sense that everybody will agree on. Here I review work of

- Lisa Morrow, writing in Meanjin as an immigrant to Istanbul, like me.

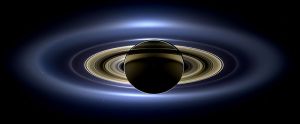

- Wendell Berry, in “The Peace of Wild Things,” which things “do not tax their lives with forethought / of grief,” and include the stars.

- Randall Jarrell, in The Animal Family.

- Mary Midgley, in Evolution as a Religion, on how we see animals.

- James Beall, astronomer, poet of the stars, tutor at my college.

- Edith Södergran, in “God,” as translated by Nicholas Lawrence in Cordite.

- Lukas Moodysson, in Fucking Åmål, where Agnes’s father notices that his daughter is reading Edith Södergran.

- Thomas J.J. Altizer, in The Gospel of Christian Atheism, a book that I kept from my father’s collection.

- Özge Samancı, in Dare to Disappoint, where the character to be disappointed is the father of the artist, and where Özlem (the artist’s friend and mine) praises the poetry of mathematics.

- Fiona Hile, writing, quâ editor of an issue of Cordite featuring poetry of mathematics, about the set theory of Maryanthe Malliaris and Saharon Shelah.

- Anupama Pilbrow, a poet writing in Meanjin about studying mathematics.

- Robert Pirsig, about students who ask their teacher, “Is this what you want?”

- R. G. Collingwood, who in Speculum Mentis analyzes Art, Religion, Science, History, and Philosophy as modes of existence.

- Michael Oakeshott, supposedly influenced by Collingwood, but also considered a forefather of “postmodern conservatism,” and analyzing existence into different modes from Collingwood’s, the latter according to the article in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy by Terry Nardin, who reports, “to insist on the primacy of any single mode is not only boorish but barbaric.”

- Allan Bloom, who suggests, in The Closing of the American Mind, that for Ronald Reagan, for the Soviet Union to be “the evil empire” and to “have different values” from the United States is the same thing.

- Galen Strawson, who seems to belie the possibility of different modes of being by saying, “we know exactly what consciousness is,” and also, “The nature of physical stuff is mysterious except insofar as consciousness is itself a form of physical stuff,” when (according to me) consciousness is simply not physical, not in the sense of being studied by physics.

A Twitter friend living here in Istanbul announced (on June 16) her pleasure in having a memoir published in Meanjin.